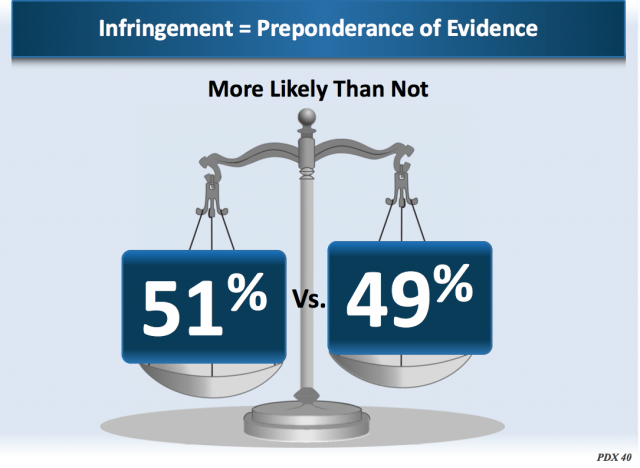

Vringo is a little company that's made a huge bet on suing Google over patents. Today that bet paid off, although to a much lesser degree than its investors hoped earlier. After a two-week trial in Virginia, a jury found that Google's advertising system infringes two old Lycos patents purchased by Vringo in 2011, and that those patents are valid.

Google and several of its advertising partners were ordered to pay a total of about $30 million. That's a lot of money, but far less than the $493 million Vringo was seeking. According to a report just published in the Virginian-Pilot, the jury found that Google will have to pay $15.9 million. Its advertising partners must pay smaller amounts: $7.9 million in damages for AOL, $6.6 million for IAC Search & Media, $98,800 for Target, and $4,000 for Gannett. The jury also said Google should pay an ongoing royalty; but whether that ultimately sticks is up to the judge.

The Vringo case is remarkable for two reasons: first, it's rare to see a high-profile patent attack played out directly in the stock market, with investors speculating on each move in court. Second, demonstratives submitted in Vringo's case show a fascinating story in pictures of how a company that's more or less a "patent troll" tries to convince a jury to shower it with money. Some of those visuals are posted below.

Aside from patents, there isn't much to Vringo's business. That's why its stock price has been so reactive to court developments. It has a "video ringtone" operation with thousands of customers, mostly abroad. That has seen little success, though, and Vringo has hemorrhaged cash for years. In a last-ditch shot at success, Vringo bought two patents, Nos. 6,314,420 and 6,775,664, that originated at Lycos, an early search competitor. It set those patents up in a shell company called I/P Engine and sued Google last year.

Vringo quickly got a high profile. Investors like Mark Cuban helped, as did some loud articles in the tech press. That particular piece, written by Vringo investor James Altucher, was headlined "Why Google Might Be Going to $0." Altucher pumped up Andrew Lang, the inventor on the Lycos/Vringo patents, and suggested they could be worth $80 million.

The jury certainly didn't agree with that analysis. However, Vringo is now in a position to go after other websites that use Google advertisements. Since the beginning of the trial, Vringo stock (NYSE:VRNG) has shot up, then plummeted, and jumped back again. Trading was halted this morning for a few hours following the verdict. It's now resumed and is hovering around $3.60 per share, slightly below where it was before the verdict.

Winning the Case: The Constitution, SmartASS, and the 51%

Several demonstratives used in court have been submitted into evidence. Combined with courthouse accounts, the pictures weave a fascinating, though partial, picture of how Vringo is made its case to the jury. These slides were presented during Vringo's opening arguments and various expert witness testimony. Google has objected to all of them (which is why they are in the public record.)

First of all, they let the jury know where patents come from—why, the Constitution, of course! It was none other than the founding fathers, pictured in this slide, who wanted patents to flourish on a new continent. Vringo showed this one-off during opening statements.

(Side note: Is it just me, or does the picture showing off the "IP Clause" of the Constitution look like it's carved in a stone tablet?)

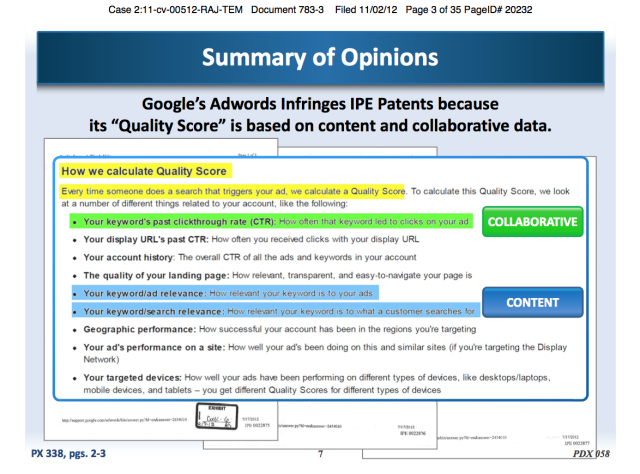

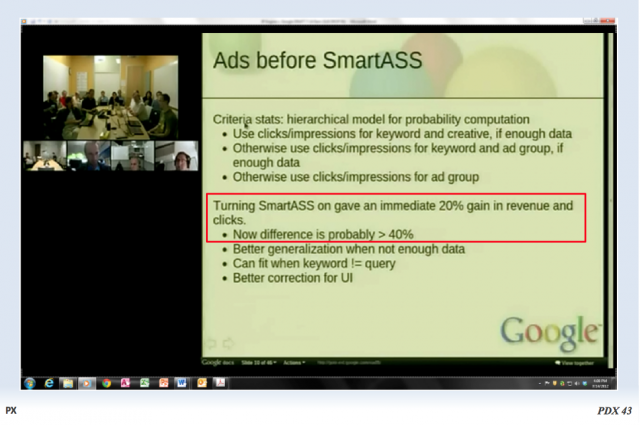

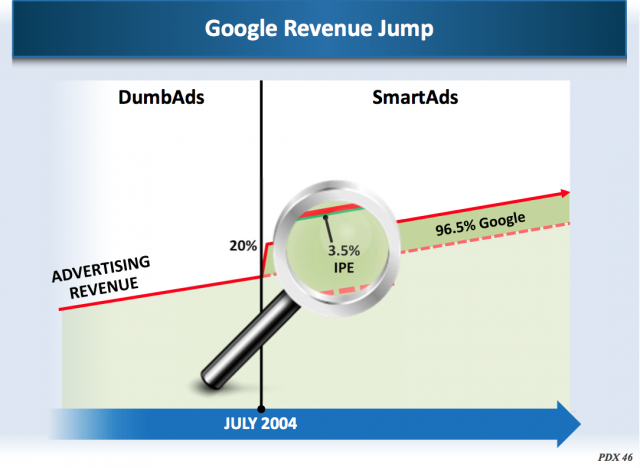

The patents describe using a combination of "content" and "collaboration" to produce better ads online. The plaintiff says Google's system of advertising, called SmartASS (for SmartAdServingSystem), infringes those patents.

The "content" side of the technology basically means picking ads relevant to a search term; the "collaboration" side means things like measuring how many users actually click on the ads. Google uses that as part of its algorithm-driven auction that instantly determines ad placement. This slide shows how Vringo believes Google is using its patented system.

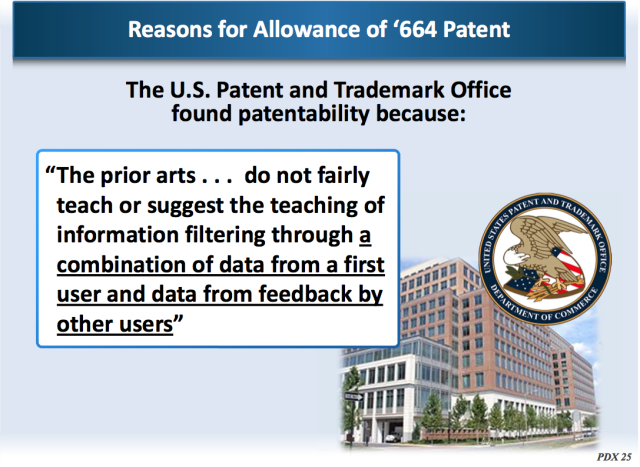

It had never been done before, argued Vringo lawyers. Examiners carefully reviewed those Vringo patents, saw the prior art, and granted away, as shown in the above slide. Google's lawyers displayed additional prior art during trial, but the jury was obviously unconvinced.

Vringo's payday curtailed by judge's mid-trial order

Soon Vringo stock will resume trading, and we'll see how the market reacts to this patent win. Some starry-eyed investors believed that Google might end up paying out $1 billion or more, combining the $493 million damage demand laid out at opening with the ongoing royalty they believed would be tacked on to that sum.

That obviously isn't going to happen. In the middle of trial, US District Judge Raymond Jackson issued a ruling that foreclosed the most heated of those billion-dollar dreams, putting a strict cap on Vringo's ultimate payday. He limited the company to receiving damages only from the day it had filed the lawsuit in 2011. Originally, Vringo had wanted damages back to 2005. The stock price hit a nadir of $1.91 per share on the afternoon of October 31, shortly after Jackson's ruling. (It rebounded to around $4 per share after the jury deliberations dragged on to a third day.)

reader comments

40