Mark Healey Is the Greatest Athlete You’ve Never Heard Of

He surfs sixty-foot waves, performs Hollywood stunts, and can hold his breath underwater for six—six!—minutes. Now he's freediving to tag hammerhead sharks for science.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

The island of Mikomoto is a barren, windswept, wave-battered chunk of basalt infested with sharks and scoured by current, and looks as if it erupted from the fever dream of a malarial sea captain. Six miles offshore of Japan’s quiet port town of Minami-Izu, its waters are so treacherous that the 25-acre uninhabited island was chosen in 1870 as the site of one of the country’s first stone lighthouses, a 75-foot tower wrapped with black stripes. For Mark Healey, these are all the ingredients of a good time.

“This should be fun,” he says as the Otomaru, our 40-foot chartered fishing boat, pulls into a rocky cove.

Clad head to toe in a three-millimeter camouflage wetsuit with fins to match, he looks like he just swam out of a Special Forces unit. He has a black GoPro camera (one of his many sponsors) strapped to his head; it’s an accessory so common in his daily life that it may as well be a permanent appendage. A knife is cinched at the hip to his weight belt, along with a trio of two-pound lead weights, custom-made to reduce drag in the water. A black glove protects his left hand. In his naked right he holds a four-foot teakwood Riffe speargun.

Healey takes a giant stride off the Otomaru into the 80-degree water. After a few minutes of deliberate breathing, he bends at the waist and dives. His fins—three and a half feet long for freediving—break the water with a gentle splash, then slide beneath the surface. One, two, seven long, smooth kicks take him down to 30 feet, at which point the lead weights take over, pulling him deeper. One minute in—a point when even strong divers would head up—Healey scans the depths and glides down to 80 feet.

A 34-year-old professional big-wave surfer, Healey has built a career chasing down the dangerous and nearly impossible. He’s a perennial finalist in the World Surf League’s Big Wave Awards—the discipline’s equivalent of the Oscars—having won the top prize in the Biggest Tube category in 2009 for a barrel in Oregon and the Biggest Paddle-In Wave in 2014 for a 60-foot monster at Jaws, on Maui’s north shore. He once won the Surfer magazine poll for Worst Wipeout, crashing on a punishing wave at Teahupoo, in Tahiti, that would have vaporized most surfers. But Healey isn’t in Japan to ride waves—he’s here to swim with sharks.

As a member of a six-person scientific expedition, he has come to Japan for two weeks to tag an endangered population of scalloped hammerheads that congregate around Mikomoto. The sharks have plummeted in numbers by as much as 90 percent, largely due to overfishing and an insatiable appetite in Asia for fin soup. The scientists hope that the data they record, such as population sizes and migratory patterns, will improve conservation policies regionally and globally.

Between Austin Gallagher, the 30-year-old marine ecologist and founder of the conservation nonprofit Beneath the Waves who assembled the group, and the other scientists, there are enough degrees on board to rival a thermometer. Yet Healey, a man whose traditional schooling ended after the seventh grade, is the linchpin of the project. He’s a champion spearfisherman and freediver who can hold his breath for an astounding six minutes underwater, and the scientists can’t tag these notoriously hypersensitive sharks without him.

“Hammerheads are nearly impossible to catch on a line without killing them,” Gallagher says. “They need to be tagged on their turf, underwater. Because they’re so skittish, they stay away from the noise and bubbles created by scuba divers.”

Battling a heavy swell and strong currents, Healey will dive as deep as 135 feet, sneak into a school of up to 100 sharks, shoot a few with satellite or acoustic radio tags in the noninvasive area behind the dorsal fin, and then swim back to the surface—all on a single breath of air.

The hammerheads the team is after, which can grow to eight feet and 200 pounds, are small fry compared with the beasts Healey has previously pursued. In 2011, he traveled to Mexico’s Guadalupe Island to dive with great white sharks for a National Geographic television shoot. On the first day, after 30 minutes watching a trio of the one-ton animals arc through the water, Healey swam away from the safety of the boat and joined them. The biggest shark in the group interrupted its meander and made toward Healey like a guided missile. Is this a bad idea? he wondered, all the while holding his ground. As the shark swam beneath him, Healey extended his arm in a terrifying handshake and grabbed its dorsal fin.

The shark didn’t flinch any more than if Healey had been a remora. He wasn’t prey—he’d become an object for the sharks to use in competition for dominance. When he was paired off with one shark, the others stayed away. When a shark began to dive, Healey would let go. “The last place you want to be is kicking 70 feet back up through the water column. That’s when they eat you,” he told me.

During one ride, Healey was piggybacking on a shark as it approached a floating tuna head. He could feel the beast begin to open its giant mouth. Alarmed at what a feeding great white might do if it felt his full weight when it broke the surface, he slid off.

But after hours in the water in Japan, Healey hasn’t yet seen a shark. “It’s a numbers game,” he says during a post-dive recovery float. “The more time I’m underwater, the more likely we are to find hammerheads.” He takes a few more long breaths and disappears beneath the surface.

Watch: Mark Healey Tags a Shark

Scalloped hammerheads are famous for congregating in huge schools around seamounts. Thought to be attracted to the magnetism of volcanic islands like Cocos and the Galápagos, in the eastern Pacific, and Mikomoto, they may use underwater rock formations as resting and social centers during the day and as points of reference for nocturnal hunting. Their distinctive heads could help them detect the electromagnetic signals of the earth and other animals.

The scientists aboard the Otomaru want to understand the very basics of these hammerheads. Why do they come to Mikomoto, what are they doing here, how long do they stay, and where do they go next? By identifying their habits and highways, the scientists can maximize conservation efforts.

Gallagher has put together an international group for the expedition. David Jacoby, a postdoctorate at the Zoological Society of London, studies shark social networks and once bred 1,000 cat sharks in captivity. Yannis Papastamatiou, also from the UK, is a jujitsu black belt who specializes in using underwater acoustics to study shark movement as an assistant professor at Florida International University. Yuuki Watanabe, an associate professor at Japan’s National Institute of Polar Research, is our local lead. Tre’ Packard, executive director of a Hawaii-based art and conservation nonprofit called the PangeaSeed Foundation, suggested the expedition to Gallagher in the first place, having dived at Mikomoto before with one of only a handful of commercial operators that run trips here.

Our plan makes the long, hot August days on a small fishing boat almost civilized. At night we stay at a traditional Japanese guesthouse in Minami-Izu, eating delicious local fare as we sit on tatami-mat floors. Each morning we board the Otomaru by 8 a.m. and hit the water 30 minutes later. As an experienced freediver myself, I often follow Healey down but have no illusions of keeping pace.

Battling a heavy swell and strong currents, Healey will dive as deep as 135 feet, sneak into a school of up to 100 sharks, shoot a few of them with satellite or acoustic radio tags, and then swim back to the surface—all on a single breath of air.

Healey’s been on a previous research expedition, in 2014 in the Philippines, where he tagged nine thresher sharks. On this trip, he’ll use two kinds of tags. Satellite tags will record the sharks’ seasonal migration, then pop off after six to twelve months, sending GPS data of the animal’s path from the surface. Smaller acoustic tags will stay on for up to a year and transmit local data when the shark comes within a few hundred feet of an underwater receiver, which the scientists will moor to the seafloor. The team plans to return annually to swap out the receivers, collect a year’s worth of acoustic data, and tag more sharks.

Studying these animals is not simply an academic exercise. Healthy hammerhead populations help maintain healthy oceans and economies. A 2007 study in the journal Science correlated a more than 90 percent decline in hammerheads and other sharks along the eastern seaboard of the U.S. with an explosion in the population of their prey, cow-nosed rays. The rays then consumed enough bay scallops to collapse North Carolina’s century-old fishery. “People get so riled up about sharks for the same reasons they get riled up about politics and religion,” Healey says. “It’s all about power and control.”

Which we don’t seem to have a lot of thus far. Though we’ve been casting Healey over the side each day like a fishing lure, we still haven’t seen any hammerheads. To make matters more difficult, two Category 4 typhoons are spinning our way, threatening to cut our trip a week short, and the conditions at Mikomoto are deteriorating, bringing wind, rain, and seasickness. On the bow, one of the scientists heaves into the pitching waves, a fluorescent yellow blend of miso soup and stomach bile. Healey, astern and at ease, pulls out a tin of chewing tobacco, packs a dip, and awaits marching orders.

The four-person Japanese crew of the Otomaru—a captain, two sailors, and a divemaster—are eager to return to harbor as the boat gets nailed from all sides by the growing swell. But the team needs a win and decides on setting a receiver.

Gallagher, Jacoby, and Papastamatiou clamber into scuba gear. They plan to set the receiver a few hundred yards from shore. Once it’s secured, they’ll fire a float to the surface, where the boat can take a GPS reading to mark it. The captain, however, doesn’t want to risk bringing the boat that close to the island. “I’ll do it,” says Healey, volunteering to swim to the float with his handheld GPS. “Back into wardrobe.”

The float pops up 20 minutes later, and Healey swims a quick 400 yards out and back. Wind and rain lash the deck and our faces; the black ocean is colored with whitecaps. Gallagher, Jacoby, and Papastamatiou surface and are swept toward a jagged house-size rock shaped, appropriately, like a shark fin. Inching toward them, the Otomaru gets pounded by waves.

“This is bad,” Papastamatiou says in the water.

Gallagher looks concerned. “Are we going to be OK?” he asks.

A deckhand throws a rope to the divers as the captain slams the boat in reverse to avoid hitting the rock. The Otomaru pitches like a rocking chair. One moment the gunwale is ten feet in the air, the next it’s slamming into the water. Healey helps haul the divers in one by one, a tumble of fins, tanks, and regulators.

“That was an education,” Papastamatiou says. The scientists are shell-shocked, and the crew is angry. The captain cranks the throttle to head back to shore. Healey throws his arms toward the heavens triumphantly, a grin stretching from here to the mainland.

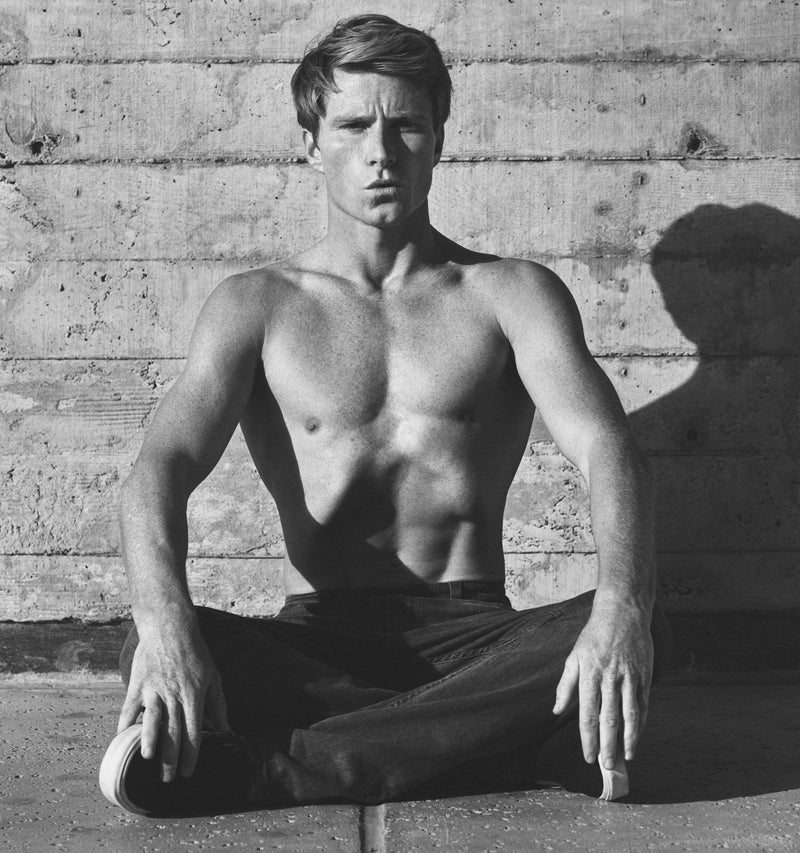

Standing just five foot nine and 153 pounds, with ginger freckles, narrow-set eyes, and a chiseled jaw, Healey looks like a blend of Richie Cunningham and Aquaman. Though new to field biology, he’s been turning heads in the surf world for two decades. At the age of 14, he made a splash riding 30-foot waves at Waimea Bay. He cashed his first paycheck as a professional three years later and has been a fixture in the world’s scariest lineups ever since.

“As a waterman, Mark is unrivaled,” says big-wave icon Laird Hamilton. “When it comes to riding giant waves, diving deep, and hunting fish, he’s the total package—unique even among us.”

A knack for doing the right thing in the wrong place has landed Healey stuntman gigs on Chasing Mavericks and the reboots of Hawaii 5-0 and Point Break. About a year after walking away from his longtime sponsor Quiksilver, he helped launch the surf-apparel company Depactus in February 2015 as a minority partner and the face of the brand. But despite his success on a surfboard, it’s not his first love. “People always think of Mark as a professional surfer,” says spearfishing record holder Cameron Kirkconnell, “but the truth is, he surfs to support his diving habit.”

Healey learned to swim before he could walk and estimates that he’s spent “a third of the year with a dive mask on since the age of 12.” He was born and raised and still resides in Haleiwa, on Oahu’s North Shore. His father, Andy, is an avid waterman who would wrap his tiny toddler in a life vest, give him a mask and snorkel, and pull him through the water clinging to a fishing buoy. “He took to it immediately,” Andy recalls.

Fishing was a way of life in the Healey household, a passion born from a love of the ocean and the need to eat. On calm evenings, they would paddle a half-mile out to a lonely rock in the Pacific and cast lines until sunrise. “There always had to be some element of misery to it,” Healey remembers fondly.

Money was tight. Andy was a carpenter who pounded nails for a living and a boxing bag for fun. Healey’s mother, Bitsy, cleaned houses so she could keep an eye on him while she worked. “It was hard to find a babysitter who could keep up with him,” she says. They shared a three-bedroom house with termites and holes in the floor. Bitsy would cover the latter with throw rugs, which Mark turned into traps, baiting friends into a chase and laughing as they fell into the mud below. Mark and his brother, Mikey, bounced between public and private school until Bitsy began homeschooling them in 1994.

Pale, blond, freckled, and undersize, Healey suffered a phenotype cursed in his poor, rural neighborhood. He didn’t crack 100 pounds until long after he’d gotten his driver’s license. Bloody noses and black eyes weren’t uncommon. He would never be able to fight all the bullies, despite boxing training from his father and martial-arts classes. “If you didn’t confront a situation, it would fester for years,” Healey recalls. “The only way to get any respect was to do things in the ocean that other people couldn’t.”

North Shore lifeguard Dave Wassel heard stories of this bobble-headed young gun who was riding giants. One day, while surfing at Pipeline, he noticed Healey “just owning it” in surf two stories tall, breaking in water two feet deep. In the parking lot afterward, Healey did something else Wassel had never seen. He pulled out a stack of phone books and put them on the driver’s seat. “He couldn’t see over the steering wheel!” Wassel says. “The kid was 17 years old, charging the heaviest waves in the world, and he needed a booster seat to drive home!”

By day five, we are in desperate need of some of that Healey magic. Photographer Kanoa Zimmerman and I float on the surface, watching Healey dive. Four stories down, he swings into a hover, scanning the murk for shadows. A stiff current nudges him off-axis, but he levels himself with a twitch of the left fin. His movements are balletic, part of a subtle dance in which the slightest shifts are made with the greatest intention. “Most people have the ability to be calm sometimes,” Laird Hamilton told me, “but Mark’s calm all the time. That’s very useful in high-risk situations, whether riding giant waves or diving with sharks.”

From below, a shadow appears. Two more arrive, then five, then dozens. Healey stirred up a school of Galapagos sharks loitering in a cloud of fish spawn.

Six feet long and too curious for my taste, they approach from all directions, darting within inches of me, probing for weakness like a pack of street punks in a dark alley. One of the biggest sharks has a distinctive wrinkle on its tail fin and approaches with its gills puffing and dorsal fins down, a display of aggression. All I see is toothy biomass, but Healey’s reading the fine print. “The dominant ones are usually highest in the water column,” he explains later. “They’re the ones that will test you. If you can trick them into thinking you’re the boss, the rest generally fall in line.”

The key word is trick; Healey’s well aware of what even sharks like these can do to a femoral artery. Still, he doesn’t pass up the opportunity for play. Seeing that one of the sharks has a fishhook and line in its mouth, he takes the opportunity for a little benevolent dentistry, swimming down and yanking it out.

On the boat, preparing for another round of diving, I ask Gallagher if it makes sense to start tagging the Galapagos sharks. Water temperatures are hovering around the low eighties, which makes for easier diving but a challenging hammerhead hunt. When the ocean is this warm, the sharks stay deep to stay cool. The boat has a fish finder, but it doesn’t do much good tracking the fast-moving schools. Gallagher’s assurance at the beginning of the trip that we were heading to Mikomoto during a “miracle season,” when schools of 100 hammerheads are common, was starting to feel more like a taunt than encouragement. But the recent Galapagos sighting fuels optimism. “Save the tags for the hammers,” he says.

The crew of the Otomaru don’t share Gallagher’s enthusiasm. “Storm coming,” says the captain, swinging the boat back toward the mainland.

We’ve been in Japan nearly a week and haven’t tagged a single hammerhead, and the conditions will likely continue to worsen because of the impending typhoons. “There’s a very good chance that if we don’t get a tag on a shark in the next 48 hours,” Healey says, “this whole thing is a bust.”

At the guesthouse after dinner, Jacoby and Papastamatiou sit on the floor preparing mooring lines for more receivers. The materials should last years, Jacoby explains, “but that depends on the waves.”

“Forty feet deep should be fine,” Healey says. “The biggest wave I’ve ever seen broke in 60 feet of water.”

“Where was that?” I ask.

Healey, who’s constantly tracking storms and taking last-minute flights in search of the world’s biggest swells, pauses, weighing how much of this hard-won information to share. “Africa,” he replies.

I press. “Is that your cagey way of saying, ‘I’m not going to tell you, because that’s where I might find a 100-foot wave’?” He considers a reply, then thinks better of it, shaking his head as he walks away.

Healey knows each giant ride is a life or death proposition, and he’s seen the high cost of this obsession. In December 2005, pro surfer Malik Joyeux took an awkward wipeout at Pipeline and didn’t surface. Healey ran into the water, swimming laps through the lineup until he finally helped pull Joyeux’s body off the reef. “His brother watched the whole thing,” Healey recalls. “I’d run back up the beach, and when I passed him, I could see his expression changing from confusion to shock. I was probably the last person to shake Malik’s hand.” Five years later, after Hawaiian surfer Sion Milosky drowned at Maverick’s, Healey accompanied his widow to California to retrieve his friend’s body.

“There are a lot of things working against people in this sport,” Healey says. “It's becoming apparent that those odds are coming up around me. Once you've seen one of your friends die, can you keep going? Do you still want to do it?”

“There are a lot of things working against people in this sport” Healey says. “It’s becoming apparent that those odds are coming up around me. I take my preparation very seriously, but there are so many factors to longevity besides the odds of surviving something bad. There’s the mental aspect. Once you’ve seen one of your friends die, can you keep going? Once you’ve helped their families and have seen the grief it causes, do you still want to do it? You have to be born with a certain personality type to keep coming back. But it will never be safe. And the day that it is, I won’t want to do it anymore.”

Healey trains by surfing and diving most days, doing a variety of workouts on the beach and in the pool, and hiking and bow hunting in the mountains. He recently started doing a program a few times a week called Ginástica Natural, a hybrid of yoga and jujitsu focusing on movement and breath. Still, he’s no stranger to carnage, having split his kneecap in half, broken his heel, and ruptured his right eardrum four times, which left him disoriented underwater, nearly causing him to drown. Despite the dangers, he calls life as a professional surfer “the greatest scam on earth.” But he knows the ride won’t last. Now in his thirties, he has entered the decade that most pros call retirement. “The surf industry will bro you into bankruptcy,” he says. “I would rather light myself on fire than go begging for pennies as a grown man.” Instead of doubling down on contests and sponsorships, Healey is venturing into waters most surfers don’t: building businesses.

In addition to Depactus, in 2014 he launched Healey Water Ops (HWO), an operation that gives high-paying and high-profile clients the chance to explore the ocean like, well, Mark Healey. Two-week guided experiences start at $100,000 and have Healey teaching clients how to swim with sharks, surf waves far beyond their comfort zone, spear giant tuna, or partake of any other saltwater adventure conceivable. From tech moguls to Arab royalty, his client roster is a Fortune 500 list of ocean enthusiasts. (Thanks to HWO’s nondisclosure agreement, Healey is as tight-lipped with names as he is about surf breaks.)

Volunteering for expeditions is also part of his expanded career plan. Remote seas are expensive to explore, and trips like this are a way to scout locations for other adventures and deploy his skills for a commendable purpose. “I love having the opportunity to incorporate old knowledge like spearfishing into modern conservation and scientific discovery,” he says.

The sky brightened the next morning. “Mark, it would be great if we could get some data on their behavior and get close to these animals,” says Jacoby, the expert on shark social networks. Healey taps the GoPro on his forehead in affirmation.

We plunge into the ocean, which is still and blue, with 50-foot visibility and little current. The bathymetry is spectacular, a jigsaw of basalt domes, craggy ridgelines, and wide channels. The water explodes with life—there’s so much to see that it’s hard to focus. Thick schools of seven-inch-long fusiliers, blue with sunburst yellow racing stripes down their backs, swim in tight formation appropriate to their military namesake. Two pilot fish, the size of thumbnails and dressed in the black and white stripes of a convict, choose me as their escort.

Suddenly, a cry comes from the Otomaru. “Mark!” Gallagher yells. The unmistakable falcate dorsal fin of a hammerhead cuts the surface, but it’s a football field upcurrent from Healey. He’s got no chance.

Healey climbs back aboard. Gallagher and Papastamatiou, staring down a shutout, finally tell him to start targeting Galapagos sharks, too. “It’s valid data,” Papastamatiou says with a hint of desperation. “No one’s ever done that out here.”

We motor toward the fin sighting, but the shark is long gone. We drop Healey into the water at the mouth of the cove where we moored the receiver a few days ago. Fifteen minutes later, he’s swimming back to the boat. “Got a hammer,” he says quietly. The boat erupts in cheer.

While the scientists slap backs and high-five, Healey sits alone on a far edge of the gunwale. He’s all business now, hunched over, elbows on his knees, hands cradling his chin. He doesn’t even bother to take off his mask between dives. Usually verbose, he replies curtly when asked what he’s seen down there: “Sharks and darkness.”

We head to the east side of the island. Zimmerman, Healey, and I jump in near an exposed rock and begin our drift. Zimmerman probes down to 40 feet where, beneath the layer of murk, he sees the spectral outlines of hammerheads. He follows the sharks and signals us to follow him. Healey’s only halfway through his rest cycle, but the current will blow us off the school if we don’t move now. He dives, pauses to scan the water column four stories down, and continues toward the bottom. I trail, a minute behind and 30 feet above him, straight into a school hundreds thick.

They’re beautiful animals of inspired design—slate gray with a white underbelly, sleek and powerful, and wonderfully freakish. Their long, undulating brow is broken by right angles—they have a “divergent body plan,” as Gallagher describes it in one of his papers. The term hammerhead, if evocative branding, seems a misnomer. Flat and wide, the shark’s cephalofoil is more reminiscent of a chisel. Its mouth, usually the focus of hysterical phobia, is comparatively small and set downward, just north of its stomach, in the perfect place to feast on squid.

They move in concert, swaying through the water with silent grace. They are creatures that want to swim together and be left alone. Toward the center of the school, one of the larger females rolls on her side, flashing her pale underbelly in a mating display. Healey glides into the back of the school, takes aim at a seven-footer, and fires.

It’s a direct hit, right behind the dorsal fin, but it bounces off. With a few quick flicks of the tail, the shark disappears into the crowd. Healey grabs the tag as it sinks toward the bottom, then heads to the surface. He’d fixed the tag to the tip of the gun with a rubber band, which didn’t break. The setup needs tweaking, but Healey gets a second hammerhead before the afternoon wraps.

The last two days are an exercise in target practice. Healey tags Galapagos and hammerheads with both acoustic and satellite transmitters. The scientists set three more receivers, and by the time the typhoons wash Mikomoto in surge, we’ve tagged ten sharks and set five receivers—a successful tally for a year-one expedition being cut short by nearly a week.

The scientists’ plan for their remaining time in Japan: temples in Kyoto, ramen and skyscrapers in Tokyo. Healey’s got other ideas. Just about every big-wave surfer in the western Pacific has been watching the buoys, and tomorrow is calling for 30-foot surf near Chiba, about 40 miles southeast of Tokyo. Healey has a friend flying in from Hawaii with an extra nine-six. There’s a train leaving in an hour. His hair isn’t even dry from diving, but if he hurries he’ll be in Chiba by midnight. It’s the biggest swell Japan has seen in five years.

Outside correspondent Thayer Walker (@thayerwalker) is the cofounder of Ink Dwell Art Studio.