Should some malevolent force decide to vaporise the work of all postwar British cultural historians bar one, we can but hope that the survivor is Robert Hewison. A critic, curator, academic and Ruskin scholar, Hewison has written five books that add up to a narrative not just of the arts and literature of the last 70 years, but also the historical background against which it was produced and the increasingly complicated means by which it was financed and brought to the public.

In Under Siege, Hewison explored the strange world of literary London in the war years. In Anger described how, from 1956, an exhausted yet hidebound “official” postwar culture was challenged by the angry young men of the theatre, cinema and fiction. Too Much charted the rollercoaster years of the 1960s, while Culture and Consensus went back to the beginning in 1940, taking the story forward to the Thatcher and early Major years. If his overall story has a headline, it would be “hierarchy of taste” being exchanged for “democracy of access”.

Between Too Much and Culture and Consensus, Hewison wrote a very different kind of book. His studies of 1940-1975 had been history recollected in tranquillity; in 1987, by contrast, he published a topical polemic against the phenomenon he identified and named as The Heritage Industry, that combination of ersatz country house nostalgia with aggressive shopkeeping (from the Brideshead Revisited TV series to the Wigan Pier Heritage Centre to Mr Kipling’s cakes) that was Thatcherism’s enduring cultural legacy.

Although effectively covering the 20-year era between the birth of New Labour and pretty much now, Hewison’s new book Cultural Capital is in The Heritage Industry mould. Here, he is not analysing cultural history so much as advancing a case. The argument is that, after 20 years of Thatcherite parsimony, the 1997 New Labour government offered the arts a Faustian pact. In exchange for a dramatic £290m hike in the government grant to the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (whose total budget was to pass the £1bn mark by 2001), the arts would be required to contribute to a (not very distant) post-Thatcherite agenda of marketised public services pursuing the government’s economic and social objectives. The mechanisms by which this was to be achieved included the redefining of the cultural sector as part of the “creative industries” (largely consisting of commercial enterprises in sectors such as advertising, architecture and IT), and a rebranding embarrassingly dubbed “Cool Britannia” (the term echoing, perhaps significantly, a flavour of Ben and Jerry’s ice-cream). Then, government spending on culture was to conform to the Treasury’s Green Book guidelines, which required spending impacts to be measured and monetarised (by mechanisms of “contingent evaluation”, which involved asking people what they’d be prepared to pay for the services of Bolton libraries or Durham Cathedral). While, percolating down a level, institutions such as the Arts Council were to require their clients to pursue government aims (combating social exclusion, for instance) and submit to a regime of targets, “indicators”, monitoring and inspection to make sure that these benefits were achieved, and at the lowest possible cost.

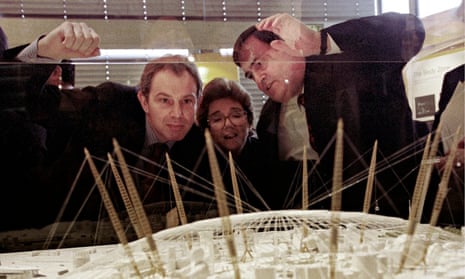

This strategy, Hewison argues, contributed to the catastrophe of the Millennium Dome, created a mountain of papers, proposals and reports (one, on the DCMS itself, titled The pale yellow amoeba), and provoked the Arts Council into a merry-go-round of frantic reorganisation (from devolution to regional arts boards, via recentralisation, back to devolution again), while such projects as the Public in West Bromwich and the Sheffield Centre for Popular Music foundered. A new logo for the Arts Council of England (dropping the “the” and the “of”) cost £70,000 and – according to chair Christopher Frayling – resembled a coffee-cup stain.

The mid-00s saw a minor revolt against all of this, led by the culture secretary, Tessa Jowell (oddly accused by Hewison of “brimming with a genuine, but at times overwhelming, sincerity”, as if sincerity was a characteristic in abundant supply in the political class). In 2004, Jowell wrote a “personal essay” criticising an instrumental approach to the arts. Her 2007 successor, James Purnell, proclaimed an end to “targetology”, commissioning a report from former Edinburgh festival director Brian McMaster that celebrated the intrinsic value of the arts (including the high avant garde), and proposed a major shift back from prioritising arts consumers to promoting the interests of arts producers.

Welcomed by artists, the anti-instrumentalist turn was shortlived. The following year, on the day that Damien Hirst’s Golden Calf was sold at auction for £9.2m, Lehman Brothers collapsed. Aware that justifying subsidy on the basis of art’s instrinsic value was going to be an ever-harder sell in straightened times, advocates turned to the concept of “public value” to square the intrinsic/instrumentalist circle. But arts spending was declining even under post-credit-crunch Labour; later, and unprotected by the ringfences that maintained spending on health and schools, arts spending under the coalition suffered a 30% cut. By 2016, the DCMS budget will be half as large as in 2010.

Finally, Hewison notes, the central New Labour objective of widening social access to the arts has not succeeded. Through the 00s, the DCMS and its clients had commissioned increasingly sophisticated surveys of arts participation and attendance. The most comprehensive, the Taking Part survey, found that, between 2005 and 2013, the arts audience increased by 2%, to 78.4% of the population. However, researchers noted that the 78.4% were attending as little as one arts event a year, while the “voracious” arts audience – regular attenders active in two or more arts domains – was as little as 4% of the population. The properly celebrated £25m funding uplift to regional theatres, implemented in 2003, had made such theatres more confident, optimistic, ambitious, diverse and attractive to talent, but the actual audience hadn’t increased at all. And all researchers agreed that the arts audience remained stubbornly whiter, older and more educated than the general population. True, the gap between the “high” and popular arts had narrowed: people who go to the opera are more likely to go to rock concerts, and vice versa. But the ambition to widen access to the arts had failed.

The fact that all those targets and milestones and barometers hadn’t brought about the desired effect is a dispiriting conclusion. With little about the actual arts of the 90s and 00s (though there is an excellent passage on the fine-art market), Cultural Capital is sometimes a drier read than some of Hewison’s earlier books. But as a polemic, Hewison’s analysis of how a golden age turned to lead is highly authoritative, well argued and conceptually robust (ah, there’s a New Labour word).

There are a couple of caveats. First, the sheer weight of managerial incompetence can blind us to the fact that some of the golden age was very golden indeed. Hewison acknowledges, perhaps a little briefly, that New Labour’s period in power saw not only the debacle of the Dome, but the renewal of the Royal Shakespeare Company, a period of unparalleled achievement for the National Theatre, the end of museum charges and the opening of Tate Modern and Sage, Gateshead. Surely, some of these achievements occurred because of rather than despite how they were funded.

Second, New Labour cultural policy was a significant departure from that of its predecessor. Hewison tends to lump the economic and social impact of the arts together as two heads of the same instrumentalist hydra, but encouraging the arts into schools, prisons and hospitals is a different – and you might say, more socially progressive – thing to encourage than counting the number of hotels and restaurants that get built near large cultural institutions in major cities. And while it’s certainly true that many arts organisations would have set up outreach and educational departments whether or not their funders had told them to, national policy has encouraged and sustained its clients in doing so.

There is one example of how national funding policy can achieve real outcomes over time that Hewison doesn’t address. Following its report into the effects of its 2003 increase in regional theatre funding, the Arts Council commissioned a further report into how the uplift had affected new writing. Always a Cinderella sector in the theatre (which always has the option of presenting plays by the dead), the Arts Council had encouraged theatres to do more new plays over many years, but in the 00s had stopped analysing the figures. The British Theatre Consortium (of which I’m a member) asked theatres regularly funded by the Arts Council about the plays they put on, and found that the proportion of new plays in the repertoire had increased from around 20% at the turn of the century to 42% by 2007–8. As a consequence, the traditional repertoire (classics and revivals of postwar plays) had proportionately declined. There’s an argument that some regional theatres had found it difficult to retain their traditional audiences while recruiting a new one. It appears however that, during the 00s, a huge move in the repertoire away from familiar old plays to risky new ones had been achieved with no decline in audiences. The Arts Council should regard that as a success story.

In a book so suspicious of instrumentalism, Hewison often seems wary of the idea that the arts do good. However, his book is replete with definitions of what art does to widen horizons, to expand perceptions, to question presumptions and to encourage empathy (as well as giving pleasure and delight). In his closing chapter, he adds to the list, arguing that the arts (in contrast to the market) provide people with a collective experience that “increases mutual tolerance, encourages cooperation and engenders trust”.

Published months before a general election, Cultural Capital comes at an excellent time to influence the thinking of the next government. The rhetoric of the current one has bounced between the three main contending arguments for arts subsidy: Jeremy Hunt promoting “arts for art’s sake”, Maria Miller prioritising “the value of culture to our economy”, and Sajid Javid arguing for increased access. In the same month as Javid’s speech, Labour’s Harriet Harman pointed out how precipitously primary schoolchildren’s participation in the arts has declined on the coalition’s watch. Getting the arts back into schools is one priority for any incoming government serious about the future of British culture. Another is to change the criteria by which arts funding is justified to the Treasury, basing it not on inevitably questionable evidence (or absurd attempts to put market prices on cathedrals) but on the undoubted if unquantifiable benefits the arts bring.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion