Last Friday, world attention was consumed by the meeting between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin. In Hamburg, Germany, the two men met as leaders of their respective nations for the first time.

The moment was fraught with significance as everyone wondered if Trump would broach the explosive subject of Russian meddling in the 2016 presidential election. The issue cuts to the heart of his legitimacy to lead the United States and Trump has been famously loathe to address it.

In the end, it happened, the question was asked. Putin said no, and the two leaders moved on.

While most of the world — including key U.S. intelligence agencies dismissed Putin’s denials, Oliver Stone is not so certain.

The Oscar winning filmmaker of such classics as Born on the Fourth of July and Platoon caused his latest stir with the Putin Interviews. The four-part Showtime series is dense affair covering more than 20 hours of conversation between Stone and Putin. That along with a companion book with even more material offer one of the most unvarnished looks let into mercurial Russian leader to date.

It’s far from perfect, but the footage is revealing and worth a watch.

“I went to Moscow because of the Snowden movie because Snowden was over there. Nine times actually,” Stone told Mediaite. “During one of those trips, I met Mr. Putin backstage at a theater … I met him backstage and we talked about Snowden. He was very forthcoming, bright, articulate, no tinpot dictator about it at all, very modest man. We followed up. We asked for the interviews.”

The rest was history — or at least Putin’s version of it.

While any American can Google around for established narratives of post-Soviet Russian history, Stone’s series takes viewers on a journey into the post-Cold War world through Putin’s eyes. From Crimea, to Chechnya, to NATO to the minutiae of antimissile systems — no issue of Russian geopolitics is left unexplored.

Stone, too, asked about those emails.

“We never interfere in domestic affairs of other countries,” Putin tells the filmmaker at one point in the series as a slight smile crosses his lips. On that central front, Stone was taciturn, suggesting to Mediaite that he was inclined to believe Putin.

“I think in some ways they don’t have the money for it,” he said.

As Masha Gessen pointed out in the New York Times, much of Putin’s narrative is false. Stone’s blithe acceptance of “facts” like that Russia has “hundreds of television companies” operating independent of the Kremlin, should have been rebutted. Same with a number of equally fantastical claims about Ukraine.

History, however, is often nebulous; colored in the eye of the beholder. As Gessen also pointed out on MSNBC, Putin exists in his own echo chamber and watches his own Fox & Friends. In fact, she says, he’s a lot like Trump.

“Both men are quite similar. They live in their information bubbles. They like their information bubbles. Trump actually is regularly exposed to much more irritants than Putin is.”

Understanding such a man and bringing his worldview to American audiences has its merits.

Nevertheless, it also lead to arguably the series’ biggest failing. Presenting Putin’s narrative and worldview is an interesting academic exercise, but for lay audiences, it becomes a dangerous example of accidental propaganda.

In this respect, Stone falls into what I humbly term, an Edgar Snow trap.

In 1936, Edgar Snow, another intrepid western chronicler, was given remarkable access to Mao Zedong and his guerrilla fighters. Fresh off their near extinction in the Long March, Mao cut a romantic figure. The leader of a ragtag band of patriots fighting for freedom against impossible odds was far more compelling than his Nationalist counterpart, the corrupt and decadent Chiang Kai-shek.

Americans were hardly predisposed to Communism, and Snow’s sympathetic book, Red Star Over China, normalized the future dictator to broad swaths of the U.S. population. The author stood by the Chinese autocrat even after his policies and purges left millions dead.

Here he is with Mao during a military parade in 1970.

Stone bristled at the very suggestion.

“Analogy is horrible,” he chided. “Mao was a different kind of person.”

While that is obviously true, the broader comparison is harder to dismiss. Whether or not it was Stone’s intention, his series paints an eerily favorable portrait of Russia’s leader. Like Snow in his later years, that unfailing support comes in the shadow of a few too many dead activists and journalists to hold water.

The access is groundbreaking and the series revealing, but Putin is no misunderstood Russian teddybear. No viewer should approach Stone’s work thinking otherwise.

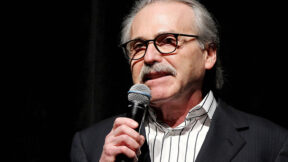

[image via screengrab]

Follow Jon Levine on Twitter / Facebook.

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.