A satellite image of Hurricane Harvey on August 25. Photo by NASA via Getty

As I write this on Wednesday morning, the flood waters after Hurricane Harvey have finally begun to recede. In addition to answering questions about whether this storm brought more death and destruction to Houston than Katrina brought to New Orleans in 2005, we can now fully take stock of the storm from a meteorological standpoint. One incredible stat: The preliminary rainfall total taken by one Houston-area rain gauge clocked the most rain for one event in the US, ever.This was one hell of a storm.So now it's time to argue about climate change! Right-wing writers like Michael Bastatch at the Daily Caller have been clicking their tongues at liberals like former Barack Obama adviser Ben Rhodes for daring to politicize the hurricane by suggesting on Twitter that Republicans who refuse to acknowledge climate change will have to answer for storm-related death and destruction in the future."Democrats have often linked individual extreme weather events to manmade global warming, despite warnings from scientists that doing so is problematic," Bastatch writes, correctly. When it comes to Harvey, or the disastrous ongoing floods in India, Bangladesh, and Nepal that have killed more than 1,000 people, Bastatch is right. You can't blame a storm on climate change any more than you can blame an individual crime on a crime wave. But while technically correct, that sort of argument is incredibly disingenuous.So how should we talk about man-made climate change when it comes to extreme weather events? I'm glad you asked. Here's how:Yes, extreme weather is increasing

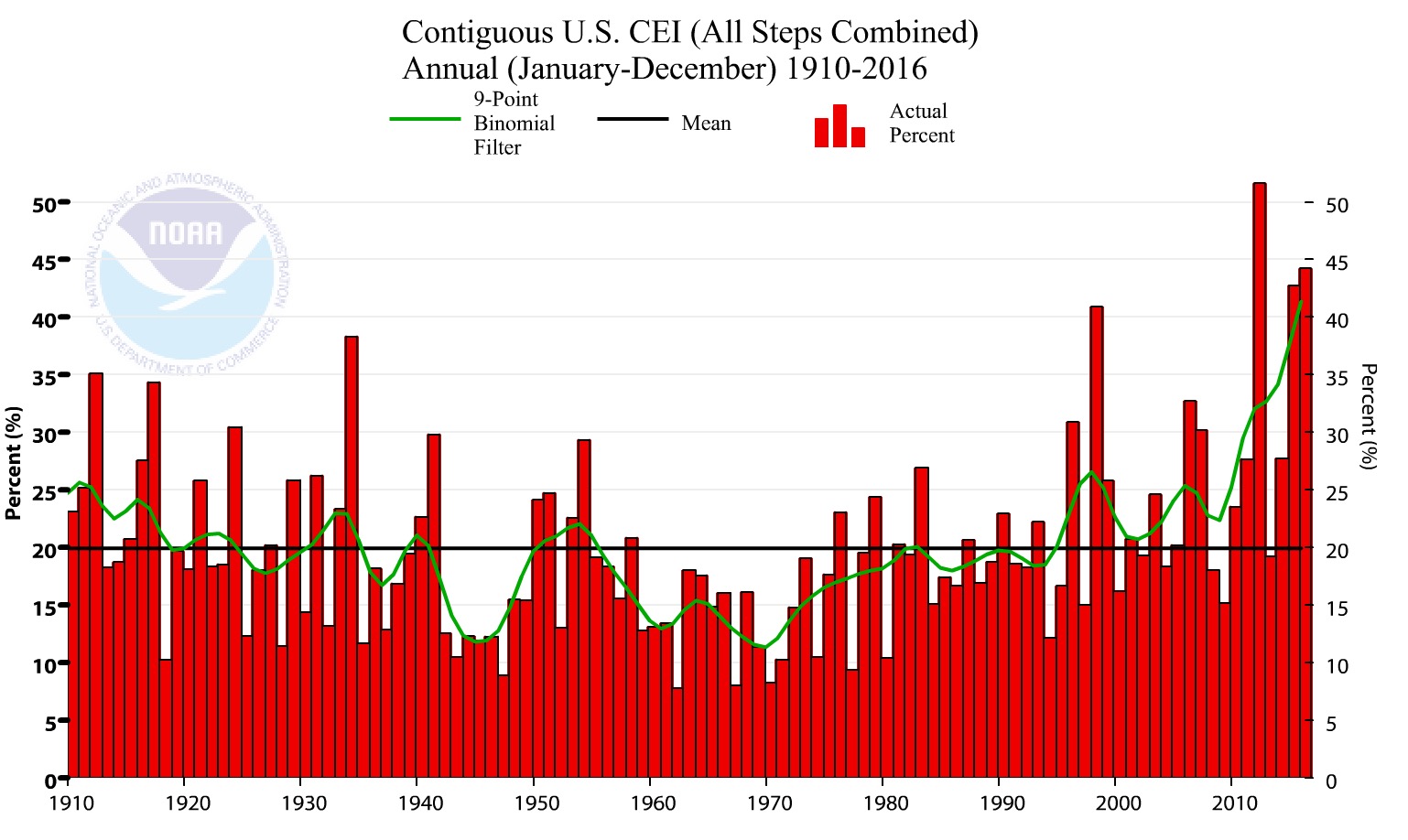

The "U.S. Climate Extremes Index," year by year. Graph via NOAAFirst of all, are we (Earthlings) really trending toward more and larger storms? It's an understandable question, because climate change deniers keep harping on the fact that Harvey was the first Category 4 hurricane to make landfall since Charley in 2004.The short answer is "Yes." But there's a long answer, and it's "More? Probably not in the case of hurricanes. Larger? Almost certainly."With regard to rainstorms, "the best evidence is from changes in extreme rainfall, [with] very clear increases, strongest in Northeast," according to Kevin Trenberth, climate analyst at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), an organization devoted to answering this exact question, and others like it. But Trenberth cautioned that for many reasons—technological limitations mainly—in the case of hurricanes, "the evidence is equivocal."So as a general rule, climate change will bring more extreme rainfall, but don't expect more hurricanes. "With higher sea [temperatures], we expect numbers to go down," Trenberth told me. But that's not necessarily good news: "We expect higher intensity and size, and longer lifetimes in general, but fewer storms, because one big storm can replace three or four smaller storms."Briefly, warmer air and water allow more ocean water to evaporate. Boiling is one extreme example of this sped-up evaporation, but at most of Earth's surface temperatures, some water always wants to turn into vapor. Anywhere it's warmer, "you've got more molecules moving faster, and more of them are going to be able to jump up out of the water and become vapor," according to Jeff Masters, one of the co-founders of Weather Underground (the weather service, not the eponymous leftist militia).In the case of Hurricane Harvey, which formed over (and in) the Gulf of Mexico, the water was "about a degree centigrade warmer than average, at least compared to what they would have been 40 years ago," Masters said. (Other climate scientists offer slightly lower estimates, but the point remains.) That increase in temperature, he said, corresponds to 7 percent more moisture evaporation. "So we can assume in Harvey's case that about 7 percent of the rain that fell was due to global warming," he told me.Evaporation's role in global climate change works in ways that are "not yet clearly understood," according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Consequently, Masters told me he'd seen alternative models that said evaporation may have led to as much as 30 percent more rain during Harvey. But the one degree centigrade–7 percent more precipitation figure has a history of reliability, so let's go with that for now.That also gives us a sense of how much worse hurricanes will be in the future. "If the oceans go another degree centigrade warmer, say 20 years from now, you're going to add another 7 percent on. Seven percent plus 7 percent is 14 percent," Masters told me.A word of caution: Texas A&M University meteorologist John W. Nielsen-Gammon, who is also the official climatologist of Texas (a state whose elected officials generally refuse to talk about climate change at all), told me that many other factors can change rainfall rates, including the rate of [vapor's] ascent, the humidity of surrounding air, and the intensity of disturbances that might cause that ascent in the first place." So, he told me, "the warmer-equals-wetter rule, [exclusively] applies to extreme rainfall—when all conditions are right—and only on a large-scale average basis." In other words, just to be on the safe side, let's only bust out this formula during hurricanes."Sea level rise has nothing to do with hurricanes, except that it makes the starting level for any storm surge that much higher," Nielsen-Gammon told me. In other words, it has plenty to do with hurricanes—just nothing to do with the amount of wind or rain. Storm surge is what you get from a hurricane as the wind pushes sea water inland, causing coastal flooding. In the case of Harvey, overfull rivers in the Houston surged toward the coast at the same time, resulting in more floodwater that piled up where two surges met.The changing climate likely made all this worse: As Nielsen-Gammon pointed out, the water started out that much higher before the surge. On average, the global sea level has risen about 2.6 inches since 1993 as of 2014, and perhaps 8.3 inches since 1880. But that's an average. Thanks to coastal erosion "along the central Texas coast, the sea level rise has been about a foot and half," Jeff Masters of the Weather Underground told me."This higher sea level means that storm surge [is] higher and reaches farther inland. So, given the exact same hurricane strength, the storm surge will go farther inland now than it did 50 years ago," said Sean Sublette, meteorologist with the Climate Matters program at the nonprofit news organization Climate Central. Nonetheless, calculating the precise connection between sea level rise and storm surge involves some very tricky number-crunching, since there's no uniformity to the location and intensity of these surges. Precise claims about this effect, then, are pretty much impossible.

The important thing is that this is going to happen again and again. Climate change is a slow steady rewriting of the rules that govern weather, bit by bit. So while we don't know how to gauge its effects on storms, the global cost of natural disasters appears to be on the rise—including the monetary cost. David Roberts of Vox pointed out that now that we know we're in for more catastrophes in the long-term, even though reducing emissions is still critical, guilt-tripping people for generating greenhouse gases is a silly way to protect American communities from flood damage.But it seems that some of the same people who have been denying climate change for years are also not interested in mitigating the damage. Donald Trump's executive order earlier this month, rolling back Obama-era provisions aimed at avoiding infrastructure damage from future climate-related calamities, was downright perverse. If the order is implemented successfully, Americans in future decades will be the ones who suffer materially from Harveys and Katrinas still to come. And there will definitely be more storms like this.Follow Mike Pearl on Twitter.

Advertisement

Yes, extreme weather is increasing

Advertisement

A hotter Earth is to blame

Advertisement

Sea level rise also plays a role

Advertisement

The important thing is that this is going to happen again and again. Climate change is a slow steady rewriting of the rules that govern weather, bit by bit. So while we don't know how to gauge its effects on storms, the global cost of natural disasters appears to be on the rise—including the monetary cost. David Roberts of Vox pointed out that now that we know we're in for more catastrophes in the long-term, even though reducing emissions is still critical, guilt-tripping people for generating greenhouse gases is a silly way to protect American communities from flood damage.But it seems that some of the same people who have been denying climate change for years are also not interested in mitigating the damage. Donald Trump's executive order earlier this month, rolling back Obama-era provisions aimed at avoiding infrastructure damage from future climate-related calamities, was downright perverse. If the order is implemented successfully, Americans in future decades will be the ones who suffer materially from Harveys and Katrinas still to come. And there will definitely be more storms like this.Follow Mike Pearl on Twitter.