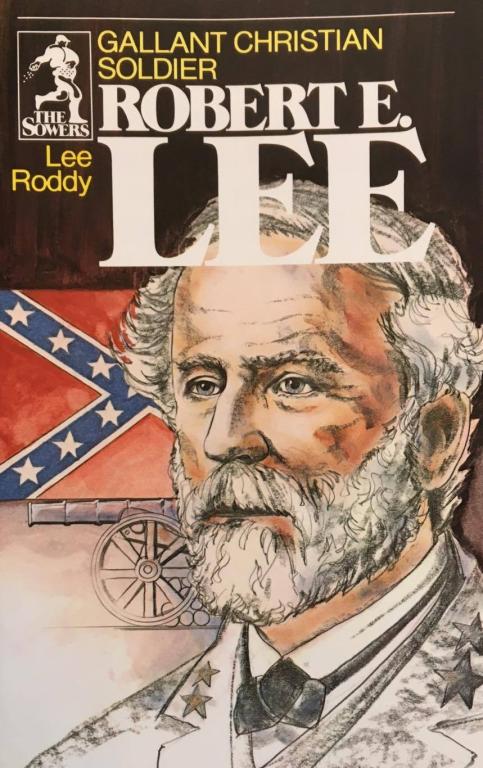

I grew up in an evangelical home, but I must still be somewhat naive about evangelicals and race, because I must confess to being surprised when I came upon this book. Titled Gallant Christian Soldier Robert E. Lee, it was written by author Lee Roddy as part of a series of biographies on men and women of upstanding Christian character.

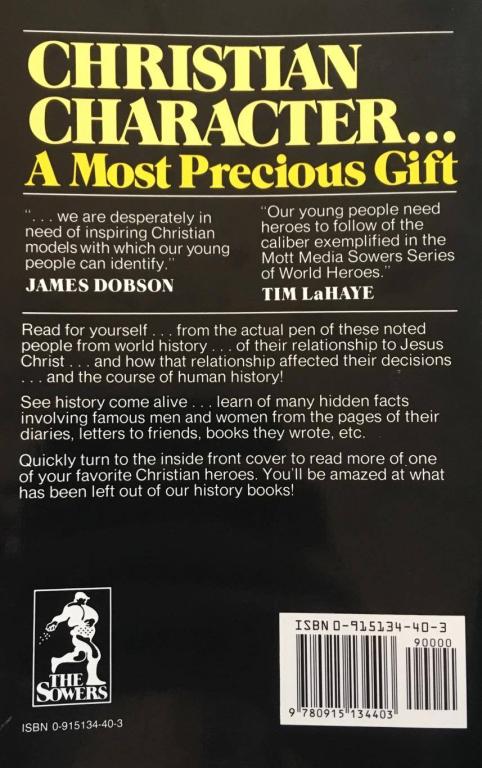

James Dobson and Tim LaHaye were significant figures in my upbringing; while I now disagree with them on a great many issues, it still took me aback to see their names here. Yes, Dobson and LaHaye appear to be endorsing the series and not the specific volume, but that is a distinction without much difference. Their names are here, speaking positively of a Christian character series that includes a volume titled “Gallant Christian Soldier Robert E. Lee.” Either they knew there would be a volume on Lee, or they placed their trust in a series editor willing to commission a volume on Lee.

For those who are curious, this volume was originally published in 1977. Have a look at this excerpt from the forward, by author Lee Roddy:

“Writing about Robert E. Lee has given me an insight into one of the most truly remarkable men in our nation’s history. As a former newspaper editor and writer of countless short historical biographies, I searched diligently for a flaw in Lee’s character. I found none. I cannot say that of any other person I’ve read about or researched.”

I really wish I were making that up. I’m not.

“I confess that I agree with one biographer who wrote, if Protestants had saints, Lee would be one.”

Yes, Roddy really wrote that. And guess what? The book is still be in print. The copy in my hands looks brand new. (I found it in the homeschool library I went through recently, which I mentioned here).

How does the book address Lee’s position as a slaveowner?

Lee had read about the Know-Nothing party and the Free-Soilers. He knew about Free States and Slave States.

His Christmas letter to Mary included references to President Franklin Pierce’s annual message to Congress and a report by the secretary of war. Lee told his wife:

“In this enlightened age, there are few, I believe, but will acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil in any country.” Slavery was a greater evil to the white man than the black, Lee continued. His feelings were “strongly enlisted” on the black man’s side, but “My sympathies are more strong” with the whites.

He thought the blacks’ “emancipation will sooner result from the mild and melting influence of Christianity than the storms and tempests of fiery controversy.”

…

Lee did not approve of slavery, and he saw that “the course of the final abolition of human slavery is onward,” but men could only pray, use “all justifiable means in our power” and trust God to work out the end.

It’s worth looking at this full section of Lee’s letter:

In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil in any Country. It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it however a greater evil to the white man than to the black race, & while my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more strong for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things.

How long their subjugation may be necessary is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence. Their emancipation will sooner result from the mild & melting influence of Christianity, than the storms & tempests of fiery Controversy. This influence though slow, is sure. The doctrines & miracles of our Saviour have required nearly two thousand years, to Convert but a small part of the human race, & even among Christian nations, what gross errors still exist! While we see the Course of the final abolition of human Slavery is onward, & we give it the aid of our prayers & all justifiable means in our power, we must leave the progress as well as the result in his hands who sees the end; who Chooses to work by slow influences; & with whom two thousand years are but as a Single day.

Although the Abolitionist must know this [that slavery will only end slowly over time], & must See that he has neither the right or power of operating except by moral means & suasion, & if he means well to the slave, he must not Create angry feelings in the Master; that although he may not approve the mode which it pleases Providence to accomplish its purposes, the result will nevertheless be the same; that the reasons he gives for interference in what he has no Concern, holds good for every kind of interference with our neighbors when we disapprove their Conduct; Still I fear he will persevere in his evil Course. Is it not strange that the descendants of those pilgrim fathers who Crossed the Atlantic to preserve their own freedom of opinion, have always proved themselves intolerant of the Spiritual liberty of others?

I’m not sure how you can read that letter and come away thinking Lee was anti-slavery. Certainly, he said that slavery would not last forever, and that it would eventually and gradually end. But he also said that slavery was good for blacks, that it was improving their condition, that the ultimate end of slavery must be left up to God, and that it would probably take a very, very long time. He also claimed that abolitionists had no concern in the matter and likened their activity to “interference with our neighbors when we disapprove of their Conduct” and—in fact—claimed that in opposing slavery, abolitionists were being “intolerant of the Spiritual liberty of others.” So there’s that.

Remember, this is a man Roddy claims had a flawless character.

Now, Roddy quotes from Lee’s letter to assert that Lee believed in using “all justifiable means in our power” to end slavery. As you can see at the end of the second paragraph quoted from Lee’s letter above, that statement was positioned in a very mealy-mouthed way. Still, Lee did say it. Did he use all justifiable means in his power to end slavery? Um no.

Have a look at this, from earlier in Roddy’s book:

Lee’s opinion on slavery was suggested in his will, which he made just prior to entering Mexico. It showed he was worth about $38,750 with few debts. His only slaves, Nancy and her children, were to be freed “soon as it can be done to their advantage and that of others.”

But if Lee were truly against slavery, if he truly believed that “all justifiable means in our power” should be put to ending slavery, why not free his slaves forthwith? Why make them wait until after his death?

Here’s another section where slavery is mentioned:

The colonel’s career took a sudden swerve in October when word reached Lee that his father-in-law had died. Arlington’s affairs were in a tangled mess. Lee applied for a two-month’s leave of absence and went home to Virginia.

…

Under the terms of his will, George Washington Parke Custis had left Lee’s wife the great mansion and several slaves. Said Lee of the slaves, Custis “has left me an unpleasant legacy.”

Lee’s position on slavery was already known. His will had specified freedom for his own few slaves. He had allowed other slaves to sail to Nigeria. Now he had his father-in-law’s slaves to handle for a few years. Under the old gentleman’s will they were to be freed within five years.

Bitterness over slavery boiled over onto the colonel on June 24, 1859. The first of two unsigned letters was published in the New York Tribune. The writer claimed to be Lee’s neighbor, but it was obvious the person did not have all the facts about Custis’s will. It was also obvious that the writer did not really know Robert E. Lee.

“All the slaves on this estate, as I understand,” the letter ran, “were set free at the death of Custis, but are now held in bondage by Lee.” The letter said that two men and a woman slave had run away but were caught by an officer and returned. “Col. Lee ordered them whipped,” the letter writer continued. “The officer whipped the two men, and said he would not whip the woman, and Col. Lee stripped her and whipped her himself.” These were “facts as I learn from near relatives and the man whipped,” the first letter concluded. Admittedly, information was not first-hand.

Two days later, the second unsigned poison-pen letter in the Northern newspaper repeated the story.

Lee and those who knew him were aware that he was not capable of doing such a thing. Still, he didn’t defend himself. He wrote his sun, Custis that “the N.Y. Tribune has attacked me for my treatment of your grandfather’s legacy, but I shall not reply.”

Roddy’s de facto assertion that Lee would never have done any such thing is grounded in hagiography. Remember when Roddy declared Lee’s character “flawless”? Roddy’s logic appears to be as follows: A man of flawless character would never whip a slave; Lee was a man of flawless character; Therefore, Lee did not whip a slave. While other historians have pointed out that men of Lee’s rank and status would have been unlikely to personally whip a slave—it would have been considered ungentlemanly—that is not the basis of Roddy’s contention.

What about Custis’ will? Is Roddy’s account of Lee’s work as executor accurate? Let’s take a look. Here are the relevant bits from Custis’ will:

I leave and bequeath to my four granddaughters, Mary, Ann, Agnes, and Mildred Lee, to each ten thousand dollars. …

…

And upon the legacies to my four granddaughters being paid, and my estates that are required to pay the said legacies, being clear of debts, then I give freedom to my slaves, the said slaves to be emancipated by my executors in such manner as to my executors may seem most expedient and proper, the said emancipation to be accomplished in not exceeding five years from the time of my decease.

The trouble was that the slaves on the plantation were under the impression that their master’s will would free them immediately upon Custis’ death. Indeed, the will itself seems to suggest that the slaves should be freed immediately, provided the legacies were paid. However, in sorting through his father-in-law’s finances, Lee determined that there was not enough to pay the legacies—amounting to $250,000 in today’s dollars for each of his daughters—and therefore that the slaves should not be freed immediately.

Believing themselves free, the slaves refused to work. Lee threw the slaves in jail.

Next, Lee petitioned the local court to retain the slaves until their work enough money could be generated for his daughters’ legacies. The court granted Lee’s request, stipulating only that the slaves be freed by the five year deadline. Some of the slaves ran away. Lee had them brought back and (based on testimony from multiple sources) had them whipped (not all sources claim Lee personally did the whipping). Going against his father-in-law’s custom, Lee began separating families in order to hire out individual slaves, to generate money for his daughters’ legacies.

Is it theoretically possible that Lee was bound to uphold the will’s terms, as its executor, and therefore had no choice but to keep the slaves and work them until the money was produced for his daughters’ legacies? I’m not a legal historian, but I could see that being the case. However, a conscientious opponent of slavery who found himself in such a situation could have looked the other way when slaves ran away, rather than dragging them back and having them whipped as Lee did, and would not have had any reason to break up slave families, as Lee did.

There are problems with other details in Roddy’s account, too. Roddy writes that Custis left Lee’s wife with “several slaves.” Perhaps this was a typo, and the word “hundred” was accidentally left out of what should have been “several hundred slaves.” Or maybe it wasn’t so accidental. Next, Roddy claims that Lee told his son that he would not reply to the two anonymous letters. Lee did in fact reply to them. Also, Roddy writes that Lee “allowed other slaves to sail to Nigeria.” In fact, Custis, Lee’s father-in-law, freed the Burke family while he was still living; it was Custis who financed their move to Liberia. Lee neither owned nor freed the Burkes, though his wife did later correspond with Mrs. Burke.

Columbia historian Eric Foner describes Lee as follows:

During his lifetime, Lee owned a small number of slaves. He considered himself a paternalistic master but could also impose severe punishments, especially on those who attempted to run away. Lee said almost nothing in public about the institution. His most extended comment, quoted by all biographers, came in a letter to his wife in 1856. Here he described slavery as an evil, but one that had more deleterious effects on whites than blacks. He felt that the “painful discipline” to which they were subjected benefited blacks by elevating them from barbarism to civilization and introducing them to Christianity. The end of slavery would come in God’s good time, but this might take quite a while, since to God a thousand years was just a moment. Meanwhile, the greatest danger to the “liberty” of white Southerners was the “evil course” pursued by the abolitionists, who stirred up sectional hatred.

After the war, Foner writes, there was more of the same:

Lee claimed that blacks were “not disposed to work,” denigrated their intellectual capacity and expressed the hope that Virginia “could get rid of them.” While claiming to have no interest in politics, he firmly opposed giving black men the right to vote and strongly defended Andrew Johnson’s approach to Reconstruction, which abandoned the former slaves to the mercy of governments controlled by their former owners. A word from Lee might have encouraged white Southerners to accord blacks equal rights and inhibited the violence against the freed people that swept the region during Reconstruction, but he chose to remain silent.

Remember, according to Roddy, Lee’s character was flawless.

This book could have been done very differently (if it had to be written at all). I would have respected a book that portrayed Lee as a man of Christian character who was torn asunder by the sin of racism. A book that showed how a man who believed in the Bible and sought to follow God could find himself so mired sin that he could not see past his own prejudices to the evil he was complicit in perpetrating could have encouraged modern evangelicals to think about their own prejudices, and to consider whether there are any similar sins they are engaging in, but blind to. That would have been a biography of Lee worth reading.

But that is not what this book was. Instead, this book was a hagiography of a perfect Lee who could do (and did) no wrong. Remember, Roddy pronounced Lee’s character literally without flaw. And this was no fringe book. It was produced as part of a series on Christian character endorsed by James Dobson and Tim LaHaye. The people editing this series did not have a problem with including a book on Lee as an example of upstanding Christian character, and they did not send Roddy’s treatment, with his claim that Lee’s character was flawless, back for more work. If this is Christian character, I’m glad I’ve opted out.

Why is this book is still in print? Perhaps we should contact Mott Media and ask. Oh, and if you’re inclined to do so, make sure to ask why the also have a volume titled