A small company called Rasta Imposta has sued Kmart after the retailer stopped carrying the company's banana costume for the 2017 Halloween season. Kmart switched to another company's banana suit, and Rasta Imposta charges that the rival design infringes its copyright.

But Cornell legal scholar James Grimmelmann is skeptical. Copyright law grants narrower protections to the design of "useful articles" like clothing than it does to traditional creative works like books or movies. Grimmelmann tells Ars it's not clear if Rasta Imposta's fairly pedestrian banana suit design is creative enough to qualify for copyright protection.

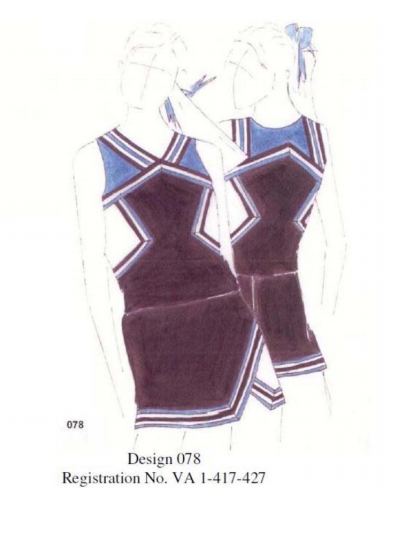

Yet predicting how the case will come out is difficult thanks to a recent Supreme Court ruling on the copyright status of cheerleading uniforms. In that case, which Grimmelmann describes as "a train wreck of a case," the high court ruled that the design of cheerleading uniforms was eligible for copyright protection. In the process, he says, the high court "blew away everything we thought we knew about how useful articles work."

The ruling is widely expected to lead to increased litigation in the fashion industry. Grimmelmann says it's too early to say how it will play out in the market for Halloween costumes. But the Rasta Imposta lawsuit could be the first in a wave of copyright lawsuits over fairly generic Halloween costume designs.

“There is no originality in bananas”

As Bloomberg has reported, this isn't the first time Rasta Imposta has sued over its banana costume. There have been at least two prior cases when the company has sued others for selling similar banana costumes. Both of those cases were settled, so we never got a chance to find out whether they'd stand up in court.

There's reason to doubt they would have. The authors of books, movies, or songs automatically get broad copyright protection. But when you create a useful object like a plate or sweater—or banana costume—the potential for copyright protection is more limited. The functional aspects of an item—like the fact that a sweater has holes for the arms and neck, or the fact that a plate is round and curved up at the edges to hold food—aren't eligible for copyright protection.

Still, creativity can still be protected even when it's embedded in a useful article. For example, Bloomberg points out that the company behind the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers has had some success suing the makers of knock-off Power Rangers costumes.

But those lawsuits succeed because there was significant originality to the non-functional elements of the design—like the brightly colored shapes on the Power Rangers costume. The problem for Rasta Imposta is that the company didn't exactly invent how a banana looks.

"There is no originality in bananas because bananas grow on trees," Grimmelmann told Ars. Elements like a banana's yellow color, tapered shape, or black ends can't be copyrighted because that's just what bananas look like in nature.

If you start with Rasta Imposta's banana costume, peel away functional features, and then also peel away elements that are designed to look like an ordinary banana, there isn't much left. Anyone trying to make a banana costume would wind up making something that looks a lot like Rasta Imposta's design, because that's what bananas look like.

This argument would likely have been more of a slam dunk a year ago. But then the Supreme Court upended how copyright law applies to wearable products.

The defendant in that case, a cheerleading-uniform maker called Star Athletica, had been accused of ripping off uniform designs by industry leader Varsity Brands. Star Athletica said that it had every right to copy Varsity's design because the design served a utilitarian purpose: to signal that the person wearing the uniform was a cheerleader. In Star Athletica's view, separating the aesthetic elements of the design from its purely functional elements wasn't possible. In other words, if you tried to transfer the purely ornamental elements to a canvas, the result would just be a painting of a cheerleading uniform.

This argument convinced the trial court, but the appeals court and then the Supreme Court disagreed. They found that it actually was possible to consider the aesthetic elements of the uniform's design separately from the functional elements—and that these aesthetic elements could be protected by copyright law.

The question here is whether Rasta Imposta's banana design adds enough originality over a generic banana costume to justify copyright protection. It's not an easy argument, but it'll be easier to make now than it would have been before the Supreme Court weighed in.

The larger question is whether other companies will follow Rasta Imposta's lead. "I literally can't tell you what the law of costumes is right now," Grimmelmann said. There's a risk that uncertainty about the law will lead to many more lawsuits in the costume business and the larger fashion industry.

reader comments

80