Caroline Gleich Fights Back Against Cyber Harassment

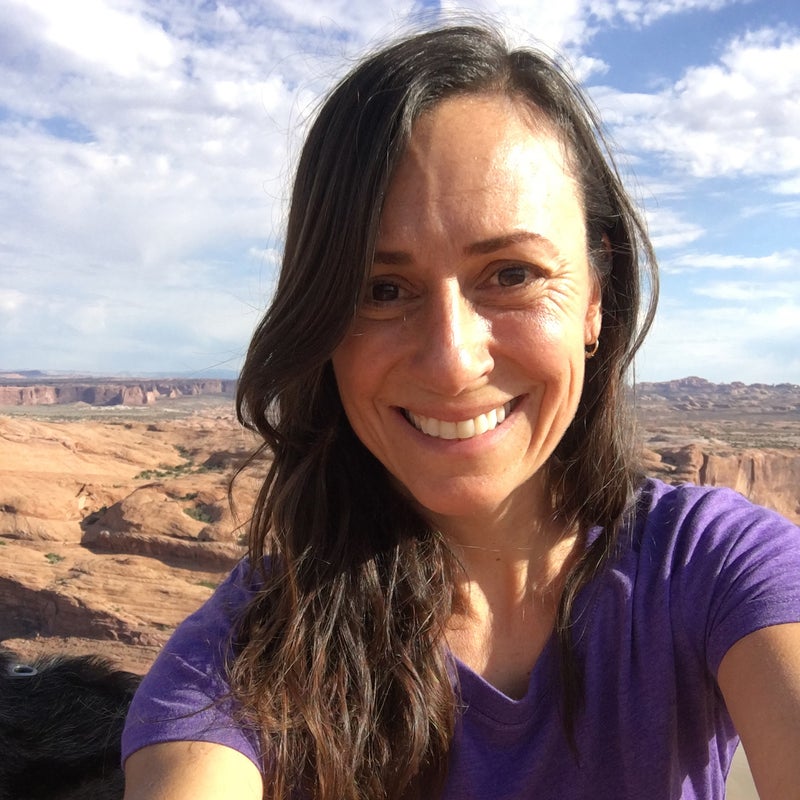

Caroline Gleich’s Instagram feed is full of epic shots of the pro skier conquering the planet’s hardest lines. But in recent years, it was marred by an ugly shadow: anonymous bullies whose abusive comments left a wake of anxiety and doubt. Then Gleich spoke out about her tormenters—and realized she wasn’t the only adventure athlete being harassed online.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

The first time she was harassed online, Caroline Gleich was holed up during a snowstorm in Hokkaido, Japan. It was January 2009, and the skier had been filming all day with Sweetgrass Productions on one of her first major trips as a professional athlete. Gleich and 13 guys were milling about a three-bedroom apartment festooned with drying midlayers and Gore-Tex. The scent of well-used socks and soggy armpits perfumed the air.

After a long day skiing, Gleich sat down and opened her laptop to catch up on e-mail. She clicked on a message from Scott Fisher, an administrator for the popular forums on the website for Teton Gravity Research, another action-sports film company.

How Athletes Respond to Bullying

With few options for dealing with online harassment, individuals are often left to address it on their own.

With few options for dealing with online harassment, individuals are often left to address it on their own.“Someone is using your full name as a screen name, has your blog in their signature area, and is basically making you look like an idiot,” Fisher wrote. “I just wanted to make sure it wasn’t one of your friends fucking around or something before I called them out… Do you know these guys?”

Gleich’s face grew hot as she clicked through the fraudulent posts. “I almost called the police from Japan, because it was such a horrible feeling—anger and rage and embarrassment,” she says. “I mean, one of the posts was about showing off my tits.”

Fisher blocked the user’s IP address and banned them from the site, then he sifted through the posts and deleted each one. Fisher tracked down the user through the site’s internal records and confronted him. The man said he’d known Gleich for eight years and there had been “non-stop joking back and forth.” She remembered meeting him at the University of Utah a few years earlier, but she had never considered him a friend. She decided to drop the issue, and he never posted as her again.

Since then, Gleich has attracted a bevy of big-name sponsors—including Clif Bar, Keen, and Patagonia—and in April became the first woman to complete all 90 ski descents in The Chuting Gallery, the Wasatch Range’s cult-classic guidebook. She has amassed an Instagram following of 129,000 with a feed that is energetic and earnest, filled with photos, ski advice, and pleas for environmental action. But every so often, a seemingly innocuous post sparks a hostile response.

On January 6, 2014, for example, she posted a video about layering strategies for cold-weather climbing.

findingawayaswellasworking: How would you layer for a massive blast of seamen?

On June 19, 2015, she posted about an interview featured in Skiing magazine.

steepassskiing: What’s the difference between Caroline and Suzy Chapstick? Suzy Chapstick can ski!

The jabs felt abrupt and baffling, but she didn’t think much of them—at least at first. She took screenshots (which she later shared with Outside), deleted the comments, and blocked the users. Over the past three years, she estimates that she has collected more than two dozen disparaging comments. Some were disagreements with her political or environmental views, which may not sound like a lot, but they stuck with her. Some called her a dumbass, and one said she was a “fucking joke.” Others questioned her skills and success, as happened a few months after she landed the cover of Powder magazine in December 2013.

illbutterz: How many dix did you suck to get those cover shots? I know it wasn’t based on the merit of your skiing.

Even though most of Gleich’s followers adore her—she typically gets between 20 and 100 positive comments on each Instagram post—the negativity was taxing. “A lot of people say that when you put yourself out there, you just need to deal with this kind of thing,” Gleich says. “But even after deleting the posts and blocking the person, it still got into my psyche.”

Because her detractors were faceless, hiding behind screen names, Gleich worried they could be anyone she met. She became more circumspect about posting her real-time whereabouts. During public talks, she’d scan the sea of faces looking for hostile ones. She started to carry pepper spray when traveling and during solo training runs in the mountains, the demeaning comments lingering in her mind. “They leave you with the creepiest feeling,” she says.

Then, just before Thanksgiving 2016, things escalated. Gleich ski-cut a slope—a common hazard-testing practice among experienced ski mountaineers, guides, and patrollers—in Utah’s Little Cottonwood Canyon and triggered an avalanche. She used the episode to post about snow safety on Instagram. A person she hadn’t seen before, one who had chosen a name that insulted Gleich, piped up.

cgisagumby: Who fuckin triggers an avy intentionally besides patrol? Answer gumbies that don’t belong in the mountains. Shouldn’t be there in the first place. That’s why you are going to end up like Liz!

“Liz” was a reference to Liz Daley, a friend of Gleich’s who had died in an avalanche. The comment hit her like a punch to the gut—especially since Gleich’s half-brother had also died in an avalanche, in 2001. Gleich blocked the user.

On Thanksgiving, after touring Vancouver, British Columbia, and eating dinner with her family, she received a menacing voice mail on her cell phone from a man who didn’t leave his name. He berated her about the avalanche, calling her “cross-eyed” and a “silver-spooned spoiled bitch.” Her boyfriend contacted the police, who assigned a detective to investigate the threatening call and, eventually, the comments.

Gleich started to carry pepper spray when traveling and during solo training runs in the mountains, the demeaning comments lingering in her mind. “They leave you with the creepiest feeling,” she says.

As they did, Gleich spent a lot of time thinking about the insults the users had hurled at her. Many, she believed, exhibited similar patterns as the caller in terms of tone, usage, and themes. “I put all the comments together and was like, I think it’s the same person,” she says. Comments she had received as far back as 2014 accosted her for being privileged. (She grew up in a middle-class family in Minnesota.) Another post had also derided her for being cross-eyed. (She isn’t.)

Whether or not the caller was the one posting comments—and there’s no proof that he was—the call went too far. On December 27, Gleich spoke out in a post on Instagram. “When your bully spends the time to find your phone number and calls to harass you during Thanksgiving dinner, it’s hard to ignore. I know my story is one of many and just the tip of the iceberg. It happens to so many people. I’m tired of being silenced by it and silent about it. I’m taking a stand against cyberbullying.”

Everyone knows how vitriolic online chatter can be. Internet users often react more intensely—and disclose more private information—than they would in person, a phenomenon psychologists refer to as the online disinhibition effect. What’s more, it’s difficult to enforce social norms in the faceless world of the Internet.

“Think of what would happen if someone started hollering weird sexual things at someone at a cocktail party. It wouldn’t be tolerated,” says Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center, a California nonprofit.

Cyberharassment can take a variety of forms, including name-calling, impersonation, dogpiling (when a group of people, known as a cybermob, harass a user), and doxing (when someone publishes an individual’s contact info publicly). According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, 41 percent of American adults have experienced some form of cyberharassment, up from 35 percent three years ago. Eighteen percent reported that they’d been the victims of more serious online harassment, including physical threats and stalking.

As visible figures, athletes have always faced hecklers. But it has never been easier for fans and viewers to communicate with them directly. Almost all the individuals I spoke with genuinely enjoy social media—it allows them to share their accomplishments, build followings, and attract sponsors. Besides, there’s a high opportunity cost for opting out. Many outdoor brands now include social-media clauses in their contracts, requiring sponsored athletes to post at a certain frequency, share brand-related content, or at least maintain active feeds.

Some athletes also agree to post sponsored content from brands, which can bring in more than $3,000 per post and form a significant amount of their income. Few statistics exist on adventure athletes and social-media use, but among the more than two dozen professional outdoor athletes I interviewed (of whom two-thirds were women), more than 75 percent reported receiving nasty posts from followers.

“Unfortunately, it’s skewed toward women,” says Jimmy Sanderson, author of It’s a Whole New Ballgame: How Social Media Is Changing Sport. “For women the criticism is often more appearance, image, and gender based, while with men it’s more performance based.”

“Not in a million years would they say this stuff in person, because they know they’d get punched right in the face,” says BASE jumper and wingsuit pilot Jeb Corliss, who estimates that 95 percent of his interactions online are great and about 5 percent are terrible. “When they’re behind a keyboard and a screen name, they feel they can vent their frustrations and anger and rage.”

With outdoor athletes, many negative comments appear to be motivated by envy, as users follow what looks like an incredible lifestyle recorded through splashy photos. “This kind of marketing naturally breeds a bit of jealousy and resentment for some people,” says climber Emily Harrington, “especially when they can hide behind the mask of the Internet.”

Some harassment goes beyond the scope of ordinary human emotions, however. Impersonators have targeted athletes like Gleich and former pro mountain biker Nicola Cranmer, publishing hurtful posts on fraudulent accounts. Cyberstalkers are more rare, but I interviewed a female rock climber and a female skier who said they’d been stalked. Both declined to speak on the record because they didn’t want to provoke their stalkers or relive the emotional trauma.

Rarer are the cyberbullies who cross the virtual line into real life. In the early days of Usenet groups, ski mountaineer Andrew McLean befriended a skier online who then turned on him. “He started driving around and sending me e-mails like, ‘Oh, I noticed you weren’t in last night and your lights went out at ten o’clock,’ ” says McLean, who ignored the person and left the user group.

Corliss estimates that he’s had five to ten cyberstalkers over the years. Sometimes they start out wanting some kind of relationship, he says, then turn obsessive and threatening. “I am usually able to neutralize people because I’m just so damn terrifying,” says Corliss. “I jump off buildings for fun—you really think you’re going to scare me? But a truly crazy person isn’t scared. Your only hope is that their craziness will shift to someone else.” For about a third of those who are harassed online, the abuse is perpetrated by multiple people—sometimes an organized mass but often a pile-on of users who get swept up in group sentiment and disconnect from the target’s humanity. Kristin Armstrong, a 44-year-old cyclist who won two Olympic gold medals in the time trial, faced this when she decided to come out of retirement in 2015. That year, USA Cycling chose two women to represent the country in the event, based largely on international results and past racing history.

Armstrong and Evelyn Stevens made the team to go to the Rio Games; the decision devastated Carmen Small, the 2016 national time-trial champion, and she contested the decision. Cyclists, fans, and industry insiders took to the Internet in droves, calling the selection process biased—since it is partly based on coaches’ discretion—and Armstrong started to see personal attacks online, calling her old and boring. Some said she should step aside. Over the course of weeks, dozens of critical messages, comments, and news stories cropped up. “Two weeks before the Olympic Games, I didn’t believe I could compete,” Armstrong says. “I was so wound up and stressed, I couldn’t sleep at night. All I could do was think about what these people had to say.”

At the suggestion of a coach, Armstrong deleted all the social-media apps from her phone. In Rio, she won her third gold medal, becoming the most decorated female cyclist in U.S. history. The critics were silenced, but even after the medal hoopla she felt lasting emotional effects. “To this day, it makes me anxious and really mad,” Armstrong says.

For Joe Kinder, a rock climber sponsored by La Sportiva and Black Diamond, the attacks of a cybermob were so eviscerating that he contemplated suicide. In September 2013, while putting up new routes in the Lake Tahoe area, Kinder cut down two trees—one living and one dead—at the base of the crag, so that no one would fall into them, a common practice when developing sport-climbing routes.

What Kinder didn’t realize before a fellow climber posted a photo on Instagram was that it is illegal to cut down juniper trees in the area. Over the following days and weeks, he received hostile phone calls from strangers, insulting comments on his blog and on Instagram, and even death threats. He publicly apologized for his mistake, but the posts kept coming. “I was fucking scared. I was really upset, really sad, really depressed,” says Kinder. “Being the target of a hate mob was the worst experience I’ve ever had in my life.”

Online harassment can have profound effects on victims, but it’s surprisingly hard to combat. The major social platforms—Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Snapchat—allow users to block people and report complaints through online submission forms, but it’s often unclear what happens after that. In some instances, the companies will shut down a harasser’s account, but complaints can go unaddressed for weeks or even months. (Facebook and Instagram said that they typically respond within 24 hours.)

Some platforms are working on tools to prevent abuse. In June, for example, Instagram released a filter designed to weed out ugly comments on personal feeds.

Part of the challenge of confronting the issue: When does garden-variety meanness become harassment? The line is subjective. The Pew Research Center defines it as anything from name-calling to stalking. Danielle Citron, a University of Maryland law professor and the author of Hate Crimes in Cyberspace, defines it in her book as sustained online speech intended to inflict emotional harm. Each state has its own legal definition.

In cases of persistent harassment, victims can pursue civil and criminal suits, but it’s typically an onerous path. A few police departments, including those in Los Angeles and Boston, have dedicated cybercrime units, but cyberbullying cases often fall to local detectives. To unmask a user’s identity, a police officer or lawyer must first subpoena the social network to determine user IP addresses, then subpoena the user’s Internet provider to obtain the identities associated with the addresses. The process can take months, and it isn’t always successful.

“Two weeks before the Olympic Games, I didn’t believe I could compete,” Armstrong says. “I was so wound up and stressed, I couldn’t sleep at night. All I could do was think about what these people had to say.”

That leaves athletes themselves and the brands that sponsor them to deal with the issue. Of the half-dozen brand spokespeople I interviewed, all were aware of the problem on some level but either said that their athletes weren’t affected or that their companies steer clear of getting involved.

“It would have to be pretty extreme for a brand to step in for an athlete,” says Maro LaBlance, a public relations manager who represents outdoor companies Eider, Picture, and Saola. One spokesperson who asked to remain anonymous said that companies could probably do more to help athletes alert social-media networks about abuse, since they often have direct access to the platforms’ advertising representatives.

Some brands are working to educate their athletes on how to manage trolls, hecklers, and abusers. The North Face has shared social-media guidelines—including how to deal with trolls—at its athlete summits since 2013. Patagonia discussed the topic for the first time at an ambassador meeting in September. Many high school and college athletic departments now offer social-media training. The International Olympic Committee plans to release guidelines in November to help sports organizations safeguard athletes from harassment and abuse.

Many athletes, however, told me that even though they receive nasty comments, they don’t define it as harassment. Instead they accept mean comments and name-calling as inevitable fallout from being a public figure.

“I’m a millennial and got called names 100 times a day on ski forums as a 13-year-old,” says skier Brody Leven, 29. “I’m pretty much used to it. I don’t want it to be culturally OK, but I think we have to be able to accept it.”

When Gleich came forward about cyberbullying last December, the response was overwhelmingly positive—she received 498 supportive comments. But the incidents didn’t stop. On January 16, she wrote a post about Martin Luther King, Jr.

climbskipuff: You’re unintelligent misinformed jerk and when you end up like Liz we are going to have a Huge party! Just go away @carolinegleich!

Around the same time, she blocked a user named ill_butterz who started mocking her on his own feed, even making fun of her for speaking out about her bully. (The user name was a variation of another handle, illbutterz, that she’d blocked in 2014.)

In March and April, she filed several complaints through Instagram’s site about ill_butterz, and the service removed the posts. She also posted an Instagram Story—a series of videos and photos that disappear after 24 hours—that addressed her experience and asked followers if they knew the user. About 50 people responded with messages of support, and three privately messaged her that they knew the identity of ill_butterz. She played the Thanksgiving message for one of them, and he said the voice sounded like the person he suspected. Outside obtained the phone number of that person—which, it turned out, also matched the one that had called Gleich—and reached out to him in September. He denied ever calling Gleich and said he wasn’t sure how a message from his number ended up on her voice mail. He also said he has no connection to the user name ill_butterz.

Meanwhile, police were able to track the IP addresses of nine of the harassing comments Gleich received and told her that none of them matched, suggesting that the comments came from more than one person—or, at the very least, more than one device or location. In all likelihood her case, like most cyberbullying investigations, will never be resolved to her satisfaction. “Ultimately, I just want him to stop, and he has,” Gleich says. “If it starts up again, I’ll pursue more aggressive action.”

Whether one harasser or many, athletes are largely left to deal with the harassment on their own. Some of them have had success with a relatively simple approach: addressing snarky commenters head-on. The climber and BASE jumper Steph Davis, for example, has occasionally taken a kill-them-with-kindness approach. It’s not uncommon, she says, for users to be a little embarrassed about reacting so strongly. Some even apologize. After her win in Rio, Kristin Armstrong received several apology letters from people who had tweeted or posted odious missives. Many of the haters Joe Kinder contacted softened their stance when they heard from him. (Gleich tried this a few times and was met with sarcasm.)

Other commenters unapologetically stand by their rhetoric. One of them is Andrew Heidt, from Erie, Pennsylvania, who commented on an April 12, 2017 story about Gleich’s harassment on the mountain-sports website Unofficial Networks. The story’s comment section was rife with barbs. “Reach out to local authorities hahaha. Quit crying and just fuckin deal with it,” Heidt wrote. “Get the troll back. You ride the mountains at will, take the high road.” When I interviewed Heidt through Facebook Messenger (he didn’t want to e-mail or speak by phone), he said that harsh speech online was not OK, but he felt that his comment didn’t count as harsh speech. “If she was my friend,” he typed, “I’d tell her the same thing to her face.”

According to the Pew Research Center survey, nearly 80 percent of us believe that social-media companies have a responsibility to police their feeds. But that doesn’t absolve the online community. While groups of Internet users can cause harm, they can also come to the rescue. Right now, experts argue that the best way to combat negative posts is what’s known as bystander intervention: call out a bully’s behavior, send a supportive message to the target, or report the behavior. Before Unofficial Networks took down its story at Gleich’s request, several commenters—mostly women—stood up for Gleich.

Mollie Niess: Simply block the number? Sigh. She shouldn’t have to. How about this jackass stops harassing her?

“It can be really simple to say, ‘That kind of talk, we don’t tolerate it,’ ” says Gleich. “It’s like something you’d say to a three-year-old who punches another kid on the playground.”

Since calling out ill_butterz on Instagram last April, Gleich hasn’t received any unpleasant phone calls or comments. She continues to post colorful snapshots of herself skiing on a bluebird day or smiling at the other end of her outstretched arm, mountains receding in the distance. If a recent post about her love of glaciers is any indication, Gleich’s audience is a throng of doting fans.

springmcclurg: Beautiful, Caroline!!! So happy to have people like you sharing the love for wild places and inspiring people to protect and share these incredible places!

javisiesta: Beautiful pic! Beautiful message!

“The way my community has mobilized and is ready to help if something comes up, it’s amazing,” says Gleich. “I realized I have an army behind me.”

Kate Siber (@katesiber) is an Outside correspondent. She wrote about upscale meditation studios in August.