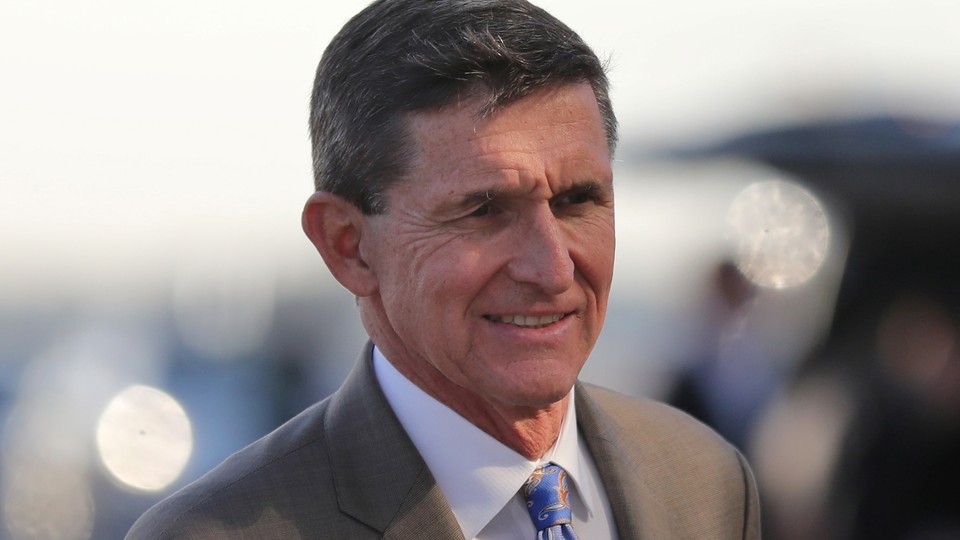

Why the White House Dreads a Flynn Indictment

Unlike the Paul Manafort case, charges against the former national-security adviser would touch the White House itself and could ensnare the president.

In the indictments sweepstakes ahead of last week’s first moves by special counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia probe, Paul Manafort was the odds-on favorite, but Michael Flynn, the former national-security adviser, was a good bet too.

Monday, and the rest of the week, came and went, bringing indictments for Manafort and his deputy Rick Gates and a guilty plea from George Papadopoulos, but nothing on Flynn. But NBC News reported over the weekend that federal investigators have enough evidence to charge Flynn, and that’s a prospect that should be particularly worrisome to the White House.

It’s worth noting that Flynn might already have been indicted. Papadopoulos’s guilty plea, for example, came on October 5 but wasn’t revealed until October 30; he was arrested months earlier. There’s speculation that Mueller’s grand jury may have already handed down new indictments that haven’t been unsealed yet.

Whether a Flynn indictment is sealed or still forthcoming, any charges would make the administration’s situation, already complex, even more headache-inducing. From any rational point of view, the Manafort indictment was bad news for President Trump: No one wants a former campaign chairman to be accused of moving around $75 million, and charged with money laundering and lying to the federal government. But the White House quickly adopted a positive spin, noting that the charges concerned behavior before Manafort joined the Trump campaign.

As I wrote last week, that reflects poorly on Trump as a judge of character and as an employer, but it also allowed the president to distance himself from the investigation and point out that none of the charges against Manafort indicated collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia. (The Papadopoulos plea, though somewhat enigmatic, struck much closer to that matter.) As Trump made that point publicly, The Washington Post and Axios both reported that staffers inside the White House were relieved that Manafort had been charged, rather than Flynn.

The charges that Flynn seems most likely to face are similar to some that were brought against Manafort. Like Manafort, Flynn did not register under the Foreign Agent Registration Act at the time he did work for foreign governments, though like Manafort, he retroactively registered. Like Manafort, who is charged with making false statements, Flynn may have lied to the FBI. Flynn was pushed out of his job as national-security adviser on February 14, making him the shortest-tenured holder of that job in history, after the Post revealed that he had lied to Vice President Mike Pence and others about conversations he had with then-Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak. But the paper later reported that Flynn had also lied to the FBI about those conversations.

There are also other counts on which Flynn might be in trouble: His conversations with Kislyak could violate a law that prevents private citizens from conducting foreign policy, though it has never successfully been used to prosecute an American, and many analysts doubt it will be here. There is scrutiny of Flynn’s work for Turkey, for which he retroactively filed under FARA, including an alleged scheme to kick Fethullah Gulen, a cleric and enemy of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan out of the country. Members of Congress have focused on trips he made overseas, including one to celebrate the anniversary of the Kremlin propaganda network RT. As a former top general, Flynn was required to seek permission to be paid for those trips, and he also stands accused of not disclosing them when seeking renewed security clearance. Flynn was also involved in a bizarre Middle Eastern civil-nuclear scheme.

Whatever the superficial similarities between the Manafort and Flynn situations, though, the key difference is that a Flynn indictment would put the Mueller probe in the White House. Manafort was pushed out of the campaign in August and never worked in the Trump administration (though he is said to have remained in contact with Trump for months). Flynn, however, worked in the White House for almost a month. That means he could have discussed many of the potential areas for charges—from conversations with Kislyak to Gulen to who knows what—with any number of White House staffers on any level. Mueller could call them in for questioning. Even if none of those staffers did anything illegal, and at this point there’s no indication they did, the threat of testimony will create new stress and distraction in a White House already riven with both. They’ll also all need lawyers, and good expensive ones; the Papadopoulos plea-deal is a vivid illustration of the dangers of talking to federal agents. (Trump has offered to contribute $430,000 to legal fees, but the more staffers involved, the faster that will be used up.)

Moreover, a Flynn investigation would move things much closer to Trump himself. The president distanced himself from Manafort—former Press Secretary Sean Spicer claimed he played a “very limited role” in the campaign—but not from Flynn. Trump allowed Flynn to stay in the administration even after it became clear he had lied to Pence, and also after a conversation between then-Acting Attorney General Sally Yates and White House Counsel Don McGahn. Yates would not divulge the contents of that late-January conversation when she testified to Congress in May, but if Flynn did lie to the FBI, it appears likely that Yates told McGahn then.

Then, after Flynn’s departure, Trump asked then-FBI Director James Comey if he could let Flynn go, saying he was a good guy, according to sworn testimony Comey offered to Congress. “General Flynn at that point in time was in legal jeopardy,” Comey said in June. “There was an open FBI criminal investigation of his statements in connection with the Russian contacts, and the contacts themselves, and so that was my assessment at the time.” Then, several months later, Trump fired Comey, a decision he attributed to Comey’s investigation into Russian interference in the election.

That creates two separate occasions on which Trump could potentially have obstructed justice—first by meddling in the FBI’s probe into Flynn, then by firing Comey altogether. As the law professor Ryan Goodman writes at Just Security, it would be possible to make an obstruction-of-justice case against Trump in the absence of charges against Flynn, but it’s much more straightforward to make such a case if there’s actual evidence of a case that Trump was attempting to obstruct. Actual criminal charges against Flynn would provide that.

No wonder the Trump team was pleased that Manafort, rather than Flynn, took the first hit—but that relief could be short-lived. Even if one takes Trump’s staunch denials of collusion with Russia entirely at face value, that doesn’t mean Robert Mueller can’t go after him on obstruction of justice or something else entirely. A Flynn indictment is the shortest path to that outcome.