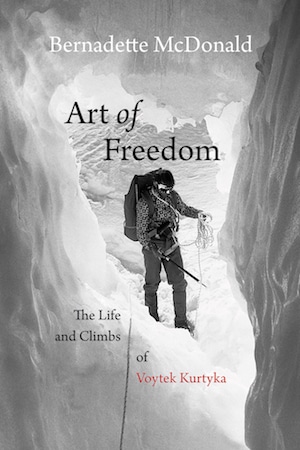

“Alpinism is the art of freedom,” wrote Voytek Kurtyka, the great Polish alpinist who redefined the limits of Himalayan climbing and exploration in the 1980s.

Voytek is perhaps best known for his alpine-style first ascent of the Shining Wall on Gasherbrum IV with Robert Schauer in 1985. Their harrowing ascent had them climbing right at the edge of life and death over days. As details of their experience slowly emerged, the mountaineering community collectively gasped. Their ascent has since been dubbed the “climb of the century.” Over 30 years later, the route itself remains unrepeated. Voytek called the Shining Wall “the most beautiful, mysterious ascent of my career.”

I reached out to Bernadette to hear more about how her book came to fruition. She also agreed to share a couple of excerpts from her book, which in part tells the story of Voytek Kurtyka and Jurek Kukuczka’s first ascent of the southwest face of Gasherbrum 1 (aka Hidden Peak).

Jurek was Voytek’s exclusive partner during the years of 1982-1984, a productive period in which the two climbers climbed Broad Peak’s west face, the southwest face of Hidden Peak, a traverse of Gasherburm East to Gasherbrum II, and a first complete traverse of Broad Peak.

Jurek and Voytek, as we see in McDonald’s excerpt below, had somewhat opposite personalities that seemed to contribute to both their success as well as create occasional conflict. Jurek was aggressive and driven; Voytek prudent and flexible.

They often left Poland without even having enough money to reach their final destination, resorting to clever solutions to reach the Himalaya, where they spent weeks at a time in utter solitude and exultant ascent.

Please enjoy, and be sure to pick up a copy of “Art of Freedom” here.

Why were you drawn to write a book about Voytek?

Bernadette McDonald: During my research for “Freedom Climbers”, my book about Polish climbers, I interviewed a lot of accomplished alpinists. Polish alpinists from that generation were the best in the world. Voytek was one of the most renowned of that group, and his climbs in the Himalaya and the Karakoram were certainly reason enough to focus on him. But a much greater motivation than his climbing achievements was his way of thinking. Voytek is a highly intelligent, constantly searching, endlessly curious individual, and his thoughts and attitudes about climbing, life, love, spirituality, and friendship were intriguing. He is also an extremely private person, so the effort of trying to understand him was an appealing challenge. All of these were contributing factors.

Bernadette McDonald: During my research for “Freedom Climbers”, my book about Polish climbers, I interviewed a lot of accomplished alpinists. Polish alpinists from that generation were the best in the world. Voytek was one of the most renowned of that group, and his climbs in the Himalaya and the Karakoram were certainly reason enough to focus on him. But a much greater motivation than his climbing achievements was his way of thinking. Voytek is a highly intelligent, constantly searching, endlessly curious individual, and his thoughts and attitudes about climbing, life, love, spirituality, and friendship were intriguing. He is also an extremely private person, so the effort of trying to understand him was an appealing challenge. All of these were contributing factors.

During this process, what did you learn about Voytek that was surprising?

BM: There were a number of surprises. Although I knew that he wasn’t a religious person, I was surprised at the vehemence of his disdain for traditional religious practices and, in contrast, his deeply spiritual nature. And although I also knew that he was an extremely creative person, I was astonished at the complexity of his ruminations on creativity and the importance of it to his life—and in his view, all life. Finally, the depth of his feelings for his climbing partners, the joy and the pain of those relationships, was quite revealing.

Why is Voytek’s biography important to read now, in 2017?

Voytek’s story is unique because it’s about Voytek, but the struggles and challenges and life-changing decisions that he has had to make, based on what life’s circumstances placed in front of him, are relevant to all of us. He grew up in challenging political times, in difficult financial situations, with complex personal relationships. He experienced both failure and success; he felt sorrow and joy; he made some great life choices and some that brought him pain. But he never lost his appreciation for the beauty that can be found everywhere; even, as he puts it, in the weeds by the side of the road. There is something hopeful about that.

“Lost and Found on Hidden Peak”

An excerpt from Bernadette McDonald’s new book “Art of Freedom“

Voytek’s plan for the Gasherbrums wasn’t turning out as he had intended.

The 1983 trip was meant to be with both Alex MacIntyre and Jurek Kukuczka, to create a remarkable trio of complementary characters. Voytek had always marveled at Alex’s imagination in the mountains, as well as his pre-climb strategy: drink heavily the night before. Alex seemed to approach all the great events in his life with a hangover, reasoning that the mass destruction of brain cells prior to climbing at altitude left fewer of them to be destroyed by the absence of oxygen during the climb. Voytek took such delight in Alex and his crazy ideas.

They had shared a lot in the mountains. “For Alex and me, alpine style meant a way of life and a state of consciousness that allowed us to fall in love with the mountain and, in consequence, to trust our destiny to it—unconditionally.”

Voytek had even written about Alex’s unique qualities in Mountain magazine: “Will I ever see you again? Oh yes, in a week I’ll see Alex with all his dominating tranquility and confidence, which, when I look back through my mountains and even more through my anxious returns to the plains, I was always so lacking and longing for. I’ll see him again and he’ll make me believe for a while that I can seize this tranquility again.”

When Alex was killed on Annapurna, struck by a falling stone, the expedition dwindled to two: Jurek and Voytek. But this unlikely pair was a formidable team. They had already proven themselves on Makalu and Broad Peak. They managed to coexist for weeks in the Himalaya, like an “old, comfortable couple”, as other climbers observed. They shared small tents on their airy bivouacs, cooked and ate together, and managed the stress of altitude and risk. Voytek was the “idea guy”, whereas Jurek brought confidence and strength. They never seemed to talk but always seemed to be in touch.

Voytek laughed as he reflected on their differences. “When I was in pain all over, I would notice Jurek showing some small signs of suffering. When I was already deeply afraid, Jurek still did not feel any fear for a long time. When I experienced dreadful fear, Jurek was only slightly worried.” Voytek’s meticulous planning and strategy balanced Jurek’s more spontaneous and aggressive approach. Voytek’s slender frame and his technical climbing skills complemented Jurek’s remarkable strength and endurance. “Jurek was the greatest psychological rhinoceros I’ve ever met among alpinists, unequaled in his ability to suffer and his lack of responsiveness to danger,” Voytek said. “At the same time, he possessed that quality most characteristic to anyone born under Aries—a blind inner compulsion to press ahead. Characters like that, when they meet an obstacle, strike against it until they either crush it or break their own necks.” Those who observed them in the mountains called their partnership “magical.”

Gasherbrum II, 8,034 meters, Karakoram, Pakistan. New route on the South-East Ridge, alpine style, by Voytek Kurtyka and Jerzy Kukucka in 1983. Voytek Kurtyka collection; route outline by Piotr Drozdz

The Gasherbrum group comprises six peaks encircling the South Gasherbrum Glacier in Pakistan’s Karakoram mountains. Gasherbrum I, sometimes known as Hidden Peak, is the highest of the six peaks, at 8,080 meters. It was first climbed in 1958 when Nick Clinch led an American team to the summit. Afterwards, border disputes between India and Pakistan closed the area to expeditions for many years. Then, in 1975, Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler made an alpine-style ascent of Gasherbrum I, without supplemental oxygen, and established a new standard in Himalayan climbing. The same year, Wanda Rutkiewicz led a team up 7,946-meter Gasherbrum III, making a first ascent of the highest unclimbed peak in the world at that time.

Gasherbrum II, the second highest in the Gasherbrum group, at 8,034 meters, is an even more angular piece of geometric perfection than Gasherbrum I and was first climbed in 1956 by an Austrian team. Voytek and Jurek were going to the Karakoram for both Gasherbrum I and Gasherbrum II. And they intended to climb them both by new routes.

They arrived at the India–Pakistan border, their truck fully loaded with barrels of food and climbing equipment. Hidden among all this was an illicit cargo of thirty-six bottles of whisky, which they planned to sell. They knew the routine: roll up to the border, breeze through Indian customs, drive through a 200-meter no man’s land, unload the trucks, reload the barrels into a Pakistani truck and, finally, pass through Pakistan customs.

Voytek had spent long, tedious hours packing the hidden contraband in the barrels. “We were in a cheap hotel and the temperatures were high,” he said. “There was no air conditioning, only a fan. We were sweating like wild dogs. Really horrible. So it wasn’t easy to pack them. I painstakingly put every bottle either in a sleeping bag or in a bag stuffed with socks and soft clothing. Then I placed them at the bottom of the barrels.” Most of the barrels were “clean,” but three contained twelve bottles each. Jurek had watched in amusement (and with some impatience) while Voytek swaddled the precious bottles and distributed them among the three barrels, all carefully marked for easy identification and placed at the back of the load, should there be any problems at the border. They weren’t concerned about getting out of India; it was entering Pakistan that might be tricky.

Voytek Kurtyka and Jerzy Kukuczka Gasherbrum 1 base camp in 1983. Voytek Kurtyka collection.

Their truck crawled up to the Indian border crossing. It was a sultry day; the sun hung heavy in the muted sky. The Indian customs agent was suspicious and surly. They were stunned when he ordered them to unload the truck for inspection. Voytek protested. “Come on. We are leaving your country, not entering it.” The agent mumbled something about just following orders. After a somewhat cursory glance into the top of each barrel, he ambled over to his commanding officer and reported that all seemed okay. The officer snapped at him, accused him of shoddy work and insisted he do it all over again.

Voytek and Jurek had already reloaded the barrels but now realized that the inspection was not over. Voytek’s hands were sweating, and Jurek felt queasy. Whisky was not considered “necessary food provisions”, and it certainly didn’t qualify as climbing equipment. Jurek walked around the front of the truck, sat down on the ground and lit a cigarette. Traveling with them to base camp was a trekker; the man walked off in terror, convinced he would spend the rest of his life in an Indian jail. To calm himself, he had some tea.

Voytek refused to help the border agent. “I was thinking, no, I will not help them. ‘Sorry, sir, it is very hot. It is too much for us. Open them yourself.’” The forty-something, balding agent opened each barrel in the first row and inspected the contents piece by piece. “He was ruining my packing job,” Voytek remembered. “I thought he would give up after a couple of barrels. It was more than 40 °C and he was sweating like crazy.” When the inspector finished the first row, Voytek began to repack the entire mess, confident that the ordeal was done.

“Next row, please,” announced the inspector.

Trying to hide his impatience, Voytek remained calm and answered,

“Of course. Please, enjoy.” He described the scene: “I noticed that Jurek was now on cigarette number three. The trekker was on his third cup of tea. I was sweating and the customs guy was dripping.”

“Next row,” demanded the agent.

“Really? If you want it, go ahead,” Voytek gasped, throwing up his hands in frustration. Piece by piece, the customs agent examined the barrels in row three. Then he demanded row four.

Directly behind row four was guilty row five. “I knew what was in it,” Voytek recounted. “What to do?” He came up with a risky scheme to surreptitiously exchange the row-five barrels with the already-inspected barrels sitting outside the truck. He became helpful again, hoping to confuse the agent with his eager co-operation and to bury him in senseless details. “I began explaining things to him. These are shoes, this is a stove, a sleeping bag, these heavy tins are meat.” During all this, Voytek managed to slip one of the “dirty” barrels to Jurek to place outside. Incredibly nervous, Jurek returned to the front of the truck to smoke. He knew there were only two barrels left in the truck and they were both dirty. Puff. Puff. Puff.

Voytek turned back to help the customs agent. “I was taking out the sleeping bag wrapped around the whisky. I carefully placed it down on the truck so it didn’t clink like glass. I explained to him that this was my clothing; this was my equipment.” The agent nodded in approval and moved on to the last barrel. Voytek was so tense he felt ready to explode. The veins on his forehead bulged as he lifted each sleeping bag packed with whisky as if it were a newborn child wrapped in swaddling clothes. Gently, almost tenderly, he removed the sacks of heavy socks and climbing pants, all hiding whisky.

Miraculously, the bundles remained intact.

He glanced around at Jurek and saw that his package of cigarettes was finished and his face looked slightly green. The trekker, his face flushed, was completely out of tea. The weary customs agent declared the inspection over and staggered off.

They reached base camp at 4 p.m. on 3 July 1983, having completed the first traverse of Gasherbrum II, and the first traverse of multiple peaks at that altitude—all done in alpine style. Voytek explained why it had been so appealing: “A high-altitude traverse is the essence of adventure. You can hardly invent a more unpredictable kind of venture in alpinism.” They felt in top form to tackle Gasherbrum I.

Voytek and Jurek settled in to wait for good weather. They waited some more. Twenty days of snow and cloud. Their only entertainment was the purple-black ravens circling overhead and begging for food. Voytek was eager to maintain good relations with the ravens, and they were swimming in extra food, thanks to the Swiss. So he fed them. The ravens seemed particularly fond of noodles and ham, but they waddled away in disgust from any offerings of porridge or cornflakes. As the good news spread, ravens arrived in flocks, hopping around camp with their ungainly stagger, squawking to each other and waiting for their daily treats. Voytek would take out a three-kilogram tin of Polish ham, cut it into pieces and toss them out to the ravens, who would swoop in and grab them. The birds were so greedy for the ham that they almost choked on it. It was a great diversion and helped pass the time. Voytek felt a strong connection to those beautiful and intelligent birds.

But Jurek wasn’t happy. “Voytek, I know you are not listening to me, but I can’t watch what you are doing,” he complained. “I know we don’t need this ham, but to treat the food like this, to throw it to the birds, this is not the proper way. This is wasting food.”

“But Jurek, we have so much food. There is no better way,” Voytek responded. “Do you want to leave it here to rot? The Pakistanis won’t take this ham. You know they won’t. It’s against their religion.” Jurek understood the logic, but he was troubled by Voytek’s lack of respect for the food. Particularly the ham. Voytek relented and stopped throwing ham. The ravens waited, staring at him. The boredom grew. Eventually, the two climbers retreated into their respective tents. Voytek read. Jurek slept. They emerged for meals together and waited for the weather to turn.

Porters on the way to the Gasherbrums in the Baltoro, 1983. Voytek Kurtyka.

One day British climbers Doug Scott and Roger Baxter-Jones arrived for a visit. They were climbing over on K2 and needed some company while they waited out the storms. Voytek and Jurek were happy to accommodate them, whipping up fine meals of odd combinations from the Swiss and Polish food supplies: sardines with cheese sauce, chocolate fondue, bacon with potatoes. When the British guests left, Voytek and Jurek were left to themselves again. They took turns preparing meals, and the increasingly complex and bizarre menus became the focal point of each day. Despite all the good food, Jurek was losing weight. In contrast, Voytek was gaining weight, losing his edge. He felt as heavy as a sack. He would need a few hunger days once the climb was over to regain his desired strength-to-weight ratio. “Spending a lot of hours in the kitchen,” Voytek wrote in his journal.

The snow and rain continued.

When Voytek first wrote about those long weeks in camp, his words sometimes expressed deep despair. “Totally alone and isolated on our moraine we suffered twenty days … empty and dreary days.” But there is a flip side to bad weather that most climbers, including Voytek, will acknowledge: meditative days spent relaxing with little stress. “Learning a language, reading, trying to think about writing, literature, but not a single beautiful sentence comes to my head … thinking about home … ” he wrote.

When they could no longer tolerate the inaction, Voytek and Jurek carried supplies over to the base of the face of Gasherbrum I. They had just dropped their loads and were about to turn back to base camp when a horrifying, muffled sound emerged from the mountain. They watched as two enormous ice avalanches swept down the entire length of the face and across the cwm to the foot of their intended route. Clouds of snow billowed up like an atomic explosion. Then the mountain lay silent, dusted in white. Shaken, they trundled back to camp, where the memory of the avalanches conjured up alarming visions of suffocation, falling, burial, death. Voytek’s journal revealed his dark thoughts: “Air pressure falling. Today I’m thinking more about descending than climbing. Fearing the wall. I’m afraid of the lower cwm. Giving up.”

On 17 July the air pressure soared, the temperature dropped and the sky cleared. Their optimism soared, too, but despite the good weather, they were on high alert, psychologically and physically. Voytek and Jurek spent the next day fretting. There was so much to consider: the deadly cwm, the treacherous snow conditions, the avalanche hazard and the summit rock barrier. On 19 July they woke at 2 a.m. The stars were obscured by cloud, and it was warm (–3 °C) and a bit windy. They gave up and returned to their tents. When they woke up later that morning, the sky was bright and clear, with perfect visibility. The temperature had cooled and the air pressure had risen. In other words, the conditions for climbing were perfect. To ease their guilt at not having started earlier that morning, they broke trail through the snow to the foot of the wall, saving time for the next day.

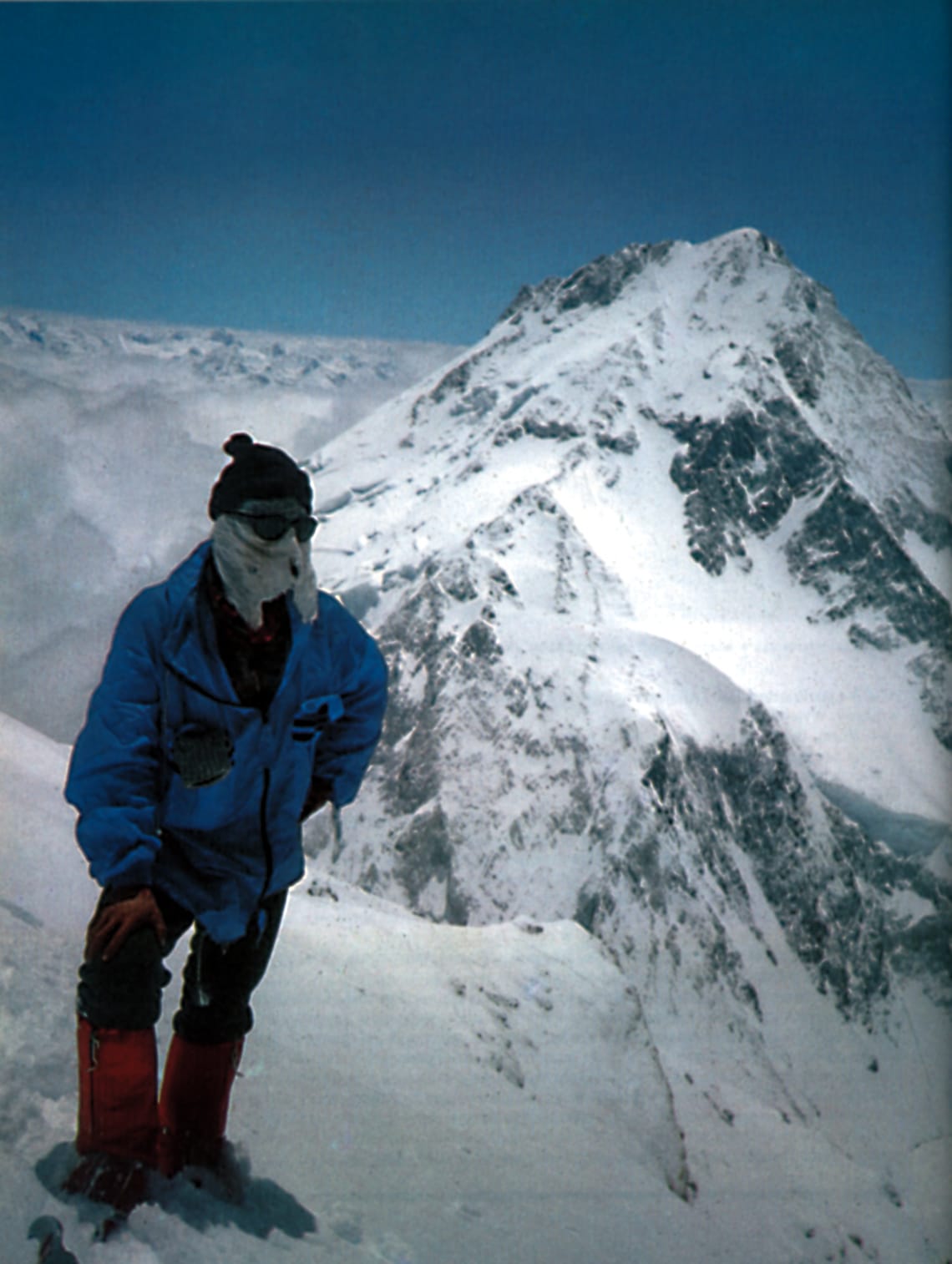

Voytek Kurtyka approaching the rock barrier on Gasherbrum I on the first day of the climb. Jerzy Kukuczka, Voytek Kurtyka collection.

Excited and anxious, they considered their options. In only two days the porters would arrive to break camp and carry their equipment down. Could they climb Gasherbrum I by a new route and descend to base in two days? Definitely not. Leaving their camp unattended was risky; they both knew that. And if the porters arrived at an empty camp, they would likely assume the climbers had been killed on the mountain. They would leave, and Jurek and Voytek would be stuck with all their gear, or worse, without any gear at all, depending on the porters’ moral compasses.

Voytek hustled over to his tent and hunted among his books and papers.

He grabbed the largest piece of blank paper he could find, marched away from the tent and studied the face. He sketched a rough drawing of the mountain and then placed two stick climbers on the face with arrows pointing to the summit. Surely the porters would understand this. No, he shook his head in frustration; it wasn’t clear enough. He added five more stick figures at base camp with arrows pointing to the kitchen tent. Now they would understand that they were supposed to stay and wait, using the kitchen tent for shelter. Confident that the message would be clear, Jurek and Voytek placed a large rock on the drawing, carefully buried their passports and money, and loaded their packs.

They set out at 3.15 a.m. on 20 July. At 5.30 they arrived at the base of the cwm. No ice avalanches, no snow avalanches, not a breath of wind. The silence felt ominous. They stared up at the ice cliffs and towering séracs leaning above the cwm that they needed to traverse. Voytek later described their decision: “We switched off our brains and moved steadily into danger. Ten minutes later we emerged.”

Starting up on steep snow and ice, they soon encountered a rock barrier that blocked access to the upper mixed ground of the summit wall. They called it the Fork. Up until now they had made good progress, but this pitch of grade V slowed them down. The next morning they emerged into a dazzling scene of snowfields and towering ice séracs. The sun hammered down. The silence deafened. They tested the snowpack with one foot, then another. It was inconsistent, collapsing in places, holding firm in others. To avoid the huge, unstable wall of snow, they moved closer to the left-hand pillar, where their crampons scratched against the rock. It was impossible to develop a rhythm on this awkward terrain. Still, their spirits were high, and Voytek felt as free as the ravens playing in the thermals overhead. He felt encouraged by the ravens – almost protected. Voytek and Jurek tunneled and navigated a route up through the sérac barrier until they reached around 7,200 meters, where they found a reasonable spot for a bivouac. Tomorrow would be summit day.

Voytek Kurtyka on the summit of Gasherbrum II East, 1983. Photo: Jerzy Kukuczka.

They arose at 2 a.m. on 22 July, cooked two pots of tea and crawled out of the tent at 5.30. The miraculously calm weather was holding. A pastel dawn crept across the upper slopes of the mountain while the valleys below remained cloaked in darkness. After crossing the upper snowfield, they reached the greatest unknown of the entire climb: the highest rock barrier. They opted for a line slightly right of center but neither felt confident it would go. After just one pitch of climbing, they knew they wouldn’t finish before nightfall. Frustrated, they stopped and set up a rappel to return to their last bivouac. Jurek went first. When he was down and off the first rappel, Voytek began. Suddenly he heard Jurek cursing loudly. Voytek glanced down and, out of the corner of his eye, spied one of his own crampons tumbling down the slope. Disaster! They limped back to the bivouac, Jurek belaying Voytek most of the time and Voytek relying on a single crampon for security.

Once at the bivouac, the severity of their situation set in. They were high on the South-West Face of an 8,000-meter peak. Steep, complex terrain lay between them and the base of the mountain, and downclimbing it with one crampon was a terrifying prospect. The summit was within reach, but that would require even more finesse. And to add to the stress, they knew the porters were probably already at base camp, waiting for them. Unexpectedly, Jurek offered a solution that seemed to completely ignore their precarious situation but that appeared reasonable enough to him. “We can get to the top tomorrow by traversing to the right to the South Ridge,” he assured Voytek.

“With one crampon? I don’t think so.”

“Hmmm, that’s a problem, all right. Well, I’ll go to the summit alone. You can stay here and wait for me. No problem. I’ll take the rope with me to the summit and then tomorrow we can go down. I’ll help you with the descent.”

Voytek couldn’t believe what he was hearing. Jurek was going to leave him at 7,200 meters on the South-West Face of Gasherbrum I with one crampon and no rope. What if Jurek fell? He would be abandoned on the mountain with no way of escaping. As the hours passed in their little tent, Voytek’s emotions vacillated from annoyance to bitterness to a sense of total abandonment. Finally, feelings of anger emerged to help him make the final decision. If he was going to be abandoned here, he would rather die in an even more dangerous situation, but at least together with his partner. He calmed himself and announced, “No way, Jurek. I’m not staying here alone. Okay, if you want the summit so badly, I’m coming with you.” Jurek shrugged his agreement.

They rose early the next morning and began traversing much lower than their previous line. Jurek was out front. Suddenly Voytek heard an alarming scream. He yelled up. “What?! What happened, Jurek?”

“I found it. Your crampon. It’s here.” Jubilant cursing followed as Voytek caught up to him and reattached the precious crampon. It had fallen around 500 meters but had miraculously caught in the snow. Fully cramponed now, they angled over to the South Ridge and continued up the steep, rocky and confusing terrain, which was partially covered with loose, unconsolidated snow. They reached the summit at 2.30 p.m.

Great read! Love the story of the lost and found crampon. Those guys were the real deal!