Growing up in the projects of Baltimore in the 1980s, things like savings accounts, stocks and bonds were completely foreign to Mysia Hamilton. Asked if her parents could have passed along some money to help her buy a car, go to school or put into a house, she can’t help but chuckle.

“No, that wasn’t there. There was no wealth. My mother was working, she was providing – we weren’t on the street begging – but there was no money in terms of ‘here you go’. No money to pass down.”

Now 48, Hamilton is on the path to a different reality. Working as a medical office manager and earning her college degree, the mother of five manages to squelch away $50 a month by furiously clipping coupons and being “extremely frugal”.

“$50 is definitely not my goal, but it’s all I can do with the money that’s going out,” Hamilton said. And it’s working: a decade after she began working with a financial coach, she is on track to have a positive net worth by March 2018. “I’m so driven to do that. It’s important to me.”

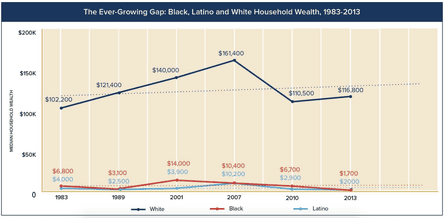

But Hamilton is in the minority, in execution if not intention. A new report calculates that median wealth for black Americans will fall to $0 by 2053, if current trends continue. Latino-Americans, who are also experiencing a sustained downward wealth slide, will hit $0 about two decades later, according to the study by Prosperity Now and the Institute for Policy Studies.

“By 2020, median black and Latino households stand to lose nearly 18% and 12% of the wealth they held in 2013 respectively, while median white household wealth increases by 3%,” the report states. “At that point – just three years from now – white households are projected to own 86 times more wealth than black households, and 68 times more wealth than Latino households.”

With the US set to become “majority minority” by 2044, researchers say this spells major economic peril for the nation. “If the racial wealth divide continues to accelerate, the economic conditions of black and Latino households will have an increasingly adverse impact on the economy writ large, because the majority of US households will no longer have enough wealth to stake their claim in the middle class.”

The authors cite the legacy of discriminatory housing policies, an “upside down” tax system that helps the wealthiest households get wealthier, and the economic effects of mass incarceration as among the root causes for the discrepancy.

“The middle class didn’t just happen by market forces, and the whiteness of the middle class didn’t just happen by market forces. Both were intentional,” said Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, a senior fellow at Prosperity Now and one of the report’s authors.

Take homeownership, which has long been the primary means by which Americans of modest and middle-class income are able to build generational wealth. After the broken promise of “40 acres and a mule” to newly freed slaves, virtually nothing was done to endow black Americans with a share of the wealth generated by centuries of slave labour – the same labour that, directly or indirectly, helped to build most of the wealth enjoyed by white Americans.

So black Americans started off generations behind, only to encounter the redlining and racially restrictive housing covenants of the early-to-middle 20th century, which prevented the sale of many homes to black Americans, and isolated them together in communities that lost value as white residents fled to the suburbs.

“The majority of white Americans weren’t middle class until the 1930s or 40s,” Asante-Muhammad told the Guardian. “Then there was mass investment to create an American middle class – but it was a white American middle class.”

Programs such as the GI bill, which offered returning WWII veterans generous lending terms to buy houses, helped turn the US into a home-owning middle class society – from which black Americans were functionally excluded. In his 2005 book When Affirmative Action was White, Ira Katznelson notes that of the first 67,000 mortgages insured by the GI Bill, fewer than 100 were taken out by non-white people.

Recent economic crises have widened this wealth gap, according to the report, as communities of colour took the brunt of the economic hit. Black median wealth has never recovered from the 2001 recession, nor Latino median wealth from the 2008 financial collapse. White median wealth, on the other hand, was left unaffected in 2002, and began rebounding just two years after the speculative housing bubble began to implode.

“Unfortunately home values don’t come back in the same way in black communities when things happen,” said Althea Saunders-Ranniar, a financial coach and advisor in Baltimore, Maryland, where about 95% of her clients are black.

One of the things Asante-Muhammad and his co-authors found extremely important was focusing on inequality of wealth as opposed to income, because they felt it was a more accurate test of middle-class status.

“You find first-generation, even second-generation African-American and Latino households that have professional jobs and are making ‘middle-income money’ – but they have the wealth of a white high-school dropout,” Asante-Muhammad said. “They’re not truly part of a middle class – which would mean financial stability, money to weather challenging economic situations, or money to invest in the economic opportunities of their children.”

The solution, he said, is to “invest in a 21st-century American middle class. We need to make sure, for the first time, that we are investing in a middle class that includes communities of colour. This generally hasn’t been done before.”

Despite all the institutional and historical barriers, Hamilton remains determined to make the lift – even if those investments never come. “I’m mad because I didn’t start 20 years ago, but it’s OK. I dare not be selfish and not pass this knowledge down to my kids – ones who I know have a chance.”

She hopes to pass more than simply knowledge down, and is on track to come up with a down payment for a modest home by late 2018. “In 20-30 years, even if they still have to pay the mortgage, I can tell them: ‘It’s yours. This is yours.’”

- Share your experiences of wealth inequality, wherever you live, by emailing inequality.project@theguardian.com – or follow us on Twitter here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion