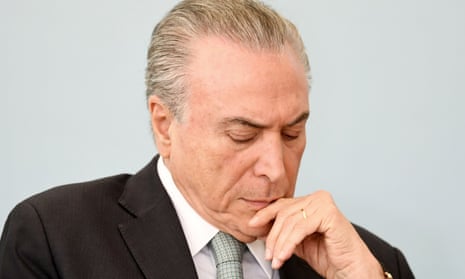

If Brazil’s recent decline could be plotted in the falling popularity of its presidents, Michel Temer represents the bottom of the curve.

In 2010, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva ended his second term with an 80% approval rating. In March 2016 – four months before she was impeached – his protege and successor Dilma Rousseff’s administration had a 10% rating.

Last month, the government of Temer, Rousseff’s former vice-president, plunged to 3% in one poll. Among under 24-year-olds, Temer’s approval hit zero.

Temer has been charged with corruption, racketeering and obstruction of justice. Yet there have been none of the huge, anti-corruption street protests that helped drive Rousseff’s impeachment on charges of breaking budget rules.

And unlike Rousseff, Temer has retained the support of financial markets who like the austerity measures he has introduced, such as privatising government services, a 20-year cap on expenditure and a planned pensions overhaul.

There are signs of economic recovery. But spending has been so pared to the bone that some basic functions of the state are now at risk.

Critics say Temer’s austerity drive hurts the poor more than the rich. According to a survey by Oxfam Brasil, richer Brazilians pay proportionally less tax than the poor and middle classes and the richest 5% earn the same as the rest of the population put together. Yet the highest rate of income tax is just 27.5% .

Markets don’t care much about inequality, but the damaging graft allegations against the president and his allies also threaten to inflict further damage on the country’s institutions.

Temer seems likely to survive this latest crisis – he is expected to win a second vote in the lower house of congress this week on whether to suspend him for a trial – but trust in Brazil’s political leaders has been drastically undermined.

That lack of trust is feeding support for an authoritarian solution to the crisis – which could have serious consequences in next year’s presidential elections.

The lower house of congress first voted not to suspend the president for a trial after Temer was charged with corruption, shortly after his government agreed to spend $1.33bn on projects in the states of lawmakers who were due to vote, according to independent watchdog Open Accounts.

Many of those lawmakers are allied with powerful agribusiness and evangelical Christian lobbies, and face their own graft investigations. Environmentalists say Temer’s administration is reducing Amazon protection in return for their support.

“Our country has been kidnapped by a band of unscrupulous politicians,” former supreme court justice Joaquim Barbosa said afterwards.

Temer has since been charged with obstruction of justice; along with six leading figures from his party, the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, or PMDB, he was charged with racketeering.

Janot has also filed charges against Lula, Rousseff and leading members of their Workers’ party – former allies of Temer’s PMDB – and said both parties were part of a criminal organisation that for 15 years had accepted bribes for decisions relating to ports, airports, droughts, oil rigs, tax breaks and hydroelectric plants in the Amazon.

Former prosecutor general Rodrigo Janot – who unveiled the charges against the three former presidents – said Temer’s party abandoned Rousseff’s governing coalition because it had failed to stop the graft investigation, which in turn led to the lower house of congress approving impeachment proceedings.

“All the members of his criminal organisation, independent of the nucleus they belonged to, had a common interest that united them,” Janot wrote. “The maximum, undue economic advantage for themselves and the others, independent of whether such business attended the public interest or not.”

All of the accused have denied the accusations. Temer has said he is the victim of a conspiracy.

As supreme court justice Luís Barroso told foreign journalists recently in Rio, formidable interests are protecting themselves.

“These people are powerful, they have allies, partners and accomplices everywhere, at the highest echelons, in the powers of the Republic, in the press and where one would least imagine,” he said.

But 78% of Brazilians support the graft investigation. And their disillusionment over the way it is playing out at the highest levels opens a dangerous gap for populists and extremists in next year’s presidential elections.

Lula is seeking a return to the presidency in 2018 – and currently leads polling, but he has been handed nearly a sentence of nearly 10 years in prison for corruption and money laundering, and may well be ruled ineligible to stand.

A likely rightwing candidate is João Doria, the flamboyant, multimillionaire mayor of São Paulo. Like Donald Trump, he is a former host of Brazil’s version of the TV show The Apprentice, only assumed power last January, and has no prior administrative experience.

Running second in many polling scenarios is Jair Bolsonaro, a former army captain whose extreme rightwing, authoritarian message plays well with those angry over corruption as well as voters petrified by Brazil’s soaring levels of violent crime.

And he enjoys the support of a growing number who argue that Brazil’s armed forces should intervene – as they did in 1964, when they installed a vicious dictatorship that lasted 21 years – an option supported by 43% , according to a September online poll.

In September the high-ranking army general Antonio Mourão spooked many when he said that in his view if Brazil’s institutions could not remove those involved in illicit acts from public life, “we will have to impose this”.

Bolsonaro defended him. “Democracy isn’t done by buying votes or accepting corruption for governability,” he tweeted to 602,000 followers. “Reacting to this is the obligation of any civilian or SOLDIER.”