Disney can now track your laughter, smiles, gasps, and frowns inside those darkened cinemas.

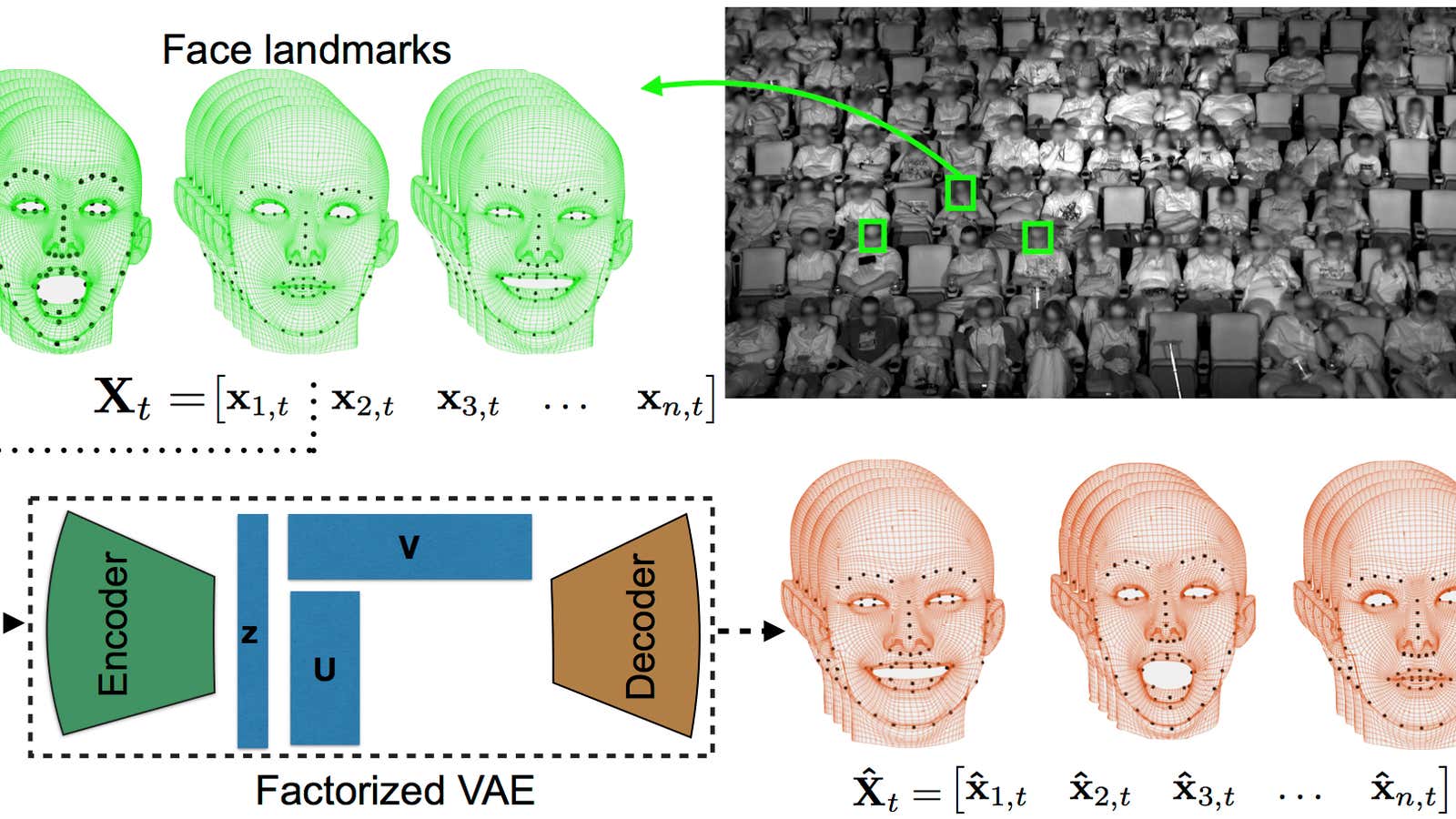

The media conglomerate’s research arm is using machine learning to assess the audience’s reactions to films based on their facial expressions, it wrote in a new research paper (pdf). It uses something called factorized variational auto-encoders, or FVAEs, to predict how a viewer will react to the rest of a film after tracking their facial expressions for a few minutes.

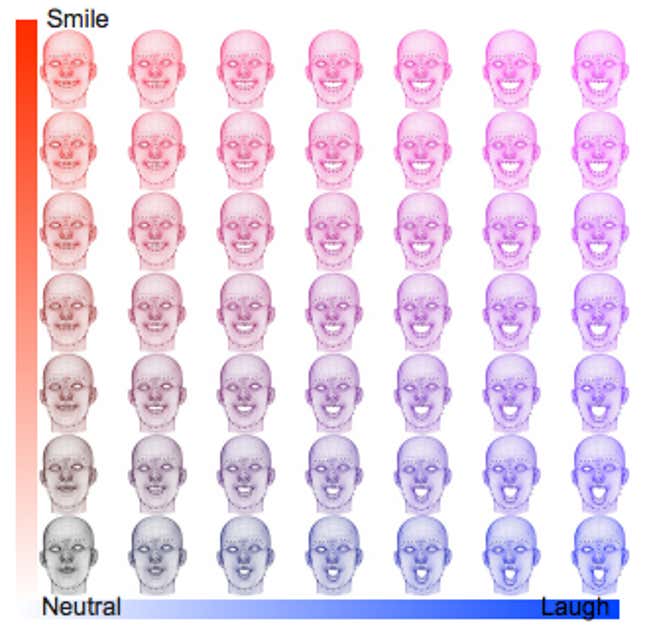

The FVAEs learn a set of facial expressions, such as smiles and laughter, from the audience, and then make correlations between audience members to see if a movie is getting laughs or other reactions when it should be—a much more sophisticated version of how Amazon and Netflix make suggestions for new things to buy or watch based on your shopping or viewing history.

By placing four infrared cameras and infrared illuminators above a theater screen, the researchers were able to identify 16 million facial landmarks, or expressions, from more than 3,100 theatergoers during 150 screenings of nine Disney movies, including Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Zootopia, and The Jungle Book during 2015 and 2016. The data was then analyzed with a computer. (Before this gets too creepy, Disney isn’t tracking your every move at your local theater. The experiment took place during screenings at one particular 400-seat theater. And audiences likely had to choose to participate.)

Disney’s new technology could help the movie studio get a better read on test audiences, who get to see films early in special screenings, and which have long been a staple of Hollywood. Movie studios alter or recut films when they don’t get the desired reactions from test audiences. That’s how E.T. got its uplifting ending: an early version of the 1982 film killed off the beloved alien, but test audiences detested it.

Filmmaker Paul Feig, of the comedies Ghostbusters and Bridesmaids, swears by test screenings, too. “I rely on test screenings like crazy,” he told audiences during the Tribeca Film Festival in April. “I’ll try to get in front of a test audience as soon as I can, usually like four weeks in, so that you’re not in love with it… You’re kind of like I think this is good, let’s try it, let’s see what’s working.”

These screenings tend to rely on self-reports from theatergoers, which the paper says “is not only subjective and labor intensive but also loses much of the fine-grained temporal detail, as it requires a person to consciously think about and document what they are watching, which means they may miss important parts of the movie.” Some studios outfit their audiences with wearables that track heart rates and other physical responses, like 20th Century Fox did with its gut-wrenching film The Revenant. But Disney says its vision-based approach is better, because it allows audiences to experience films they way they would naturally.

The research team told Phys.org that the method can be employed outside of the cinema as well:

If FVAEs were used to analyze a forest—noting differences in how trees respond to wind based on their type and size as well as wind speed—those models could be used to simulate a forest in animation.

That could be useful for Disney’s theme parks, which are becoming more realistic and immersive every day.