Hong Kong’s Waglan Lighthouse: the light’s on, but nobody’s home

Dating back to 1893, the declared monument is now fully automated but its surrounding buildings are being left to crumble, as the great-granddaughter of the Briton who designed the structure discovers

Located 5.4 nautical miles southeast of Stanley, on a forbidding rocky island that is strictly out of bounds to the public, it must be the most romantic and least visited of Hong Kong’s 114 declared historic monuments.

The Waglan Lighthouse marks the southern approaches to Victoria Harbour. It and its compound were constructed by China’s Imperial Maritime Customs Service and completed in May 1893, when the island it stands on was not yet part of colonial Hong Kong.

Waglan is a rare example of a prefabricated cast-iron lighthouse from the 19th century – when lighthouse technology and specialist engineers in the field were revered in the same way that United States space agency Nasa is today.

Until the facility was automated in August 1989, the remote complex was home to a small team of dedicated operators, assistants and technicians who kept the light burning 24/7 in all conditions, including deadly typhoons. While the lighthouse still functions and is regularly maintained by the Marine Department, the rest of the compound – including former living quarters, machinery, offices and workshops – has been abandoned and left to the mercy of the elements.

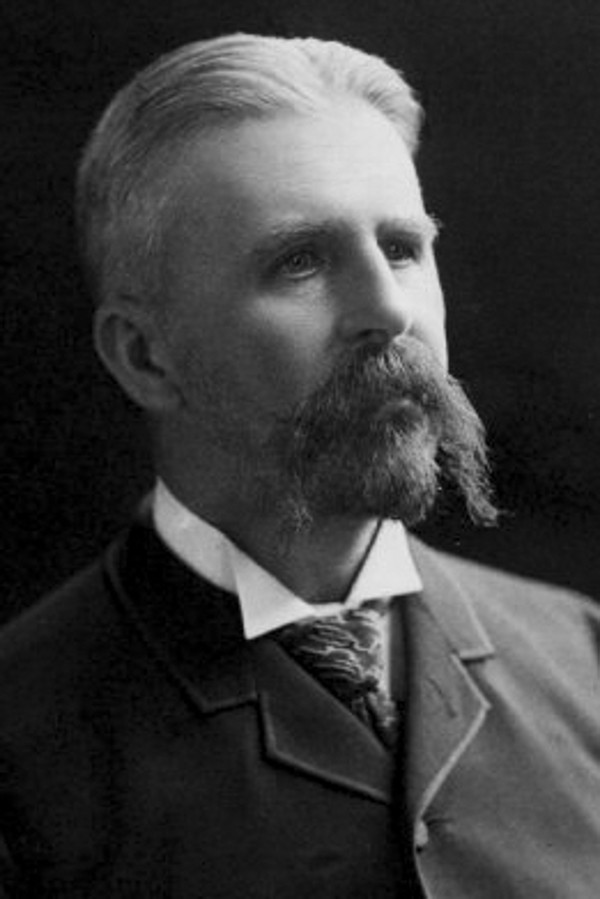

“It feels like Chernobyl – just derelict and neglected,” says a solemn Martin Cresswell, standing among broken windows, cracked concrete, overgrown vegetation and piles of rubbish in what was once the busy signal station. Cresswell is a marine engineer and one of a party of shipping professionals authorised to visit the complex as part of a trip organised by the Nautical Institute, an international body for professionals involved in the control of seagoing ships. Today they are accompanied by a special guest: Felicity Somers Eve, great-granddaughter of David Marr Henderson, or “DMH”, as she affectionately calls him, the man who designed Waglan Lighthouse. She and her husband have come from Britain to undertake a once-in-a-lifetime tour of China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, to see some of her ancestor’s constructions.

Marr Henderson was a colossus of 19th-century lighthouse engineering. When he joined the Imperial Maritime Customs Service in Shanghai, as its engineer-in-chief, in 1869, the 28-year-old was already renowned as an expert in lighthouse optics and engineering.

Headed by the formidable Sir Robert Hart, the customs service was responsible for all aspects of maritime operations in Qing-dynasty China, from buoys and pilots to the collection of customs fees. Hart believed that if China had a part to play in international shipping, it needed a network of state-of-the-art lighthouses, and many of Marr Henderson’s still adorn the coastline, stretching from Xiamen and Shanghai to the southern tip of Taiwan and the remote Penghu Islands, also known as the Pescadores, in the Taiwan Strait. His legacy in terms of maritime safety and engineering is unrivalled.

“We understand that the Engineer-in-Chief of the Imperial Maritime Customs (Mr-D Marr Henderson) has made a thorough examination of the Gap Rock, Reef Island and neighbouring sites,” reported the China Mail on March 28 of that year, referring to him with deference as “Mr Henderson whose ability and experience are certainly very great”.

The complication with Waglan, and with Gap Rock, built the previous year and now operated by Chinese authorities, was that it was not in Hong Kong waters, so the construction of this ambitious project was probably the first undertaken by Hong Kong to require collaboration, and cost-sharing, with China. Hong Kong authorities did not take it over until January 1901, three years after the New Territories and outlying islands were leased to Britain.

The formal handover, later the same year, was a big story for the local press, the China Mail reporting on March 2, 1901, that Basil Taylor, the acting harbour master, had taken over the light on behalf of the colonial government. It described three “Trinity House men from home” who were responsible for the operation of the light with “three Chinese assistants and three coolies”. Trinity House is Britain’s general lighthouse authority.

Operation of the light is now the responsibility of Branden Woo Po-keung, of the Marine Department, and 16 metres up the winding staircase of the red-and-white tower he and his two colleagues, Yeung Sin-ying and Chuen Lay-kam, are checking the light array.

“This light is still very important for navigation,” says Woo, who visits it about once a month for routine maintenance. The current light is about 20 years old and consists of a large array but, Woo adds, the backup is a new installation using the latest LED technology.

In Marr Henderson’s day, the light array, designed by French firm Barbier, Bénard & Turenne, was considered revolutionary. The light itself burned mineral oil and employed a novel mercury-bath rotating lens that offered an almost friction-free bearing for the apparatus, which enabled the eight-tonne structure to be rotated effortlessly and quickly.

It was the French company’s British rival, Chance Brothers of Birmingham, where Marr Henderson once worked, that introduced rotating-optics technology, allowing adjacent lighthouses to be distinguished from each other by the number of times per revolution their lights flashed. As all seafarers know, each lighthouse has its own fingerprint, or call sign, based on the number, timing and duration of the light flashes and dark periods (occults), so ship crews can correctly identify their position. Waglan’s light characteristic is listed as “Fl (2) W 20s”, meaning two white flashes every 20 seconds (originally it flashed every 30 seconds).

The walkway affords the party a fine view of the rest of the derelict compound.

On the roof of the machinery room, at the far end of the complex, two large conical fog horns – now disused, rusty and silent – are rapidly corroding. New diaphone fog signals were a source of great pride when they were successfully tested at the government workshops in Wan Chai, in April 1922. The system of explosive guns they replaced sounded no less than 2,108 times during 1909, but the new horns could warn ships up to 10 nautical miles away, and the two air-cooled reciprocating compressors and the diesel engine that powered them would have been maintained on a daily basis.

Look at the terrible state of that concrete – the cracks and exposed reinforcement. It’s probably too late to do anything now except knock it all down.

The machines and alternators that once supplied electricity to the light are still in place, but the gauges and controls are corroded and seized up from neglect. Members of the party discover spare parts still in their plastic bags, untouched for decades. A rusting winch is found partially concealed by overgrown grass. It once dragged stores up the rails of the pseudo-funicular railway that connected the compound with the landing stage. Before the tracks were laid in the 1970s, all fuel and supplies had to be carried up the steep steps on the shoulders of the lighthouse staff.

There is no natural water supply on the island, so water rationing was common. In May 1910, an acute shortage was relieved only when 22 tonnes of fresh water were pumped from the steam tender Stanley into the compound’s tanks.

Jimmy Deacon, former superintendent of navigational aids for the Marine Department, offers a rare insight into life as a lighthouse keeper in the post-war years at Waglan in an undated short account posted on the Nautical Institute’s website. “For years, we had difficulties in recruiting new lighthouse keepers, especially in the earlier days, because the crews that worked in the lighthouse had to be away from home for four weeks on each duty cycle,” writes Deacon.

Every other Tuesday was a “relief day”, he continues, when half of the crew could go home. These were “big days to them” and all staff, except the one man who had to keep watch in the now derelict signal tower, would be at the landing stage to welcome returning colleagues, receive news and gossip from the outside world and assist in transporting food, other stores and fuel.

Next to the lighthouse are the stone blocks of the staff quarters. Inside, a collapsed bed stands among the debris, the smashed windows and their rotten frames having allowed the elements to take their toll. In October 1909, a fierce typhoon flooded this accommodation block, despite its elevation. According to one local newspaper, “The cookhouse chimney was blown away and the chicken house carried into the sea.”

The building has housed generations of lighthouse crews, survived countless typhoons and even emerged from the second world war, when it was bombed by Allied aircraft, but it’s finally surrendering to years of neglect.

The mess room is, well ... a mess, with cracked concrete beams, peeling walls and ceiling lights lying abandoned on the floor. In the office in the same block, notices remain attached to the wall by drawing pins, informing staff of promotions and new safety protocols. One is signed by D. A. Hall, deputy director of marine, and is dated December 31, 1987.

Above the dormitories, mess room and office is the signal station. It was recorded in the Hong Kong Telegraph that during 1909, 2,168 vessels were reported and 2,348 messages were sent from here.

In addition to keeping the light burning and fog sirens operating, Hong Kong lighthouses such Waglan were important signalling stations, linking to the city via telegraph cable and with passing ships by use of Morse code light, flag signals and semaphore, until the wider use of radio after 1912.

“Look at the terrible state of that concrete – the cracks and exposed reinforcement,” says Cresswell, wistfully gazing out from the signal station. “It’s probably too late to do anything now except knock it all down.”

Historically, lighthouse keepers and their staff were renowned for the meticulous care they took of their isolated homes. Brass was relentlessly polished, equipment oiled and greased, flower beds trimmed and brickwork painted and repainted.

Today’s decay would have those keepers of old turning in their graves. And it’s difficult for members of the visiting party to reconcile the neglect with the lighthouse’s declared monument status – part of Hong Kong’s heritage that should be protected for future generations.

“It’s been really wonderful today, but if that is an example of Hong Kong protecting its local heritage, then ... oops,” says Somers Eve, when pressed on the matter.

Later, when the city’s Antiquities and Monuments Office (AMO) is asked to explain the condition of the buildings within the Waglan compound, a spokeswoman is brief.

“You must refer to the map of the declared monument shown on the AMO website,” she says, revealing that the monument site is defined only as the lighthouse itself and a small area of cliff to the west. It seems other historic buildings are not part of the official monument, and so have been left to rot.

“We do not have sufficient information to answer your question,” says the spokeswoman.

Marr Henderson worked for the Chinese Maritime Customs Service for some 20 years before retiring and returning to Britain, having been responsible for the construction of more lighthouses in Asia than anyone before or since. He died in East Sussex, England, in 1923, and a succinct obituary, published by the Hong Kong Daily Press on September 24 of that year, read: “The death is announced of Mr David Henderson at the age of eighty-three, former engineer-in-chief to Chinese Maritime Customs.”

While much of his legacy remains intact, the part of it at Waglan Island – also the working home of the brave, selfless men who operated his light from 1893 to 1989 – is crumbling away.

“It’s only when you are here [that] you realise what it must have been like for those lighthouse keepers and their staff,” says Somers Eve, as she boards the boat that will return the party to Central. “You have to admire their perseverance and ingenuity.”