The Invisible Poems Hidden in One of the World's Oldest Libraries

A new technique is revealing traces of lost languages that have been erased from ancient parchments.

For centuries they have gathered dust on the shelves of a library marooned in a rocky patch of Egyptian desert, their secrets lost in time. But now a collection of enigmatic manuscripts, carefully stored behind the walls of a 1,500-year-old monastery on the Sinai Peninsula, are giving up their treasures.

The library at Saint Catherine’s Monastery is the oldest continually operating library in the world. Among its thousands of ancient parchments are at least 160 palimpsests—manuscripts that bear faint scratches and flecks of ink beneath more recent writing. These illegible marks are the only clues to words that were scraped away by the monastery’s monks between the 8th and 12th centuries to reuse the parchments. Some were written in long-lost languages that have almost entirely vanished from the historical record.

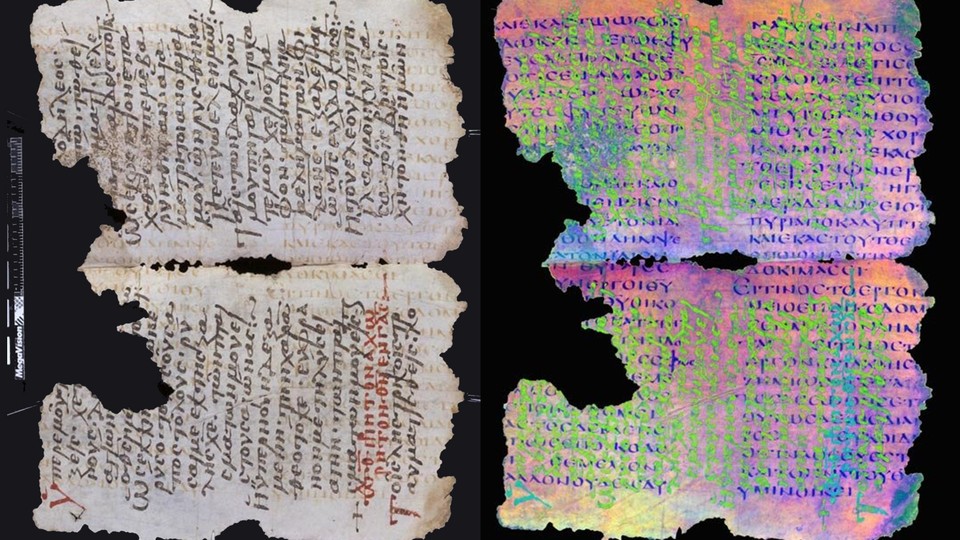

But now these erased passages are reemerging from the past. In an unlikely collaboration between an Orthodox wing of the Christian faith and cutting-edge science, a small group of international researchers are using specialized imaging techniques that photograph the parchments with different colors of light from multiple angles. This technology allows the researchers to read the original texts for the first time since they were wiped away, revealing lost ancient poems and early religious texts and doubling the known vocabulary of languages that have not been used for more than 1,000 years.

Isolated at the mouth of a precipitous gorge at the foot of Mount Sinai—a mountain sacred to the Christian, Islamic, and Jewish faiths—Saint Catherine’s Monastery has persisted relatively unscathed since the sixth century. Its library was famous as a center of learning even its very earliest days, and the tinder-dry climate has helped to preserve the delicate parchments.

At times in the past, however, the monks found themselves stranded without fresh supplies. The rise of Islam in the seventh century saw almost all of the other Christian sites in Sinai disappear, leaving the fortified monastery at Saint Catherine’s far harder to reach. Tensions between the Muslim world and Christians during the Crusades also made pilgrimages to the monastery more sporadic. Scribes were often forced to reuse older parchments, each composed of hundreds of pages. They would carefully wash them with lemon juice and scrape them clean of text. The scribes chose older texts—some dating as far back as 600 AD—whose language had been forgotten or whose information was no longer relevant.

Today, these parchments are delicate gold mines of historical importance. Scholars studying the early scriptures of the Christian faith, historians looking for clues about life in Medieval Egypt, and linguists searching for scraps of ancient languages have all pored over the parchments. In the margins, some parts of the older under-texts have remained visible, giving some clues to the content beneath.

To reveal the erased words on the palimpsests, the researchers photograph each page 12 times while it is illuminated with different-colored visible light, ultraviolet light, and infrared light. Other images are taken with light shining from behind the page or off to one side at an oblique angle, helping to highlight tiny bumps and depressions in the surface. Together, these photographs help reveal the minute traces of ink left on the pages after they were erased or the scratches left by a scribe’s quill. Computer algorithms then analyze and combine the images so the text on top can be separated from the words below.

Over five years, the researchers gathered 30 terabytes of images from 74 palimpsests—totaling 6,800 pages. In some cases, the erased texts have increased the known vocabulary of a language by up to 50 percent, giving new hope to linguists trying to decipher them. One of the languages to reemerge from the parchments is Caucasian Albanian, which was spoken by a Christian kingdom in what is now modern day Azerbaijan. Almost all written records from the kingdom were lost in the 8th and 9th century when its churches were destroyed.

“There are two palimpsests here that have Caucasian Albanian text in the erased layer,” says Michael Phelps, the director of the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library and leader of the project. “They are the only two texts that survive in this language ... We were sitting with one of the scholars and he was adding to the language as we were processing the images. In real time he was saying ‘now we have the word for net’ and ‘now the word for fish.’”

Another dead language to be found in the palimpsests is one used by some of the earliest Christian communities in the Middle East. Known as Christian Palestinian Aramaic, it is a strange mix of Syriac and Greek that died out in the 13th century. Some of the earliest versions of the New Testament were written in this language. “This was an entire community of people who had a literature, art, and spirituality,” says Phelps. “Almost all of that has been lost, yet their cultural DNA exists in our culture today. These palimpsest texts are giving them a voice again and letting us learn about how they contributed to who we are today.”

Other palimpsests are written in more common languages like Arabic, Syriac, Latin, and Greek. More than 108 pages of previously unknown Greek poetry were uncovered beneath more recent Arabic and Georgian texts. Three previously unknown Greek medical treatises have also been found, including one that contains the oldest known recipe credited to Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine.

For classical and medieval scholars, the ability to read these lost texts has brought new energy to their field. “This new project has brought a 25 percent increase in the readability [of the Caucasian Albanian palimpsests],” says Jost Gippert, a linguist at Frankfurt University who has been studying Caucasian Albanian for more than a decade.

Phelps and his team are making their findings publicly available online so scholars around the world can study them. It is a timely effort: Recently Saint Catherine’s, which is controlled by the autonomous Church of Sinai, part of the Eastern Orthodox Church, has come under threat from nearby attacks by groups affiliated with the Islamic State. “A big piece of what we are doing is making sure future generations have access to this material despite the geopolitical pressures,” says Todd Grappone, an associate librarian at the University of California, Los Angeles, and another member of the research team.

Some of the palimpsests that the team has recovered, however, suggest the tensions between Islam and Christianity were not always so fraught, and highlight the role the monastery played as a meeting point for the faiths. “We are recovering the history of the monastery from a time when there are almost no historical records,” says Father Justin Sinaites, a Texan who has been the librarian at Saint Catherine’s for the past 10 years and is charged with protecting its parchments. Many of the texts indicate an exchange of ideas and literature between the faiths, with early translations of Christian scriptures and liturgies into Arabic appearing in the palimpsests.

“We are finding evidence of how important texts reached the Arabic-speaking world in the first centuries of Arab rule,” says Sinaites. “I don’t think you can understand the problems in the world today without understanding the history of this part of the world.”