In November 2015, a much-publicised process of crowdsourcing ideas and putting them to a vote culminated in the city of Seoul unveiling its current English-language slogan: “I.Seoul.U.” It met with more ridicule from the local English-speaking community than most of the South Korean capital’s international PR moves (including, but hardly limited to, photoshopped versions for the long-suffering village of Fucking, Austria).

“The arrogance, the vitriol and the self-appointed expertise evident in this explosion of online bile is extraordinary,” wrote Korea Times columnist Andrew Salmon as he surveyed the announcement’s aftermath. He argued that “the obvious, natural focus for Seoul tourism promotion is China and Japan”, and that “the stark simplicity of I.Seoul.U may well speak to tourists hailing from these high-potential target markets [who have], on the whole, a poor command of English”.

Furthermore, the unconventional, offbeat, and quirky strapline, as he described it, puts it alongside the Nike “swoosh” and legendary graphic designer Milton Glaser’s “I ❤ NY” – both “classic exercises in branding” exerting abstract emotional appeal.

Indeed, I.Seoul.U was seen as a step forward in Seoul’s branding. Whatever its innate strengths or weaknesses, the slogan has brought more attention to a city that has long suffered image problems. For most of the 65 years since its emergence from the destruction of the Korean War, both Seoul and South Korea in general have struggled to define themselves on the cultural world stage, despite going on to become one of the most impressive economic success stories in human history.

The most relevant comparison in success is to the country’s neighbour and former coloniser Japan. In a period of about 30 years Japan “moved out of its negative image to become one of the most admired countries in the world”, in the words of place-branding consultant Simon Anholt.

“Korea’s image is improving, because Korea is improving,” he said more recently. “It’s getting richer and more confident,” yet its officials continue to self-defeatingly insist on “constantly publicising the fact they want a better image”.

Anholt believes “impatience, a lack of objectivity, boring strategies, faulty leadership, a naive faith in the power of propaganda, and a desire for quick fixes and short cuts”, are among the most common obstacles to proper nation branding; and for all the strengths of the country itself, South Korea still occasionally falls victim to these vices. Just last month it scrapped its English-language national brand “Creative Korea”, developed last year at a cost of $3m, amid accusations of a lack of creativity and, given France’s previous use of the brand “Creative France”, of plagiarism as well.

Japan may have a higher profile than South Korea, but not every branding scheme has been a work of genius. Around the same time as I.Seoul.U, the Japanese capital rolled out its own awkward quasi-English slogan “& Tokyo”. Yet whereas the nation of Japan and the city of Tokyo maintain two related but essentially independent public images, South Korea can’t be discussed apart from Seoul quite so easily. Half of the entire country’s population lives in the 25 million-strong Seoul metropolitan area, and South Koreans from other regions have continued to regard Seoul as the only place affording real opportunity.

To a great extent, Seoul is Korea and Seoul’s image is Korea’s. The country and the capital have developed in tandem, and the inextricability of those two processes lies at the heart of Korean architecture professor Jieheerah Yun’s recent study Globalizing Seoul. Yun assesses the historically inward-looking city’s efforts to turn outward, presenting itself no longer as an “industrial ‘hard city’ emphasising speed and efficiency”, but as a “soft city”, one that values “the appreciation of invisible things, such as cultural and emotional wellbeing” – prioritising aesthetics as well as economics.

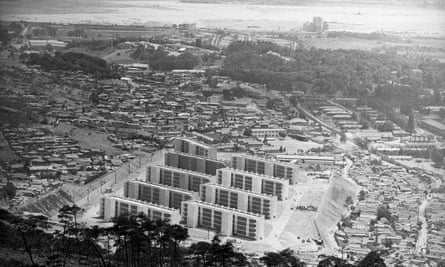

The idea, she writes, has been to move away from the “development dictatorship” that produced a monotonous, hastily constructed concrete-and-steel metropolis filled with lookalike office buildings and apartment towers (also plagued for a time with disasters, most tragically the 1995 collapse of the Sampoong department store) towards a more participatory process to remake Seoul as a “versatile ‘cultural’ city filled with tangible and intangible resources”.

In the past 15 years many urbanist-celebrated projects have popped up based on these rather abstract notions. There is Cheonggyecheon, a life-filled stream running through downtown Seoul where an elevated freeway once stood; the Dongdaemun Design Plaza (DDP), an unearthly metallic museum and shop complex designed by the late Zaha Hadid placed in the centre of a busy market neighbourhood; and most recently Seoullo 7017, an overpass turned urban park that has been compared with Manhattan’s High Line since opening in May.

Yet this publicity also provided a chance for the media to once again highlight the sources of Seoul’s inferiority complex: “Built up quickly during the country’s astonishingly fast industrialisation,” wrote the Washington Post’s Anna Fifield, the city has “often been derided with the saying, ‘There’s no soul in Seoul’”.

The official branding work meant to counteract that image goes back a decade when the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design selected Seoul as its “World Design Capital” for 2010. The local government soon launched the Design Seoul campaign as an effort to “elevate Seoul to the hub of the world design industry”, thereby introducing the English term “design” into the mainstream Korean lexicon.

It has since turned into an all-encompassing catch phrase, according to Yun, or in the words of one member of activist artist collective FF Group: “A master key that can be used for anything,” including the justification of questionable or undemocratic policies.

That ambiguous buzzword certainly did its part to push through the construction of the DDP, a successful quasi-public space as well as a costly infusion of foreign prestige that, not without controversy, replaced an old sports stadium and flea market grounds.

The DDP’s early promotional materials made explicit comparisons to Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and its supposed economic and cultural revival of the post-industrial Spanish city. The buildings do have much in common, especially a similarly tenuous connection to the cities that surround them.

Yun quotes architect and branding scholar Anna Klingmann, warning that these potentially “short-lived images of dazzling signature projects” produce “a culture of the copy, imitating one another in their offerings and aesthetics”. It remains to be seen whether the DDP, which opened in 2014, will ultimately attain international recognition an icon of Seoul.

In 2012, with the DDP still under construction, a very different cultural project had already turned into a global phenomenon, spreading an image of the city to every corner of the world: Gangnam Style. No official branding effort, however well-meaning or well-funded, could have hoped to reach as many people across the world as the singer-rapper Psy’s mesmerisingly odd music video – which for years was the most viewed on Youtube.

Psy’s song and video satirises the boastful, free-spending, strenuously westernised and usually heavily indebted lifestyle associated with the capital in general, and Gangnam in particular – an area that developed far later than north of the river Han.

“As late as the 1970s, most of the Gangnam area was rice paddies or agricultural fields,” writes Yun, “but it did not remain undeveloped for long.” As the government built bridges and rail lines across the Han River, relocated important institutions and elite schools to the south, and offered tax incentives to developers, Gangnam became the popular place to live, with house prices rising and “producing numbers of nouveau riche who became rich through real estate speculations”. Land prices north of the Han increased 2,500% from 1963 to 1979 – not a bad profit, except that those in Gangnam increased between 80,000-130,000% over the same period.

When Gangnam Style exploded, the mighty Korean pop culture industry had been hard at work for almost 15 years. But the appeal of this so-called “Korean wave” of melodramatic TV and glossy music videos proved primarily aspirational, mostly washing over Korea’s Asian neighbours and hardly lapping the shores of the west.

Busy grooming squadrons of humourless boy and girl groups as indistinguishable as the country’s high-rise apartment complexes, the corporate entities behind K-pop couldn’t have predicted that the chunky, slightly over-the-hill Psy would be the one to break through to global superstardom.

By the same token, the earnest promoters of Seoul wouldn’t have guessed that so much of the world would get its first impression of the city from, essentially, a joke. Before the 21st century, Seoul had no global image to speak of, and only when it suddenly got one did it become clear that nobody quite knew how best to capitalise on it.

‘Seoul is great!’

For decades, Seoul’s own residents had likened their city “to a concrete forest devoid of emotional fulfilment”, Yun writes. “High pollution levels, uncommunicative architectural designs, and the lack of traditional ambience in Seoul were highlighted as major problems.”

Realising that before Seoul could be sold to the world, it first needed to be sold to Seoulites, officials launched poster campaigns emblazoned with friendly faces and voice bubbles saying, “I like to design” and “Seoul is great!”, all meant to assure residents that “in contrast to previous development projects, contemporary urban projects are designed to satisfy individual needs and comforts rather than fulfilling abstract national goals”, according to Yun.

The FF Group, fired up with a characteristically Korean suspicion of political authority (most recently demonstrated in the ejection of the country’s former president) and critical of such a PR push in a city still shot with poverty and neglect, drastically modified this simple messaging. They added stickers to the posters to make those smiling Seoulites say things like: “Children skip meals because [the city government focuses on] design,” and “Only Gangnam is great!”

One has never had to look hard to find a harsh critic of the city, and even its defenders have struggled to articulate what they love about it: I.Seoul.U’s competition included the even emptier expressions “Seoulmate,” “Seouling,” and “Surprising Seoul”.

If Koreans can’t clearly perceive the identity of modern Seoul, the problem must be in large part due to the country’s modernisation process itself, involving an obsessive focus on imitating the west.

In his recent book The New Koreans: the Business, History, and People of South Korea, former journalist and consultant Michael Breen quotes an official who, complaining about his country’s “borrowed” mindset, compares life for a modern Korean to “wearing shirts and pants that don’t fit. Most majors we study were not created by us. Nor are the sports we play, the music we listen to, the movies we watch, or even the food we eat. Most specialists and experts study abroad. In their minds, the ideal destination is not here.”

Physical modernisation has created as many problems as cultural modernisation. Overseen by such uncompromising 20th-century nation builders as dictator Park Chung-hee (who ruled from 1963 to 1979) and Seoul mayor Kim Hyonok (whose Robert Moses-like penchant for building large concrete structures on razed old neighbourhoods earned him the nickname “the Bulldozer”), Seoul swiftly converted from a relatively quiet Japanese colonial city into an industrial powerhouse.

“Criticism of this regime coincided with the decline of manufacturing businesses in Seoul as labour costs increased,” writes Yun. “Manufacturing plants started to relocate elsewhere, mostly overseas, where the cost of labour was much cheaper. As soon as Seoul reached the zenith of its success as an industrial city, as such it was already on the way to its demise.”

The scramble to outfit Seoul for its post-industrial age has seen the government commission many studies; one of the earliest of which, in 2002, found the city’s “urban spaces in general” – the crisscrossing expressways and grey forests of tower blocks – “not conducive to the cultivation of cultures”.

In order to create such spaces, it became more important to generate a “distinctive image of the place, attractive and unique in its own way”, according to Yun. This has put the city, and indeed the country, in “the paradoxical position of having to prove their modernity while preserving Korean traditions” nearly lost in the manic drive to “catch up” with the developed world – and in many cases rediscovering, reintroducing, and even reinventing them. (Some vestiges of old Seoul, such as its traditional hanok courtyard houses, now survive primarily as either tourist attractions or investments.)

This aligns neatly with the conception of Seoul held by Park Won-soon, the city’s mayor since 2011 and an enemy of big projects who, even after taking office, criticised the likes of the DDP as showy and wasteful. He champions free lunches and vegetable gardens in schools, the pedestrianisation of public spaces, and not the demolition, but the reuse of existing structures of all ages – Seoullo 7017’s origin as a 47-year-old eyesore is a showcase example.

Park has made no secret of his higher political ambitions. He may one day leverage his accomplishments in a presidential bid, as did former president Lee Myung-bak, who oversaw the building of the Cheonggyecheon as mayor of Seoul.

Modern Seoul has thus tapped into the fashion for small-scale urban development now seen everywhere from Mexico City to Montreal, from Brooklyn to Berlin. A cornucopia of 21st-century city-dweller’s delights – bakeries, boutiques, independent bookstores, record shops, specialty coffee roasters, urban garden spaces – now appear alongside the traditional humble noodle shops and sprawling markets. And whether they hail from elsewhere in Asia or the west, most of the foreign friends I’ve taken through it express aloud their desire to put down stakes in Seoul, despite acknowledging its lack of conventional beauty.

Seoul has come impressively far – even Seoulites have come to accept their city’s status as a global brand. Magazine B, a Korean publication that scrutinises brands such as Penguin, Netflix, and Muji, recently put out a whole issue devoted to the capital.

If those in charge should learn anything from its checkered branding history, it’s that the way forward lies not in imposing an identity based on existing models – the “soft city”, “design capital” or “global city” – but in first establishing the conditions for the city to find its own, neighbourhood by neighbourhood and even citizen by citizen.

Or perhaps, rather than searching for one, 21st-century Seoul is deep in the process of constructing its identity anew. If Seoul must continue using English-language branding, perhaps it could translate the old Korean-language slogan: “Seoul We Create Together, Seoul We Enjoy Together.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion