Machine learning has returned with a vengeance. I still remember the dark days of the late '80s and '90s, when it was pretty clear that the current generation of machine-learning algorithms didn't seem to actually learn much of anything. Then big data arrived, computers became chess geniuses, conquered Go (twice), and started recommending sentences to judges. In most of these cases, the computer had sucked up vast reams of data and created models based on the correlations in the data.

But this won't work when there aren't vast amounts of data available. It seems that quantum machine learning might provide an advantage here, as a recent paper on searching for Higgs bosons in particle physics data seems to hint.

Learning from big data

In the case of chess, and the first edition of the Go-conquering algorithm, the computer wasn't just presented with the rules of the game. Instead, it was given the rules and all the data that the researchers could find. I'll annoy every expert in the field by saying that the computer essentially correlated board arrangements and moves with future success. Of course, it isn't nearly that simple, but the key was in having a lot of examples to build a model and a decision tree that would let the computer decide on a move.In the most-recent edition of the Go algorithm, this was still true. In that case, though, the computer had to build its own vast database, which it did by playing itself. I'm not saying this to disrespect machine learning but to point out that computers use their ability to gather and search for correlations in truly vast amounts of data to become experts—the machine played 5 million games against itself before it was unleashed on an unsuspecting digital opponent. A human player would have to complete a game every 18 seconds for 70 years to gather a similar data set.

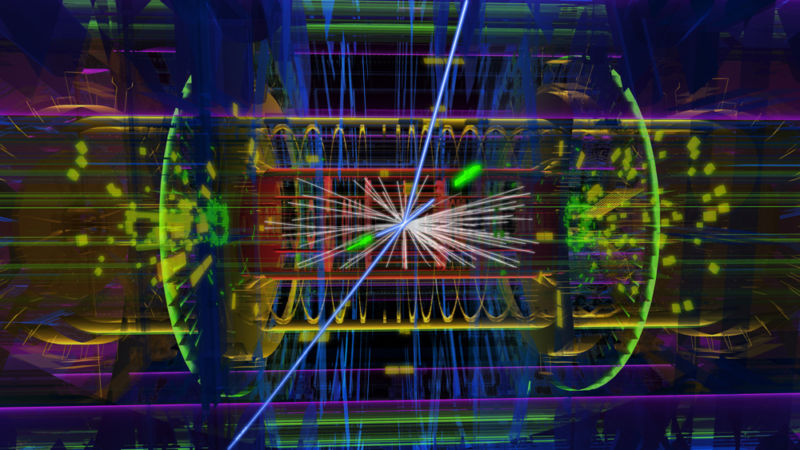

Sometimes, however, you have a situation that would be perfect for this sort of big-data machine learning, except that the data is actually pretty small. This is the case for evaluating Higgs Boson observations. The LHC generates data at inconceivable rates, even after lots of pre-processing to remove most of the uninteresting stuff. But even in the filtered data set, collisions that generate a Higgs boson are pretty rare. And those particle showers that look like they might have a Higgs? Well, there is a large background that obscures the signal.

In other words, this is a situation where a few events must be found inside a very large data set, and the signal looks remarkably similar to the noise. That makes it quite difficult to apply machine learning, let alone train the algorithm in the first place.

Loaded for Higgs

This is exactly the challenge that a group of researchers have taken up. They used a model for Higgs production and a second model that generates the expected background to generate thousands of fake collisions. This is data that would be nearly at the end of the normal process by which we'd search for the Higgs. The collision has already been selected as seeming to be an interesting one. The mass region relevant to the Higgs looks like it might have something worth closer examination. Just that tiny portion of the data must be refined from a "may contain traces of Higgs" state to a definitive "contains Higgs" or "Higgs free."

To do that, the researchers went through the physics of a single type of collision that produces a Higgs boson: two gluons collide, and via a love triangle of two virtual top quarks and a virtual anti-top quark, they produce a Higgs boson. The Higgs boson meanders off and falls apart, releasing two high-energy photons. The detector only registers the following: the energy of the photons and their angle with respect to the beam. From that, you can figure out how much momentum, in the direction perpendicular to the beam, the photons have (called transverse momentum).

The momentum by itself is not so useful; you can't look at the transverse momentum of one of the photons and say "Aha, I've found a Higgs boson." No, the presence of the Higgs is revealed by correlated changes in combinations of these basic parameters. Unfortunately, no one can really say exactly what combinations are most sensitive. So instead of trying to guess, the researchers used all of them. They combined the parameters in every conceivable way—for instance, the difference in the two transverse momenta—to create variables that all have a different sensitivity to the Higgs. In the end, they came up with 36 different combinations of the main parameters to test.

Quantum bullets

To test if quantum machine learning might be good at sorting through these combinations, the researchers programmed a quantum computer to try to optimize the 36 parameters to fit the given data and subsequently classify the data as either containing a Higgs or not. There is some detail that I'm going to miss here, but the entire problem is essentially set up so that it is encoded in the strength of links between a grid of quantum magnets (actually superconducting quantum interference devices). The values of the parameters reach their optimum value when the sum of all the energies of the magnets is at a minimum, and the value of the minimum energy is used to decide Higgs/no Higgs. Ars has a more complete description of the computer involved, which was made by D-Wave.To increase the sensitivity of the algorithm further, the team also used the size of the gap between the minimum energy and first excited state (e.g., the size of the smallest possible change in energy from the ground state) to help discriminate between Higgs/no Higgs. The idea being that when the algorithm found a deep minimum, it was more likely to have found a Higgs.

Along with that, the researchers could effectively switch individual parameters on and off so that they could see which were sensitive to the presence of the Higgs and which were not. In the end, they identified a set of three that were most sensitive and several that were completely insensitive, including the transverse mass of one of the emitted photons (meaning the presence of the Higgs was not sensitive to one of the directly measured parameters).

Using this data, and after training, the quantum algorithm could distinguish between data that contained a Higgs boson and data that did not.

So far so good. But there are a bunch of non-quantum machine learning algorithms that should be able to do the same. The researchers chose several of them and set them loose on the data. They obtained similar results: almost all the methods provide about the same degree of success in separating Higgs/no-Higgs data.

Searching for needles having never seen a needle

The important difference between the classical and quantum algorithms was the size of the training data set. For algorithms trained on around 200 collisions, the quantum algorithm significantly outperforms the classical algorithms. I think this is probably the more important finding. For very sparse data sets, we need to have machine learning algorithms that can learn from just a few examples.

On the other hand, the quantum algorithm is significantly worse than the classical algorithms after training on large data sets. This, however, is probably a product of the performance of the underlying hardware rather than the actual algorithm.

There is one other advantage that the researchers have ensured applies to their algorithm. In many machine-learning systems, the machine creates its own set of variables and an internal model. This model is not a reflection of reality, and the variables make no physical sense—all that matters is that it works. But in this case, the researchers chose the variables, which have physical meaning. That means the researchers can gain insight by studying how these variables change between different data sets.

I must admit to being faced with the unenviable task of changing my mind. In the past, I have been highly skeptical of machine learning and artificial intelligence in general. I was astonished at a recent conference when a speaker claimed that current AI was about the equivalent of a cat, a claim I find hard to credit. That overly skeptical attitude has been compounded by learning about some of the inherent bias and atrocious missteps that machine learning systems are making.

However, I must admit that machine learning is getting better, and developers are more aware of the bias-in-bias-out problem. It is inevitable that AI systems will do more and more tasks, even if they are limited to the role of assistants. At this point, there is not a single profession that I would say is safe from artificial intelligence, except those jobs that are too boring for an AI to be interested in learning.

Nature, 2017, DOI: 10.1038/nature24047

reader comments

45