When Privatization Means Segregation: Setting the Record Straight on School Vouchers

When Privatization Means Segregation: Setting the Record Straight on School Vouchers

Trump’s Department of Education is proposing to take school vouchers nationwide. But this policy has an ugly segregationist history that “school choice” advocates can’t escape.

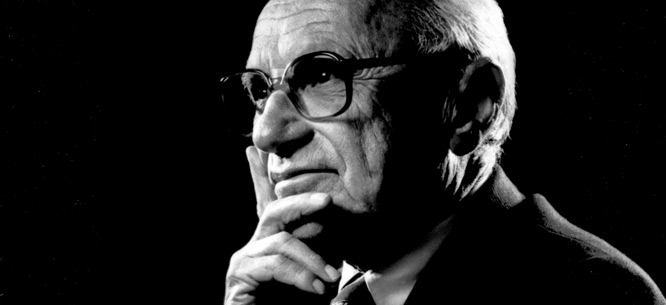

In recent weeks, the issue of private school vouchers has taken center stage in debates over the future of American education. Policy proposals to use public funds for private school tuition vouchers have a long history, dating back to a seminal 1955 essay by Milton Friedman. Over the last twenty-five years, small voucher programs have been established in several states, including Indiana, Florida, Louisiana, Ohio, and Wisconsin, as well as in Washington, D.C.

But the voucher issue took on a new urgency after the election of Donald Trump, given his campaign promise to establish a $20 billion national voucher program. When Trump unveiled his first proposed budget earlier this year, he partnered his program with massive cuts to existing federal education programs, taken largely from funding streams that support the education of students living in poverty. Betsy DeVos, Trump’s secretary of education, is a long-time partisan of vouchers and has been cheerleader in chief for Trump’s education budget cuts and proposed voucher program.

Public education advocates have taken on the Trump-DeVos push for vouchers. The liberal Center for American Progress (CAP) issued two important research briefs, Vouchers Are Not A Viable Solution For Wide Swaths of America and The Racist Origins of Private School Vouchers. In her keynote speech to the American Federation of Teachers’ recent biannual education conference and in her Huffington Post column, American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten addressed the “past and present” of school vouchers, condemning such programs as “only slightly more polite cousins of segregation.”

Both CAP and Weingarten highlighted events around one of the five school desegregation cases that were rolled into the Supreme Court’s historic 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County. With the backing of Virginia’s powerful segregationist senator Harry F. Byrd, the white elite of Prince Edward County defied the Brown decision by closing the entire public school system and diverting public education funds into vouchers to be used at a segregated private academy that only white students could attend. As the battles over the implementation of Brown played out, African-American students were denied access to education for five years in a row. Prince Edward County thus stands as an exemplar of the post-Brown segregationist defiance of school integration and the pivotal role of school vouchers in that effort.

An honest appraisal of the events in Prince Edward County poses a major challenge for voucher advocates. This history is thoroughly documented, both in historian Richard Kluger’s authoritative study of Brown and its aftermath and in two excellent scholarly books on the specific events in Prince Edward County, by Christopher Bonastia and Jill Ogline Titus respectively. There is simply no denying the historical connection between the birth of private school voucher policies and segregationist defiance to Brown. But Prince Edward County is only the beginning of the story.

Milton Friedman, Vouchers, and Racial SegregationIf the push toward private, segregated education was propelled on the ground by local white elites, it found its intellectual underpinnings among leading free-market ideologues. Chief among them was Milton Friedman, whose 1955 essay “The Role of Government in Education” bears close reading. “School choice” proponents universally regard Friedman as the “father” of vouchers, and cite this essay as the movement’s charter. The late Andrew Coulson of the Cato Institute, author of Market Education: The Unknown History, declared that Friedman “launched the modern school-choice movement.” University of Arkansas professor Jay Greene, a fierce advocate of school choice and laissez-faire economics, has described Friedman’s essay as “the seminal work that started the school choice movement.”

Writing a year after the Brown decision, with segregationist defiance in full bloom, Friedman’s essay explicitly addresses the question of vouchers and school segregation in a lengthy footnote. Readers may be aware that the voucher proposal “has recently been suggested in several southern states as a means of evading the Supreme Court ruling against segregation” and conclude that this is a reason to oppose them, Friedman begins. But having reflected on this subject, he has decided otherwise.

Friedman’s argument stakes out three positions that most readers will find on their face incongruent. First, he declares: “I deplore segregation and racial prejudice.” Second, though, he avows his opposition to the “forced nonsegregation” of public schools, by which he means the desegregation of public schools that has just been mandated by Brown. Striking a strange posture of neutrality in the great historic battle to abolish Jim Crow segregation that was opened with Brown, he proclaims that he is also opposed to “forced segregation.” Rather, he seeks a third way: the privatization of public education through vouchers. And finally, Friedman contends that in this system of vouchers, parents should be free to send their children to any private school they choose, including “exclusively white schools.” Once public funds are put in private hands in the form of vouchers, he argues, it would be wrong to prohibit their use in support of racially segregated education.

This last position is precisely the posture that enabled and protected segregationist defiance of Brown in Prince Edward County and throughout the South. Indeed, in his book Capitalism and Freedom, Friedman offers explicit approval of the Virginia law that authorized school vouchers, including those used in Prince Edward County, arguing implausibly that it would have the unintended effect of undermining racial segregation. In fact, the law had precisely the intended effect. For the five years before the Supreme Court ruled that Prince Edward County public schools must be reopened, African-American students were deprived of all education, while white students attended a segregated white academy. After Prince Edward County’s public schools were reopened in 1964, they were underfunded (the county spent twice as much on vouchers as it did on its public schools) and only a handful of white students attended them; the great preponderance of white students used vouchers to attend the segregated Prince Edward Academy. In 1969, the courts finally struck down the Virginia voucher law Friedman supported, ruling that it permitted the continuance of racially segregated education.

Given his actual policy stances on vouchers and segregated schools, one cannot help but wonder how deeply felt Friedman’s professed opposition to segregation and racial prejudice was. But assuming insincerity on his part precludes a full engagement with his thinking. A more fruitful approach is to start by taking Friedman at his word on all three counts, and then examining his attempt to reconcile these different positions. It is in such an analysis of the profound flaws of Friedman’s argument that the full entanglement of libertarian advocacy for vouchers and segregationist opposition to school integration becomes evident.

Are School Vouchers Comparable to Free Speech?In his footnote to the 1955 essay, Friedman’s argument rests on two analogies. To defend his position that vouchers—public funds in private hands—could be used to pay for education in racially segregated schools, Friedman offers an analogy with freedom of speech. The test of support for freedom, he argues, is the extreme case: “willingness to permit free speech to people with whom one agrees is hardly evidence of devotion to the principle of free speech; the relevant test is willingness to permit free speech to people with whom one thoroughly disagrees.” In education, Friedman contends, the extreme case is racially segregated schools: fidelity to freedom demands that those who want a segregated education are free to use publicly funded vouchers to obtain it.

However, there is a significant difference between the freedom to express abhorrent ideas and the freedom to obtain a racially segregated education. No matter how objectionable a particular speech act might be, it does not preclude others from exercising their own freedom of speech. (The sole exception here, shouting another speaker down, proves the rule.) But the “freedom” to obtain a racially segregated education requires, by its very nature, the exclusion of others of different races from that education. In the South, the “freedom” for whites to enjoy a segregated education could not be provided without denying African Americans the freedom to access that same education.

Now, this is hardly a subtle difference, accessible only by refined analysis. All one had to do was observe the actual operation of Jim Crow education to see how it harmed the education of African-American children. Segregationists had openly announced their intention to use vouchers to continue to deny the educational freedom of African Americans, as they did in Prince Edward County. So how could Friedman elide such a basic point in his essay?

Libertarian Freedom and Property RightsThe answer lies in the narrow, constricted concept of freedom Friedman employs. Some context is necessary here. In a classic essay, the political philosopher Isaiah Berlin distinguished between two concepts of freedom, one negative and one positive. Negative freedom is liberty from the government, such as the right to use one’s property as one pleases and the right to speak, publish, and profess one’s beliefs without government restriction. Positive freedom is liberty provided by the government, such as the rights to health care, education, social security and public safety. While negative freedom demands the protection of individual rights, positive freedom requires the promotion of public goods and the general welfare. In democratic societies, citizens enjoy both negative and positive freedom, and government seeks to establish a balance that supports both.

Friedman’s libertarianism lies at one extreme end of the political spectrum, focused on negative freedom to the almost complete exclusion of positive freedom. (Capitalism and Freedom lays out this philosophy in full.) In this view, freedom rests on a foundation of unfettered individual property rights. The public provision of public goods is an illegitimate intrusion upon these property rights, he argues, and coercive of individual freedom. (For libertarians, the exception to this rule is public safety, because they view it as necessary to the protection of property rights.) If a public good is essential, the marketplace will surely deliver it, since, in laissez-faire economic doctrine, it is the “invisible hand” of the market that best realizes the general welfare and the common good.

Vouchers are Friedman’s libertarian political philosophy in action—educational freedom through privatization, replacing the public provision of education with a marketplace. Nevertheless, they depend on public subsidy: Friedman proposes turning over the public funds used for education to individuals, creating an exclusive property right to use those funds in any private school they choose. Precisely because he sees private school vouchers as a property right, he is unwilling to limit how they may be used: their bearers must be free to choose racially segregated schools. In this ideological vision, one turns a blind eye to the damage done to the education of African-American students by segregated schools—damage that vouchers actively perpetuated post-Brown—even when it stares you in the face.

Friedman’s Opposition to Prohibitions of Racial DiscriminationThis stance fits a marked pattern in Friedman’s policy positions, flowing from his extreme libertarian ideology, which extends well beyond private school vouchers. He opposed the prohibition of job discrimination against African-Americans, because the white owners of businesses must be able to exercise their property rights in whatever ways they choose, even if those ways are discriminatory. He opposed the proscription of racial discrimination in housing, because the white owners of rental properties must be able to exercise their property rights in whatever ways they choose, even if those ways are discriminatory. And he opposed the section of the 1964 Civil Rights Act that prohibited discrimination in public accommodations (restaurants, hotels, and places of entertainment), because the white owners of such establishments must be able to exercise their property rights in whatever ways they choose, even if those ways are discriminatory. In each case, he would announce his moral distaste for racial discrimination and segregation, and then oppose measures against them. Property rights always took precedence.

Friedman’s own words on this subject need no embellishment. In Capitalism and Freedom, he declared that legislation chartering the Fair Employment Practices Commission, the forerunner of the federal government’s Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, is the same, in principle, as Hitler’s Nuremberg Laws. This is breathtaking: Friedman is establishing a moral equivalency between Nazi laws that institutionalized anti-Semitism and laid the foundation for the genocide of Germany’s Jews and American laws that redressed racial discrimination in employment, because he finds both to be “coercive” violations of individual property rights—the former by mandating discrimination, the latter by prohibiting it. African Americans have experienced real analogues to the Nuremberg Laws—most notably, enslavement; centuries of brutal violence, rape, and lynching; and Jim Crow de jure segregation—but only the most doctrinaire and myopic of ideologies could find one in legislation designed to overcome a part of that legacy by banning racial discrimination in employment.

The unregulated market in which Friedman places all his trust is an inequality multiplier. This effect is most readily observed in income inequality and concentrations of wealth, but it is no less present around other axes of inequality, notably around race and around gender. After the end of de jure racial segregation and the desegregation of the public sector in areas such as health care and education, the historic exploitation of African Americans persisted in other forms, including discrimination in the marketplace in employment, housing, and public accommodations. Without government regulation of markets, without the enforceable prohibition of discrimination, there are only a few, limited restraints on that exploitation. Moreover, to the extent that one transforms the public provision of public goods, such as education, into unregulated markets—as Friedman proposed to do with school vouchers—one expands the ways in which racial discrimination may be exercised. To address the inequality multiplier effect of the marketplace—including the inequality born of the historic oppression of African Americans—one needs both government regulation of the marketplace and the public provision of public goods. Yet Friedman opposes both on principle. For him, government is almost always the enemy, even when it is providing positive freedoms.

Are Racially Segregated Schools Comparable to Religious Schools?Friedman’s argument for why there should be no barriers to using private school vouchers in racially segregated schools includes a second flawed analogy. How is an array of choices which includes segregated schools different, he asks, from summer camps for children? “Is there any objection to the simultaneous existence of some camps that are wholly Jewish, some wholly non-Jewish, and some mixed?”

This comparison fails on two counts. First, Friedman’s moral equivalence between supporting racial segregation and supporting an affirmative religious or ethnic identity is not only inapt, but offensive. Religious and ethnically identified summer camps and, just as importantly, religiously affiliated schools are organized to provide instruction in a cultural or moral tradition, not to exclude stigmatized and oppressed others. That Friedman would compare the two is not surprising, however, considering that he often portrays racism in a relatively benign fashion, as a matter of poor personal taste.*

Second, religious schools have long been part of the American educational landscape as privately owned, operated, and funded entities, dating back to the era of the founding of free and universal public schools. Their “existence,” to use Friedman’s posing of the question, is not at issue. What is key—and missing from Friedman’s analysis—is the recognition of what is appropriately public and appropriately private in education. American traditions of religious freedom are based on the separation of church and state, with questions of religious identity and affiliation treated as private matters of personal choice. The public funding of religious schools, which Friedman would allow with his private school vouchers, breaches the wall of separation between church and state. It compels the government—and through it, individual taxpayers—to financially support the religious choices of voucher holders. But it is a necessary consequence of collapsing the public into the private, as Friedman would do with school vouchers.

In short, for Friedman, the racial desegregation of public schools mandated by Brown was an “evil,” no less “coercive” than Jim Crow segregation itself. It was on these grounds that he supported the Virginia law authorizing the voucher systems used to maintain racially segregated schools in defiance of Brown and thus deny the educational freedom of African-American students.

When defenders of vouchers declare that Friedman established a tradition of voucher advocacy untainted by efforts to maintain racially segregated schools in the post-Brown South, one can only wonder if they’ve bothered to read the texts that they uphold.

Vouchers, Libertarians, and Southern Defiance to BrownGiven his outsized influence on the “school choice” movement, Milton Friedman merits special attention in any history of school vouchers. But Friedman was hardly alone in defending school segregation on libertarian grounds. Among his peers was James McGill Buchanan, an economist who went on to found the influential school of “public choice” theory. Buchanan was deeply involved in events in Virginia in the wake of Brown.

By 1959, Southern defiance of Brown was beginning to collapse. All of the states surrounding Virginia—Maryland, West Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, and North Carolina—had started to desegregate their public schools. In this context, as Duke University historian Nancy MacLean details in her recent book Democracy in Chains, Buchanan and fellow libertarian G. Warren Nutter penned a proposal to a Virginia state legislative commission that sought to redeem “states’ rights” defiance of Brown by privatizing its public schools using vouchers. The Buchanan-Nutter proposal was written and circulated with Friedman’s support, and mimicked the language and argument of his 1955 essay. Like Friedman, they declared their opposition to both “involuntary integration” that complied with the mandate of Brown and “involuntary (or coercive) segregation,” and proposed private school vouchers as a third way. Taking issue with moderate white Virginians who argued that the state could not afford to subsidize an education system of private segregated schools and should comply with Brown, Buchanan and Nutter proposed that the state sell off its entire stock of public school facilities to finance their experiment in privatized education.

It was too extreme a proposal for even the segregationist Virginia state legislature to swallow. That legislature would not object when Prince Edward County closed its public schools and provided white students with vouchers for a segregated school, and it would pass legislation allowing local districts across the state to establish vouchers systems that could be used in segregated white academies. But by a narrow majority, it stopped short of forcing the Prince Edward County model on the rest of Virginia by eliminating the state constitution’s guarantee of free public schooling and mandating private school vouchers for all—likely out of consideration for the political risks involved. Buchanan blamed PTAs, teacher organizations, and school-of-education faculty for this defeat.

Soon, though, the privatization agenda achieved a national platform when Friedman, Buchanan, and Nutter became advisors to the 1964 Republican Party presidential campaign of Barry Goldwater. Like them, Goldwater invoked “states’ rights” to oppose the Brown decision and “coercive” racial desegregation. For Goldwater, the prohibitions on racial discrimination in public accommodations and employment in the 1964 Civil Rights Act were “hallmarks of the police state and landmarks in the destruction of a free society.” Goldwater would go down in a crushing defeat, capturing only his home state of Arizona and five states of the Deep South—even Virginia went for Lyndon Johnson. But his campaign formed the nucleus of a zealous libertarian politics that would go on to capture the Republican Party and put private school vouchers on its agenda.

Voucher Partisans on the DefenseIn the wake of the CAP reports and Randi Weingarten’s speech, voucher advocates were compelled to respond. Three lines of defense have emerged to dismiss the historic connection between private school vouchers and racial segregation. They are as unconvincing as the original arguments.

First, there is the remarkable contention that the origins and history of private school vouchers is simply irrelevant. Take this op-ed, extraordinary in that it was penned by an academic who professes to be an education historian. The headline sums up its line of argument: “early proponents [of vouchers] had racist motivations. So?”

But history is quite relevant to contemporary debates. When Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos refused to pledge that a Trump administration voucher program would prohibit the use of vouchers in schools that discriminated, was she not repeating the position of Milton Friedman, stripped of its scholarly trappings? In a Trump administration that has systematically rolled back the Education Department’s civil rights work, what reason is there to believe that their unregulated private school vouchers would function in a way that respected the civil rights of students?

Second, there was the “best defense is an offense” approach, captured in a post at pro-market education news site The 74. According to this view, Weingarten and the AFT are “projecting” their own failures to support racial integration in schools when they criticize the racist origins of school vouchers. Insofar as there is any substance offered for this accusation, it is in the claim that the New York City teachers’ strikes of 1967 and 1968 were “a notorious fight against integration.”

The post is a spectacular display of historical ignorance. First, the AFT has a proud history of opposing racial segregation and supporting the integration of public schools. It was the only national education organization to file an amicus brief in support of the Brown plaintiffs, and it was the very first national union to expel locals who would not integrate, at a real cost in membership and income. When Prince Edward County adopted vouchers and closed its public schools, it was the AFT, together with the African-American Virginia Teachers Association, that helped organize the county’s freedom schools; the AFT brought teachers from its New York City and Philadelphia locals to Virginia to teach the African-American students who were being denied an education. These schools were an early prototype for the better known freedom schools of Mississippi Freedom Summer. Indeed, many of the same AFT teachers who had gone to Prince Edward County in 1963 planned and then taught in the Mississippi freedom schools during the summer of 1964, when fellow Freedom Summer civil rights workers Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner were tortured and brutally murdered by the Klan.

Second, in the 1967 and 1968 strikes, it was the AFT local, New York City’s United Federation of Teachers, that took the side of racial integration. In this stance, they had the support of A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and, until his assassination in April 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. The other side of this conflict was led by revolutionary black nationalists and Black Power radicals who opposed integration. (The claims of the 74 post were such a garbled version of the real history that in its first version, since corrected, it had the Ocean Hill-Brownsville strikes located in a non-existent Crown Point section of Brooklyn.) Perhaps most disappointing is that this stunningly ignorant piece was written by a former assistant secretary of communications at the U.S. Department of Education.

The most measured defense of vouchers came from those who conceded the “problematic” use of vouchers in the defiance to Brown, but sought to present it as a minor chapter in the history of vouchers. A particularly imaginative version of this tack, which reaches back into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to unearth “voucher” advocates in eras before free and universal systems of public schooling were even established, was elaborated in the National Review by American Enterprise Institute scholar Frederick M. Hess. This approach neglects the scholarship on the events in Prince Edward County, choosing to treat those events as an almost inexplicable outlier, when in fact they were a last gasp of the mass segregationist defiance of Brown that had erupted across the South. In a little more than a decade, over 600 delegations from across the South came to visit and observe the county’s segregated Prince Edward Academy, in the hope that it would provide a model for similar schools in their home districts.

In some cases, imagination in voucher proponents fades into perverse fiction. In an echo of Betsy DeVos’s widely lambasted claim about historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), another advocate claims freedom schools, born in response to the use of school vouchers to deny the students of Prince Edward County an education, as part of an African-American tradition of “school choice.”

Try as privatization advocates might, there is no getting around the segregationist history of school vouchers in the United States. From Milton Friedman to the recalcitrant white elites of Prince Edward County and the legislators they voted in, the forerunners of today’s “school choice” movement understood their freedom as the freedom to deny others an equal education. That history continues into the present: empirical studies of vouchers programs in the United States and internationally show that they increase segregation in schools. As a Trump administration that openly appeals to white racial resentment proposes a massive school voucher program, we would be foolish to ignore the policy’s origins.

Leo Casey is executive director of the Albert Shanker Institute, a think tank and policy advocacy arm of the American Federation of Teachers. He worked for twenty-seven years in New York City public schools, where he served as a Vice President of the city’s United Federation of Teachers.

* See, for example, this passage in Capitalism and Freedom, where Friedman is discussing racist job discrimination: “Is there any difference in principle between the taste that leads a householder to prefer an attractive servant to an ugly one and the taste that leads another to prefer a Negro to a white or a white to a Negro, except that we sympathize and agree with the one taste and may not agree with the other?”