Thomas Edison and the Cult of Sleep Deprivation

The man who gave us the incandescent light bulb thought we should never turn out the lights at all.

The March/April issue of Bethesda Magazine, a regional publication that covers a wealthy area of Washington, D.C., drew some unusually heavy attention on the web for a profile of Melissa “Missy” Lesmes, “a veritable supermom.”

“A fit, petite, vivacious blonde, Missy is at age 46 a wife, a mother of four kids ranging in age from 11 to 18 and all in separate schools, a partner at a prestigious Washington, D.C. law firm ... a party maven always up for a gathering at her Chevy Chase home, a longtime friend to women who profess she’s always there when they need her, and a woman who still manages to give back to the community.”

She's super, Q.E.D.

The title of the piece was “We Don’t Know How She Does It.” But how she does indeed do it became clear when the magazine described Lesmes’ daily schedule:

“Missy rises at 5:30 a.m. to run on the Capital Crescent Trail or head downtown to work out with a personal trainer. She’s back home by 7 to make sure the kids are awake and getting ready for school.

... “Arrives at her spacious office by 8:30 or so”

... “gets home between 7:30 and 8”

Then: dinner, which the couple eats standing up, homework help, and climbing into bed at “10 or 10:30”—to finish a brief. Lights out at midnight.

As the definition of modern success inflates, one way Lesmes and other high-achievers accomplish the impossible is by cutting back on sleep.

For some, sleep loss is a badge of honor, a sign that they don’t require the eight-hour biological reset that the rest of us softies do. Others feel that keeping up with peers requires sacrifice at the personal level—and at least in the short-term, sleep is an invisible sacrifice.

The problem has accelerated with our hyper-connected lives, but it isn't new. Purposeful sleep deprivation originates from the lives and adages of some of America's early business tycoons.

Lesmes told Bethesda Magazine she worked her way through high school and college. “That was the point I realized I wanted to keep busy,” she said. And “once I started down that road, I started to realize I like having [money], so that motivated me a lot as well.”

Still, she feels inadequate: “I can’t be the perfect mom. I want to be, but there’s just not enough time, not enough hours.”

***

You don’t need Arianna Huffington to tell you that most adults should sleep seven to nine hours per night, but they don’t. A 2010 CDC survey of more than 15,000 adults found that 30 percent of workers sleep six or fewer hours a day. And although sleep deprivation is particularly common among those who work graveyard shifts, traditional, but long, working hours can also be a problem. A 2009 study of British civil servants found that those who worked more than 55 hours a week, compared with 35 to 40 hours, were nearly twice as likely to be short on sleep.

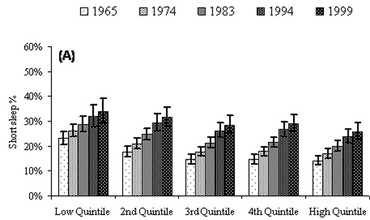

Sleep loss is most common among older workers (ages 30 to 64), and among those who earn little and work multiple jobs. Still, about a quarter of people in the top income quintile report regularly being short on sleep, and sleep deprivation across all income groups has been rising over the years. A group of sleep researchers recently told the BBC that people are now getting one or two hours less shut-eye each night than they did 60 years ago, primarily because of the encroachment of work into downtime and the proliferation of blue-light emitting electronics.

"We are the supremely arrogant species; we feel we can abandon four billion years of evolution and ignore the fact that we have evolved under a light-dark cycle,” Oxford University Professor Russell Foster said. "And long-term, acting against the clock can lead to serious health problems."

These problems include well-documented correlations with heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and accidents. A March study published in the Journal of Neuroscience found that long-term sleep loss was associated with permanent brain damage in rats.

***

Some people stay awake because they can’t or don’t want to sleep—they have insomnia, or their Netflix queues beckon. But surveys suggest that at least for some workers, sleep is the first thing to go when there’s pressure to get more done. A quarter of Americans say that their current workday or routine doesn’t allow them to get as much sleep as they’d like.

Indeed, profiles of the rich and productive are riddled with humble-braggy quotes about how little they rest. Yahoo’s Marissa Mayer reportedly sleeps just four to six hours per night. She makes up for it, she says, “by taking week-long vacations every four months.”

MSNBC’s Willie Geist, former host of the 5:30 a.m. show “Way Too Early,” used a psychological trick to fool himself into thinking he was well-rested, even on no sleep: “If you catch your body at a weak moment, as I often do, it might actually believe you when you tell it after four hours of sleep that you actually slept a full night and you feel like a million bucks.”

Jack Dorsey, founder of both Square and Twitter, once said he spends up to 10 hours a day at each company. The remaining four, presumably, are for sleep and whatever else.

Years ago I covered start-ups, and rarely did an interview with an entrepreneur not include some mention of 3 a.m. coding sprees (followed by 8 a.m. VC pitch meetings, natch). One man told me he stayed up till the wee hours reading trade publications about retail—the industry he was intent on “disrupting.”

As if it weren’t enough that our devices, our kids, and our schedules keep us up, certain white-collar sectors seem to demand this type of sleepless hyper-performance. “Our consumption-oriented economy profits more when people are awake longer,” Charles Czeisler, head of the Division of Sleep Medicine at Harvard Medical School, told the Boston Globe.

An unusually pithy Donald Trump might have summed up the rich man’s sleep conundrum best: “How does somebody that's sleeping 12 and 14 hours a day compete with someone that's sleeping three or four?"

So it’s perhaps no surprise to learn that the idea of "manly wakefulness," as Penn State labor history professor Alan Derickson describes it, also has its roots in the life of a famous entrepreneur.

***

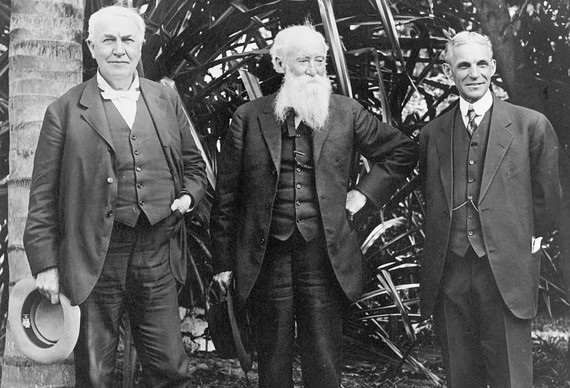

It’s fitting that Thomas Edison, the father of artificial light, was also a staunch opponent of sleep. As Derickson writes in his book Dangerously Sleepy: Overworked Americans and the Cult of Manly Wakefulness, “Edison spent considerable amounts of his own and his staff’s energy on in publicizing the idea that success depended in no small part in staying awake to stay ahead of the technological and economic competition.”

No one, Derickson argues, “did more to frame the issue as a simple choice between productive work and unproductive rest.”

Early newspaper accounts touted Edison’s willingness to work “at all hours, night or day,” to frequently rack up more than a hundred hours of work in a week, and his tendency to select his subordinates based largely on their physical endurance.

In an 1889 interview with Scientific American, Edison claimed he slept no more than four hours a day, and he apparently enforced the same vigilance among his employees.

“At first the boys had some difficulty in keeping awake, and would go to sleep under stairways and in corners,” Edison said. “We employed watchers to bring them out, and in time they got used to it.”

Edison’s assistants were “expected to keep pace with him,” John Hubert Greusel wrote in 1913. “When they fell from sheer exhaustion he seemed to begrudge the brief hours they were sleeping.”

Over time, children’s books and magazines began to promote this type of Edisonian asceticism. “One juvenile motivational text featured a photo of Edison with a group of workers identified as his Insomnia Squad,” Derickson writes. Early 20th century biographies of Edison featured him interviewing job candidates at 4 a.m. and cat-napping on lab benches between marathon work sessions.

Some short-sleepers might have shrugged and said they were simply biologically lucky. But Edison encouraged all Americans to follow his lead, claiming that sleeping eight hours a night was a waste and even harmful.

“There is really no reason why men should go to bed at all,” he said in 1914.

As Edison hero-worship hit its peak, Charles Lindbergh flew across the Atlantic in 1927, a feat that required him to remain alert and piloting for 33 hours straight. When he landed, he claimed he had experienced “no trouble keeping awake.”

Early psychologists, such as Colgate University’s Donald Laird, relied on celebrity examples like Edison and Lindbergh to make the case that less sleep was more. (At one point, Laird argued that “99 percent of cases of sleeplessness are a blessing,” Derickson wrote.)

Self-help gurus ran with the message from there. “We don’t even know if we have to sleep at all!” chirped Dale Carnegie in How to Stop Worrying and Start Living.

The enthusiasm for insomnia didn’t taper until the booming late 1950s, when few felt the need to go without, including without sleep. But sleeplessness ramped up again with the uber-competitive economy of the late 1970s and 80s.

“From the end of the second World War to the mid-70s, America is riding high and people could lead a more reasonable life,” Derickson told me in an interview. “But the party ends in the mid-70s. You have the oil shock, the rise of the Japanese economy, and an upturn in globalization. America starts freaking out.”

In Derickson’s estimation, our sleep-deprived mania has only worsened since then. He quotes The Accidental Billionaires, Ben Mezrich’s Facebook creation story, as evidence:

“Eduardo [Saverin] was pretty sure Mark hadn’t slept much in the past week,” Mezrich writes. “He had been working round the clock, light to dark to light.”