Among the 44 million Americans who have amassed our nation’s whopping $1.4tn in student loan debt, a call from Navient can produce shivers of dread.

Navient is the primary point of contact, or the “servicer”, for more student loans in the United States than any other company, handling 12 million borrowers and $300bn in debt. The company flourished as student loan debt exploded under the Obama administration, and its stock rose sharply after the election of Donald Trump.

But Navient also has more complaints per borrower than any other servicer, according to a Fusion analysis of data. And these mounting complaints repeatedly allege that the company has failed to live up to the terms of its federal contracts, and that it illegally harasses consumers. Navient says most of the ire stems from structural issues surrounding college finance – like the terms of the loans, which the federal government and private banks are responsible for – not about Navient customer service.

Yet during a year-long investigation into who profits off of what has become the largest source of American consumer debt, Fusion TV untangled how Navient has positioned itself to dominate the lucrative student loan industry in the midst of this crisis, flexing its muscles in Washington and increasingly across the states. The story of Navient’s emerging power is also the story of how an industry built around the idea that education can break down inequities is reinforcing them.

The tension at the center of the current controversy around student loans is simple: should borrowers be treated like any other consumers, or do they merit special service because education is considered a public good?

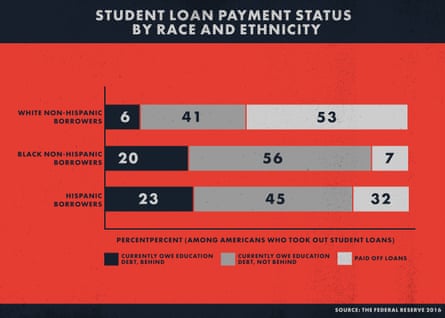

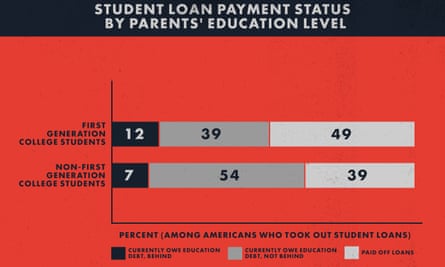

Often, the most vulnerable borrowers are not those with the largest debt, but low-income students, first-generation students, and students of color – especially those who may attend less prestigious schools and are less likely to quickly earn enough to repay their loans, if they graduate at all.

“There are populations who are borrowing to go to college or ending up without a degree, and ending up with meaningless degrees, and are ... worse off than if they had never gone to college to begin with,” said Amy Laitinen, of the nonpartisan thinktank New America.

Last year, Navient received 23 complaints per 100,000 borrowers, more than twice that of the nearest competitor, according to Fusion’s analysis. And from January 2014 to December 2016, Navient was named as a defendant in 530 federal lawsuits. The vast majority were aimed at the company’s student loans servicing operations. (Nelnet and Great Lakes, the two other biggest companies in the student loans market, were sued 32 and 14 times over the same period, respectively.)

Many of the complaints and lawsuits aimed at the company relate to its standard practice of auto-dialing borrowers to solicit payments.

Shelby Hubbard says she has long been on the receiving end of these calls as she has struggled to pay down her debt. Hubbard racked up over $60,000 in public and private student loans by the time she graduated from Eastern Kentucky University with a basic healthcare-related degree.

“It consumes my every day,” Hubbard said of the constant calls. “Every day, every hour, starting at 8 o’clock in the morning.” Unlike mortgages, and most other debt, student loans can’t be wiped away with bankruptcy.

These days, Hubbard, 26, works in Ohio as a logistics coordinator for traveling nurses. She’s made some loan payments, but her take-home pay is about $850 every two weeks. With her monthly student loan bill at about $700, roughly half her income would go to paying the loans back, forcing her to lean more heavily on her fiance.

“He pays for all of our utilities, all of our bills. Because at the end of the day, I don’t have anything else to give him,” she said. The shadow of her debt hangs over every discussion about their wedding, mortgage payments, and becoming parents.

The power and reach of the student loan industry stacks the odds against borrowers. Navient doesn’t just service federal loans, it has a hand in nearly every aspect of the student loan system. It has bought up private student loans, both servicing them and earning interest off of them. And it has purchased billions of dollars worth of the older taxpayer-backed loans, again earning interest, as well as servicing that debt. The company also owns controversial subsidiary companies such as Pioneer Credit Recovery that stand to profit from collecting the debt of loans that go into default.

And just as banks have done with mortgages, Navient packages many of the private and pre-2010 federal loans and sells them on Wall Street as asset-backed securities. Meanwhile, it’s in the running to oversee the Department of Education’s entire student debt web portal, which would open even more avenues for the company to profit from – and expand its influence over – Americans’ access to higher education.

The federal government is the biggest lender of American student loans, meaning that taxpayers are currently on the hook for more than $1tn. For years, much of this money was managed by private banks and loan companies like Sallie Mae. Then in 2010, Congress cut out the middlemen and their lending fees, and Sallie Mae spun off its servicing arm into the publicly traded company Navient.

Led by former Sallie Mae executives, Navient describes itself as “a leading provider of asset management and business processing solutions for education, healthcare, and government clients.” But it is best known for being among a handful of companies that have won coveted federal contracts to make sure students repay their loans. And critics say that in pursuit of getting that money back, the Department of Education has allowed these companies to all but run free at the expense of borrowers.

“The problem is that these servicers are too big to fail,” said Persis Yu, director of the National Consumer Law Center’s Student Loan Borrower Assistance Project. “We have no place to put the millions of borrowers whom they are servicing, even if they are not doing the servicing job that we want them to do.”

In its last years, the Obama administration tried to rein in the student loan industry and promoted more options for reduced repayment plans for federal loans. Since then, Donald Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos, has reversed or put on hold changes the former education secretary John B King’s office proposed and appears bent on further loosening the reins on the student loan industry, leaving individual students little recourse amid bad service.

In late August, DeVos’s office announced that it would stop sharing information about student loan servicer oversight with the federal consumer watchdog agency known as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, or CFPB.

Earlier this year, as complaints grew, the CFPB sued Navient for allegedly misleading borrowers about the repayment options it is legally obligated to provide.

A central allegation is that Navient, rather than offering income-based repayment plans, pushed some people into a temporary payment freeze called forbearance. Getting placed into forbearance is a good Band-Aid but can be a terrible longer-term plan. When an account gets placed in forbearance, its interest keeps accumulating, and that interest can be added to the principal, meaning the loans only grow.

Lynn Sabulski, who worked in Navient’s Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, call center for five months starting in 2012, said she experienced first-hand the pressure to drive borrowers into forbearance.

“Performing well meant keeping calls to seven minutes or under,” said Sabulski. “If you only have seven minutes, the easiest option to put a borrower in, first and foremost, is a forbearance.” Sabulski said if she didn’t keep the call times short, she could be written up or lose her job.

Navient denies the allegations, and a spokeswoman told Fusion via email seven and a half minutes was the average call time, not a target. The company maintains “caller satisfaction and customer experience” are a significant part of call center representatives’ ratings.

But in a 24 March motion it filed in federal court for the CFPB’s lawsuit, the company also said: “There is no expectation that the servicer will act in the interest of the consumer.” Rather, it argued, Navient’s job was to look out for the interest of the federal government and taxpayers.

Navient does get more per account when the servicer is up to date on payments, but getting borrowers into a repayment plan also has a cost because of the time required to go over the complex options.

The same day the CFPB filed its lawsuit, Illinois and Washington filed suits in state courts. The offices of attorneys general in nine other states confirmed to Fusion that they are investigating the company.

At a recent hearing in the Washington state case, the company defended its service: “The State’s claim is not, you didn’t help at all, which is what you said you would do. It’s that, you could’ve helped them more.” Navient insists it has forcefully advocated in Washington to streamline the federal loan system and make the repayment process easier to navigate for borrowers.

And it’s true, Navient, and the broader industry, have stepped up efforts in recent years to influence decision makers. Since 2014, Navient executives have given nearly $75,000 to the company’s political action committee, which has pumped money mostly into Republican campaigns, but also some Democratic ones. Over the same timespan, the company has spent more than $10.1m lobbying Congress, with $4.2m of that spending coming since 2016. About $400,000 of it targeted the CFPB, which many Republican lawmakers want to do away with.

Among the 22 former federal officials who lobby for Navient is the former US representative Denny Rehberg, a Republican, who once criticized federal aid for students as the welfare of the 21st century. His fellow lobbyist and former GOP representative Vin Weber sits on a board that has aired attack ads against the CFPB, as well as on the board of the for-profit college ITT Tech, which shuttered its campuses in 2016 after Barack Obama’s Department of Education accused it of predatory recruitment and lending.

In response to what they see as a lack of federal oversight, California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and the District of Columbia recently required student loan servicers to get licenses in their states. Not surprisingly, Fusion found a sharp increase in Navient’s spending in states considering such regulations, with the majority of the $300,000 in Navient state lobbying allocated since 2016.

In Maine and Illinois, the legislatures were flooded with Navient and other industry lobbyists earlier this year, after lawmakers proposed their own versions of the license bills. The Maine proposal failed after Navient argued the issue should be left to the federal government. The Illinois bill passed the legislature, but the Republican governor, Bruce Rauner, vetoed it in August following lobbying from an industry trade group. Rauner said the bill encroached on the federal government’s authority.

Researchers argue more data would help them understand how to improve the student loan process and prevent more people from being overwhelmed by debt. In 2008, Congress made it illegal for the Department of Education to make the data public, arguing that it was a risk for student privacy. Private colleges and universities lobbied to restrict the data. So, too, did Navient’s predecessor, Sallie Mae, and other student loan servicing companies.

Today, companies like Navient have compiled mountains of data about graduations, debt and financial outcomes – which they consider proprietary information. The lack of school-specific data about student outcomes can be life-altering, leading students to pick schools they never would have picked. Nathan Hornes, a 27-year-old Missouri native, racked up $70,000 in student loans going to Everest College, an unaccredited school, before he graduated.

“Navient hasn’t done a thing to help me,” Hornes told Fusion. “They just want their money. And they want it now.”

Hornes’ loans were recently forgiven following state investigations into Everest’s parent company Corinthian. But many other borrowers still await relief.

Better educating teens about financial literacy before they apply to college will help reduce their dependence on student loans, but that doesn’t change how the deck is stacked for those who need them. A few states have made community colleges free, reducing the need for student loan servicers.

But until the Department of Education holds industry leaders like Navient more accountable, individual states can fix only so much, insists Senator Elizabeth Warren, one of the industry’s most outspoken critics on Capitol Hill.

“Navient’s view is, hey, I’m just going to take this money from the Department of Education and maximize Navient’s profits, rather than serving the students,” Warren said. “I hold Navient responsible for that. But I also hold the Department of Education responsible for that. They act as our agent, the agent of the US taxpayers, the agent of the people of the United States. And they should demand that Navient does better.”

Laura Juncadella, a production assistant for The Naked Truth also contributed to this article

The Naked Truth: Debt Trap airs on Fusion TV 10 September at 9pm ET. Find out where to watch here

- This article was updated on 6 September 2017 to correct the spelling of Denny Rehberg’s surname. We originally had it as Rehlberg.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion