The Lifelong Learning of Lifelong Inmates

If reducing recidivism is the goal of prison education, what can be gained from teaching those who will be behind bars for life?

Lance leans over his desk, his round belly situating his body tightly between the wooden chair and plastic desk—both too small for someone with his girth. A collection of yellow notepad papers, their edges frayed after being torn from their original binding, wrestle alongside one another in his hands. It is a Saturday morning, and the classroom is small, and silent but for the friction of Lance’s papers and the grinding on the pen he bites out of nervous habit. His large fingers fiddle about the loose sheets, verifying that they’re in order as he mutters to himself, quietly reading his story aloud, restless in the anticipation of sharing with his classmates. Lance is often the first person to arrive in class, having rigorously prepared the entire week, perfecting his assignment so as to leave his peers impressed.

In this way, Lance is not so different from students I previously taught as a high-school teacher in Maryland. He is brimming with the sort of intellectual curiosity all teachers hope to see in their students. What is different is that this isn’t a high-school classroom: It’s a state prison in Massachusetts, and Lance is serving the 46th year of his sentence.

When his remaining four classmates arrive, they form a semicircle of five desks around me. Lance is a short, stocky man with olive skin, a shaved head, and uninhibited inquisition. Tyrus is tall with black, matted dreadlocks that fall to the middle of his back and a thick Caribbean cadence ornamenting his speech. Leo is built like a linebacker but laughs with the unrestrained whimsicality of a child. Chad has a thick New England accent, imbued with Bostonian bravado that juxtaposes his small stature. Darryl’s long salt-and-pepper goatee curls under his chin. His fingers trace the round frames of his reading glasses when a book passage presents him with an intellectual dilemma. Between the five of them they have spent 151 cumulative years in prison. It is unlikely that any of them will be released.

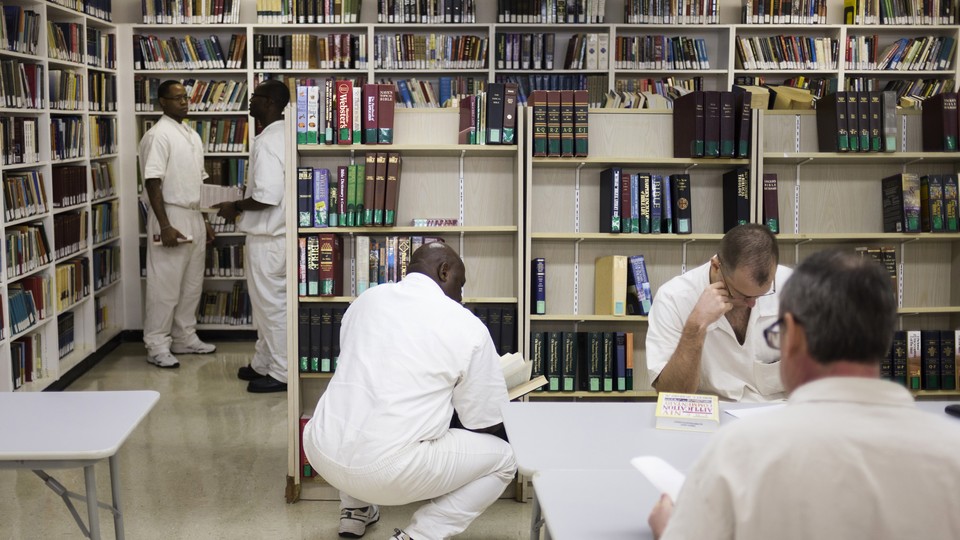

Policy circles tend to predicate the purpose of education singularly on reducing recidivism and increasing post-release employment opportunities. According to that line of logic, then, investing time and resources in individuals who will not be released is a waste. If the purpose of education for incarcerated individuals is instead understood as something that exists beyond social and vocational utility, then prisons take on new meaning. Perhaps prison educators and policymakers would more fully consider how such spaces serve as intellectual communities that restore human dignity within an institution built on the premise of taking that dignity away. In a recently published article for the Harvard Educational Review, I argue that providing education to incarcerated individuals should not be based on a myopic conception of efficacy; instead people in prison deserve education because the collective project of learning is and should be understood as a human right. The community of learners that Lance and his classmates have built has nothing to do with whether or not they will one day be released. (The names of the inmates referenced throughout this essay are the same pseudonyms I used in the aforementioned article.)

In one of our workshops the class reads an excerpt of Jhumpa Lahiri’s 2003 novel, The Namesake, a story that centers around the protagonist’s—Gogol’s—struggle to assimilate into “traditional” American culture as a first-generation Bengali immigrant. The novel, a fluid meditation on family and identity, found resonance with a group of men whose lives have, in many ways, come to be defined by the cages in which they’re kept. While Gogol’s existential struggle stems from straddling cultural bifurcations, Darryl’s stems from an effort to define himself beyond the criminal caricature the world has imposed on him. “Sometimes you get so caught up in how the rest of the world sees you,” he once remarked, “that you start to believe it.” The power of literature does not lie in resonance with the particular, but the way that the particular speaks to a broader, more universal truth. That an American-born black man who has spent decades in prison can see himself in the tale of a first-generation, Ivy-League Bengali immigrant speaks to how art, at its best, renders borders of difference obsolete.

That morning, moved by the book’s reflections on family, Darryl, serving his 43rd year in prison, wrote an essay. He described the despair of having the small moments—the ones that so often shape the contours of an individual’s relationships with loved ones—stripped away. An excerpt reads:

I am suffering in this place. Day after day, week after week, year after year, decade after decade, walking up and down hallways; going from room to room in the same building, under surveillance 24 hours a day.

The keepers start the kepts’ day off with the intercom announcement at five minutes to 7 a.m. “Five minutes to count! Five minutes to count!” The kept stir to life from a night of visiting who knows what or where, perhaps a dream of being home with mother and siblings or wife and children, sitting at the table to eat a meal of turkey, mashed potatoes with gravy, squash, and cranberry sauce. Then looking down to the end of the table and Taser in hand; turning around and seeing bars of the doorway which was not the same doorway he had entered through.

Silence filled the room after he shared his essay. Slowly, Leo began to nod his head. He looked towards Darryl. “Yea,” he said, pausing and then nodding for a few moments. “Thank you.”

To date, much of the research on prison education is centered on the correlation between prison education and recidivism—the tendency of an individual to reoffend. A 2013 meta-analysis by the RAND Corporation, in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Justice, found that incarcerated people who participated in correctional education programs have 43 percent lower odds of recidivating than those who did not. Furthermore, those who participated in such programs were 13 percent more likely to land post-release employment than those who had not. That number would likely be higher if discrimination against the formerly incarcerated weren’t so profound.

These data are compelling, but they disregard the fundamental role of prison education. Education is a human right—a recognition of dignity that each person should be afforded. It isn’t merely something that attains its value through its presumed social utility—or, worse, something that society can take away from an individual who’s convicted of breaking the social contract. That’s true even for the men I work with, nearly all of whom are serving life sentences, as are nearly 160,000 other people across the country for crimes ranging from first-degree murder to stealing a jacket. This reality—that those I taught would never leave the prison’s premises—recalibrated my understanding of the purpose of prison-education programs. Do those serving life sentences deserve access to educational opportunities never having a future beyond bars? The answer is yes and necessitates that in-prison education serves additional goals beyond reducing recidivism.

For Jill McDonough, a creative-writing professor at the University of Massachusetts who has taught in prisons throughout the state for the past two decades, prison educators and researchers should consider what education can provide that might not fit neatly into a spreadsheet. “I don’t need prison education to have quantifiable outcomes. I understand our incarcerated populations are our responsibility; we decided they don’t get freedom,” she told me, emphasizing that the criminal-justice system cannot simply remove people from society without subsequently providing them with the services they need. “If I were in prison, I’d want to take classes, to sit in a group of like-minded people excited and scared to challenge ourselves, to be able to give myself over to the work.” For McDonough, focusing too intently on quantifiable outcomes obscures what the essence of education, in prison or otherwise, is truly about. “I have been able to teach someone with a life sentence to write a sonnet, to hear that they worked on it with such focus that hours slipped by,” she continued. “That’s enough.”

Arthur Bembury, who is formerly incarcerated and now serves as the executive director of Partakers, an organization that provides mentorship to incarcerated men and women participating in the Boston University Prison Program, echoed McDonough’s belief that those serving life sentences shouldn’t be left out of the conversation around carceral education. “A lot of people ask why do we accept lifers into our program, if they’re not getting out? Why are we putting our resources behind somebody that doesn’t have a rap date?” he said. “One is: It instills a culture of dignity. And two: Lifers are a force within the prison system where they mentor other people.”

Substantial social science demonstrates the efficacy of offering educational programs that are not geared toward vocational output, or even reducing recidivism. Prison-education programs focused on art and literature, for example, keep prisons safer, as people are less likely to engage in violence when they have there is something meaningful and edifying to look forward to.

Education, whether inside or outside of a prison, creates its value in ways that aren’t always simple to measure. Nor should they be. One does not read a poem by Gwendolyn Brooks with hopes that it will grant him a career in engineering; he does so because poetry helps him see something in the world that he might not have seen before. One does not read an essay by Ralph Waldo Emerson because it statistically enhances her likelihood of staying out of the criminal-justice system; she does so because there is something to be gained from reading literature and exchanging ideas that tell her something about who she is in the world.

In a political moment defined by its obsession with cutting programs that “[sound] great” but “don’t work,” McDonough’s words may prove particularly essential: Committing to a set of values that may not reveal themselves neatly on a spreadsheet is just as important as adhering to the values that are easiest to calculate and assess.

These men are not perfect. They are complicated. They have made mistakes. In other words, they are human. And it is precisely this humanity that demands a space where they can ask and question and create and grapple with all that makes the world what it is—a place where social and intellectual community might be restored in a way that reestablishes an individual’s agency. The agency a carceral institution inherently attempts to strip away.