Anxiety

It’s Not Really About Control: Tips for Frustrated Couples

What’s the best way to resolve power struggles with your partner?

Posted August 9, 2017

It happens routinely. So often, when I begin counseling with a couple, not one but both parties complain that the other is trying to control them. And regardless of their partner’s conscious intention, that’s unquestionably their experience—and it's causing them considerable distress.

But the main problem in responding productively to such a grievance is that if there’s one simple explanation for almost every couple’s problems, that all-too-general rationale hardly delineates a clear path toward resolution. It’s just too inclusive. And it can’t possibly account for the deeper dynamics linked to the power struggle presumably creating the couple’s deep frustration.

In a sense, anything that can explain virtually everything ends up explaining nothing—or at least very little. To begin with, one partner’s definition of control can vary substantially from the other’s. But the main problem here is that the root of a couple’s difficulties might better be explained in other, far more revealing, ways.

For instance, what might it be about a partner’s behavior that actually makes the other anxious—and so prompts them to react “controllingly”? Or, what language might trigger a spouse’s “controlling” anger? And does this occur because almost anyone would find such words demeaning, or because what one partner said (however accidentally) reminded the other of disturbing verbal abuse from their past—and so activated never-fully-discharged acrimony from childhood? And so on.

What would happen if you were to recognize that your partner’s seemingly mean-spirited intent to control you might actually relate to their needing to quell in themselves such troublesome emotions as anxiety, grief, guilt, regret, shame, or hopelessness (emotions that, unwittingly, you provoked in them)? Would not such insight change the whole situation by enabling you to approach them differently?—in a self-respecting, yet more compassionate, manner? For in this scenario you’d simply ask them about their (assumedly, unintended) hurtful behavior—rather than attack them for it, or archly defend yourself from their outburst. Or, sulking (or maybe steaming!), abruptly remove yourself from them.

Note that, contrary to the way such conflicts are ordinarily viewed, the examples I’m providing identify the “triggered” partner not so much as the respondent to the other’s supposedly controlling behavior, but as the one initiating this behavior. And paradoxically, that individual is best understood as acting not offensively, though it certainly looks that way (and that’s undeniably its effect), but defensively.

For what they’re trying to fend off is the distressing emotion(s) that just got triggered in them—vs. expressing an incomprehensible hostility or malice, or consciously striving to manipulate the respondent to surrender to their dominant will. Moreover, in certain contexts they can take (or rather, mistake!) a mere suggestion as telling them that whatever they’re doing is wrong, or bad—and that unless it’s fixed they’re unacceptable.

Doubtless, the partner being spoken to so disapprovingly, or condescendingly, can easily be made to feel as though it’s their spouse who’s demanding they change, or do their bidding. And how could such a perception not result in the conclusion that their partner aims, degradingly, to control them? To an outsider, this cannot but appear to be a power struggle. But what’s really going on is something far less obvious, and far deeper.

Consequently, it may be not only wise but also pragmatic to consider that whatever control problems you’re having in your relationship need to be appreciated differently. For some, though admittedly not all, of your conflicts may have a lot less to do with control than (of all the supposedly simplistic terms!) comfort. That is, when you’ve said or done something that “betrayed” your separateness from your partner, it’s fairly predictable that, however irrationally, this discrepancy made them feel betrayed. Just below the level of awareness, this relational disparity upset their emotional equilibrium, suddenly inflicting them with such vague, inchoate feelings as fear or shame.

But, for now, let’s back up a little. Surely, we all have our preferred ways of doing things, and thinking about things. We might perceive things differently from our partner or, looking at the same evidence, draw opposite conclusions. Moreover, it’s only natural to desire that things go our way, or to make our own rules rather than follow someone else’s. So when your partner sees things differently, or wants things to go differently, that opposition can feel threatening and make you uneasy, irritated, or agitated. Not logically, but psychologically, it can even make you feel unloved.

In and of themselves, differences between you and your partner hardly need to be problematic, or render the relationship incompatible. After all (as, intellectually, you already know), such discrepancies are unavoidable. Really, just how sensible is it to assume that if you and your partner care about each other, the two of you will embrace the same beliefs, or have the same predilections? Nonetheless, however unconsciously, all too often that is what you assume.

So when your partner’s ways of being aren’t in sync with yours, on a deeply subliminal level it can feel invalidating, as though their differences somehow signify disapproval, even rejection, of you. That the mere fact of their diverging inclinations imply that you’re wrong, inferior, not acceptable.

Needless to say, such a deduction is flagrantly unreasonable. It’s a form of thinking that emanates from a much earlier, emotional child part of you. But (as I’ve stressed in so much of my writing for Psychology Today) when our feelings are powerfully aroused, our generally submerged child self pretty much takes custody of us. And that, for the adult still residing within you, can be most unsettling.

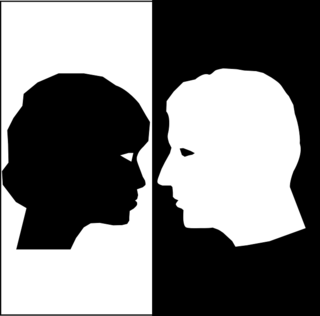

So, when this involuntary regression from adult to (black-and-white thinking) child begins to happen (i.e., before your adult self is totally “missing in action”), can you ask yourself why such understandable differences are so troubling to you? Why they’re engendering such disquieting feelings of distrust, suspiciousness, or foreboding—maybe even setting off crashing alarm bells inside you?

Obviously, to react this strongly is hardly commensurate with the situation. Nor is it helpful in resolving the immediate impasse between you and your partner. And it can't be overemphasized that what I’m talking about here isn’t one-way. For in the circumstances I’m describing, both of you are being triggered, both of you are feeling threatened—whether or not either of you can admit this to the other (or, indeed, to yourself!). Suddenly, you’re experiencing a worrisome vulnerability in the relationship that wasn’t there a moment ago. At the most primitive level, your sense of relational safety has completely evaporated. Without warning, your partner has “morphed” into your adversary.

As already suggested, the emotional reasoning fostering these reactions is almost never conscious. So, in the heat of the moment, it’s compellingly difficult to “reason” yourself out of these uncomfortable feelings. Instead, what you’re inclined to do is to employ a certain verbal aggression to impel your partner to relinquish their viewpoint and submit to your own.

You’re feeling much too “endangered” to make any serious effort to grasp their (contrasting) viewpoint—to reflect on it with curiosity, calm, and compassion; to seek to grasp it by considering how your partner’s personality differs from yours, how they were raised differently from you and subject to different influences. No, right now it feels as though if you were to understand—and validate—where they were coming from, you’d be forced to invalidate yourself. And having lost your mental composure, you’re no longer capable of distinguishing your viewpoint from who, essentially, you are.

. . . But if only you could take a deep breath and regain control of your emotions, that’s exactly how, non-antagonistically, you could approach your partner and begin to resolve such a conflict—or, more accurately, misunderstanding.

However, when you’re unable or unwilling to change your perspective toward your disagreeing (and so, disagreeable) partner, you’re far more likely to tell them that their position makes less sense than yours. In no uncertain terms, to inform them that they really shouldn’t think or feel this way, do something this way. That, frankly, their viewpoint is naive, wrongheaded, or ridiculous. And finally, that they really should think as you do—agree that your thoughts and feelings are more rational, more objective, more sophisticated than theirs.

And when, regrettably, you engage (indulge?) in such dogmatic discourse, how could your partner not feel controlled?

But still, you’re not—that is, not consciously—attempting to make them feel bad or hurt their feelings. Despite your critical tone and possible contentiousness, you’re merely trying to allay your own nervous, insecure feelings that have crept dangerously close to the surface. Nonetheless, your partner can’t help but react negatively to such impassioned, “controlling” communication, feel criticized and infer that your intentions must be to make them feel this way.

It’s extremely unlikely that, on their own, your partner would “get” that you were merely trying to alleviate your own anxieties, or restore your relational comfort to where it was before they (however inadvertently) triggered you. And regrettably, the end result of their offended reaction is to find some way of retaliating for your being so “controlling” toward them. For your behavior is experienced as manipulative, ill-tempered, coercive, and abusive. In other words, when they feel put down by you, what they’re most likely to do in return is something that will only exacerbate the conflict.

That’s simply how this so common, vicious cycle operates.

Certainly, the solution to all this is much easier for me to describe than for couples, mutually made anxious, to implement. For what’s required here is that both parties “revision” their differences in ways that reduce their subjective sense of threat. And an earlier article of mine—“You’re So Controlling!”—expands on this idea. That piece also includes the crucial caveat that if you’re in a relationship with a narcissist or anyone else who, consciously or not, regularly exploits and degrades you, you need to extricate yourself from it. Or—to safeguard your self-image from further deterioration—at least pursue counseling.

But if the situation isn’t that dire, then it may be time to talk to your partner about how you can better cope with your differences (and here, see my posts, “Can You and Your Partner Agree to Disagree?” and "To Accommodate or Confront: The Key Relationship Question"). And such coping involves finding ways to communicate that don’t lead either of your relational feathers to get reactively ruffled.

© 2017 Leon F. Seltzer, Ph.D. All Rights Reserved.