If you spend enough time in the tech industry, certain cultural touchstones become familiar. The sprawling virtual metaverse of Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, for instance, which was required reading for new product managers at Facebook, or the voice-activated computers of Star Trek, now referenced in a hidden “Easter egg” feature in Amazon’s Echo smart speakers.

But Evan Spiegel is talking about art. As the 27-year-old founder and chief executive of Snap Inc – née Snapchat, after the company’s main product – references Damien Hirst’s latest exhibition in Venice, Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, it becomes clear that Spiegel isn’t like other founders.

The exhibition saw Hirst filling the Palazzo Grassi with treasures recovered from the ancient ship Apistos, which was wrecked in the Mediterranean. A documentary at the museum chronicled the task of raising the monuments from the seafloor, where they had lain for thousands of years. Of course, the Apistos never existed and the enormous statues were created by the artist himself. “Venice is already so unbelievable, this city on the water, that all of the art that he has created is completely believable,” Spiegel says. “You’re there, walking through these exhibits, and it feels real. Like, completely real.”

It’s clear why the show connected with him. Snapchat was initially best known for its disappearing messages, gaining it a reputation as the “sexting” app. But if it has one standout feature in 2017, it’s the app’s reality-warping lenses. Tap one button and pores are smoothed over, eyes enlarged and cheekbones sharpened; tap another and a dog’s nose and ears are superimposed on your face; tap a third and a dancing hotdog appears in your living room. “I think art has always played with this concept of reality,” Spiegel says, “and so I think it’s very exciting now that technology is playing a much bigger role in art.”

He sounds sincere. It’s another reminder of how Spiegel and Snap stand apart from the wider industry, literally – the company is based not in Silicon Valley, but 300 miles south, in Los Angeles’ Venice Beach – and philosophically.

In many ways, Spiegel’s background conforms to the stereotype of the modern startup founder. Born and raised in Pacific Palisades, a ritzy neighbourhood just north of Snap’s Los Angeles headquarters, the son of two lawyers, he had a comfortable upbringing. An expensive private school led to Stanford University, where he majored in product design and acted as the social chair of the Kappa Sigma fraternity. (When some compromising emails from his time in that role surfaced in 2014, Spiegel apologised, saying: “I’m sorry I wrote them at the time and I was a jerk to have written them. They in no way reflect who I am today or my views towards women.”)

It was in Kappa Sigma that he met Bobby Murphy, Snapchat’s co-founder and current CTO, who wrote the code for the initial version of the app, and Reggie Brown, who sued the pair in 2013, alleging that the original idea of messages that were deleted after they had been viewed was his. Brown received a $158m settlement in 2014 and Spiegel said at the time that “we acknowledge Reggie’s contribution to the creation of Snapchat and appreciate his work in getting the application off the ground”.

Like Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates before him, Spiegel dropped out of university before graduating to work full-time on the app, when it was called Picaboo. Its early growth was incredibly fast; although stereotyped as a sexting app, it tapped in to people’s fears of leaving an eternal digital trail. You didn’t have to put on your makeup for Snapchat or even brush your hair. The pic would be gone seconds later. That allowed its users to approach picture messaging with the same casual freedom that they did texting. Soon enough, stories of teens using their entire data allowance in a single day were testament to its success.

That success also attracted suitors. In 2013, Facebook approached the company with a $3bn acquisition offer, the same playbook it had used with Instagram: buy out a potential competitor before it can steal users. Snapchat rebuffed the offer, sparking a cold war between the companies that has continued to this day, with Facebook releasing multiple Snapchat clones and making similar features for its own apps.

When we meet, in one of Snap’s two London offices (a newly refurbished 1,150 sq m site in Soho, which the company outgrew almost as soon as it arrived), Spiegel has just revealed a major redesign of Snapchat, prompted in part by its shaky first nine months as a public company. He has a reputation for slight gawkiness, but he looks comfortable in a sharp, blue suit and an open-necked shirt, and displays an eager curiosity at the Guardian’s photoshoot, born from being part of a generation more used to photographing than being photographed. I half expect him to blurt out: “Oh my God, you can’t post that one!”

Snapchat’s total of 180 million daily users seems like a lot. But following a successful initial public offering that confirmed Spiegel and Murphy as billionaires overnight, Wall Street has started to get nervous about the company. Growth has stalled and investors who were hoping they had found the next Facebook are now wondering what they have bought for their money. That unease, he says, is why he has decided to open up, breaking a reputation for having one of the most controlled images in the industry.

The flaw Wall Street identified was that Snapchat is slightly confusing. The app eschews social media conventions in favour of its own visual language and a host of hidden features that any teen will be able to reel off in a heartbeat, but are almost impossible to find through trial and error.

At the heart of the app is the camera, with every other major feature just one swipe away. Taking and sending pictures is easy enough, but to understand why the app attracts such a diehard fanbase you need to dig deeper. Those “augmented reality” lenses, for instance, are accessed by pressing and holding on the screen and then swiping to select the effect you want; messages from your friends are found by swiping left, but “Stories” from your friends – the day-long rolling updates subsequently adapted by Facebook and incorporated into Messenger, Instagram, WhatsApp and Facebook itself – are found by swiping right. There they sit above Snapchat Discover, the app’s news section, which contains Stories from professional publishers, as well as original content created by Snapchat users and curated by the company.

The app is recognisably the same as the service Spiegel and Murphy released all those years ago and its obstinacies have become trademarks. But a forthcoming redesign will refocus more cleanly around two poles: friends and news.

“For a very long time, we have been trying to clarify, or at least distinguish, the difference between friends and publishers,” Spiegel says. “Like, on the Stories page, do you show friends or publishers first? Because our service was really built on this idea of helping friends communicate, we chose friends – and ultimately what that meant is that all of this awesome publisher content was all the way down at the bottom.”

One obvious solution would have been to take the approach favoured by Facebook, Twitter, and every other social network of note: mix the big professional publishers in with your friends. But that approach has its downsides.

“We had seen on other social media services that the minute you start mixing premium content – publisher content – with your friends is the minute people start feeling uncomfortable posting things that they created themselves.”

This vicious cycle – referred to at Facebook as the fall in “organic sharing” – is the reason for the service’s incessant prods to share memories from your past, to reconnect with old friends and to post themed pictures to celebrate every holiday on the calendar. It’s also why Facebook has started to experiment with following Snapchat by moving news off the main feed altogether. In six small countries, including Cambodia and Bolivia, its test sparked genuine concern for democracy, as readership on the news sites plummeted by more than half and editors warned that their publications would collapse. Facebook scrambled to reassure users in other countries that the change was only a test. Two months on, the “test” continues.

Spiegel seems determined not to present the same impression of world-changing power wielded with an eye only on the revenue. Before we met, he was in Paris to give a speech at the annual gala of the French-American Foundation. There, he cited the French political scientist Alexis de Tocqueville, author of Democracy in America, who both praised and warned against the American passion for individualism.

“Tocqueville had this idea that individualism would undermine democracy. And, as we look at how technology has evolved, it has really empowered us to believe that we are in charge of our own destiny. It certainly has helped perpetuate individualism. And Tocqueville in particular was very focused on this idea that the newspaper was one of the most important tools for helping democracy overcome individualism because it provided a common framework for understanding the world. So, I think the question is: if your friends are the ones who are effectively editing the newspaper that you consume, and if everyone is reading their own newspaper constructed by your friends, what is the bridge to the common understanding and support of freedom and equality that has made democracy so strong?

“We say: if you want to talk with your friends, talk about whatever you want. But if we’re going to give a lot of distribution to someone, we want to make sure that they’re making really high-quality stuff. Or, you know, at a minimum, that someone has looked at what that is.”

Some of this lofty rhetoric can be a bit odd when juxtaposed with the lighthearted lifestyle content that makes up the majority of published stories on Snapchat (sample headlines from the day we meet include “Do girls actually like when you do THIS?”, “Will this fix yellow teeth?” and, “This dog’s best friend is REALLY bizarre”), but Spiegel insists that those who want hard news do find it.

“On my Discover page, I have the Economist, the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. And I have some new shows, one from CNN and one from NBC,” he says. “I would suggest to you that historically there’s always been a spectrum … We’d like to give you lots of choices in terms of the stories that you’d like to watch. Some of it will be very serious and some will be more lighthearted – and I think that speaks to the range of human expression.”

For all Spiegel’s reasoned fear of curation-induced bubbles, Snapchat is introducing some algorithmic filtering to its product, intervening for the first time to change the ordering of Stories and messages. “The Stories page, for a very long time, was ranked exclusively by most recent. So, the people who posted the most were the ones who were always at the top,” he says. Now, friends and publishers will be sorted in a way that is, well, “smart”.

“Research shows that your own past behaviour is a far better predictor of what you’re interested in than anything your friends are doing,” Spiegel wrote in November in a post on the site Axios, announcing the redesign. “This form of machine learning personalisation gives you a set of choices that does not rely on free media or friend’s recommendations and is less susceptible to outside manipulation.”

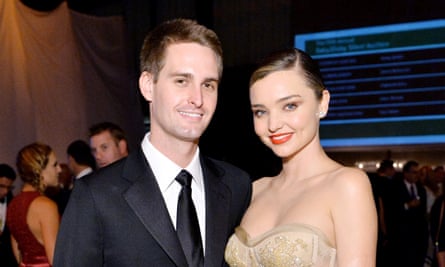

In practice, he says, this means that “I will see my co-workers appear higher up during the work week, during work hours. During the weekend, or around the time I’m heading home from the office and I let Miranda know I’m coming home, she appears higher up in my conversation threads.” (Spiegel is married to the Australian model Miranda Kerr, who he met in 2015 at a Louis Vuitton dinner.)

For news, meanwhile, the curation amounts to shuffling the order of the publications shown, not hiding huge swaths of content from people who may disagree with it. “You can think of the new version of Snapchat Discover like a giant newsstand that has been organised just for you based on what you’re interested in.” With only vetted news organisations able to publish on Snapchat, and without a filter bubble, the hope is that Snapchat can avoid “fake news” and find a way out of it.

It all comes back to that Hirst exhibition and the importance of knowing the difference between the real and the fake, and the times and places where that distinction doesn’t really matter. “I do believe that people understand the difference between imagination, art and information,” says Spiegel. “And I think there’s a lot of work we can do as technologists to make that distinction more clear.” For the teens and twentysomethings using the Snapchat camera to superimpose a hamster over the world or doodle over their own faces, technology can, Spiegel hopes, unlock a creativity people didn’t know they had within them.