What You Had To Do To Hook Up In The Victorian Era

Do Not Try To Make Love To Every Woman You Meet

Photo: Boston Public Library / Flickr / CC-BY 2.0This is sound advice regardless of the era you live in, right? But it’s important to note that this pearl of wisdom from The Marriage Guide for Young Men: A Manual of Courtship and Marriage (1883) isn’t referring to intercourse. “Make love” to Victorians meant instead chaste courtship or wooing. This advice is offered under a heading titled “Do not carry your politeness too far.”

Gentlemen were advised to not assume that “every young lady is ready to fall in love with you.” It goes on to say that when you do find a lady ready to “make love,” you should “maintain a dignified reserve” or else your behavior will “belittle you in the eyes of sensible people, and perhaps spoil your prospects for desirable match.” In other words: keep it together, Pepé Le Pew.

Accepting Presents From Gentlemen Is A Dangerous Thing

The Young Lady’s Friend (1837) advises young ladies that accepting presents from guys will lead them on. “Some men conclude from your taking one gift that you will accept another, and think themselves encouraged by it to offer their hearts to you,” the reasoning goes, setting up this rule of thumb: “Make it a general rule never to accept a present from a gentleman.” Never? That’s harsh. Why? “You will avoid hurting anyone’s feelings, and save yourself from all further perplexity.”

What about anonymous gifts from dudes? Surely those are okay, right? Nope: “When this is the case, it is a good way to put them by, out of sight, and never to mention them.”

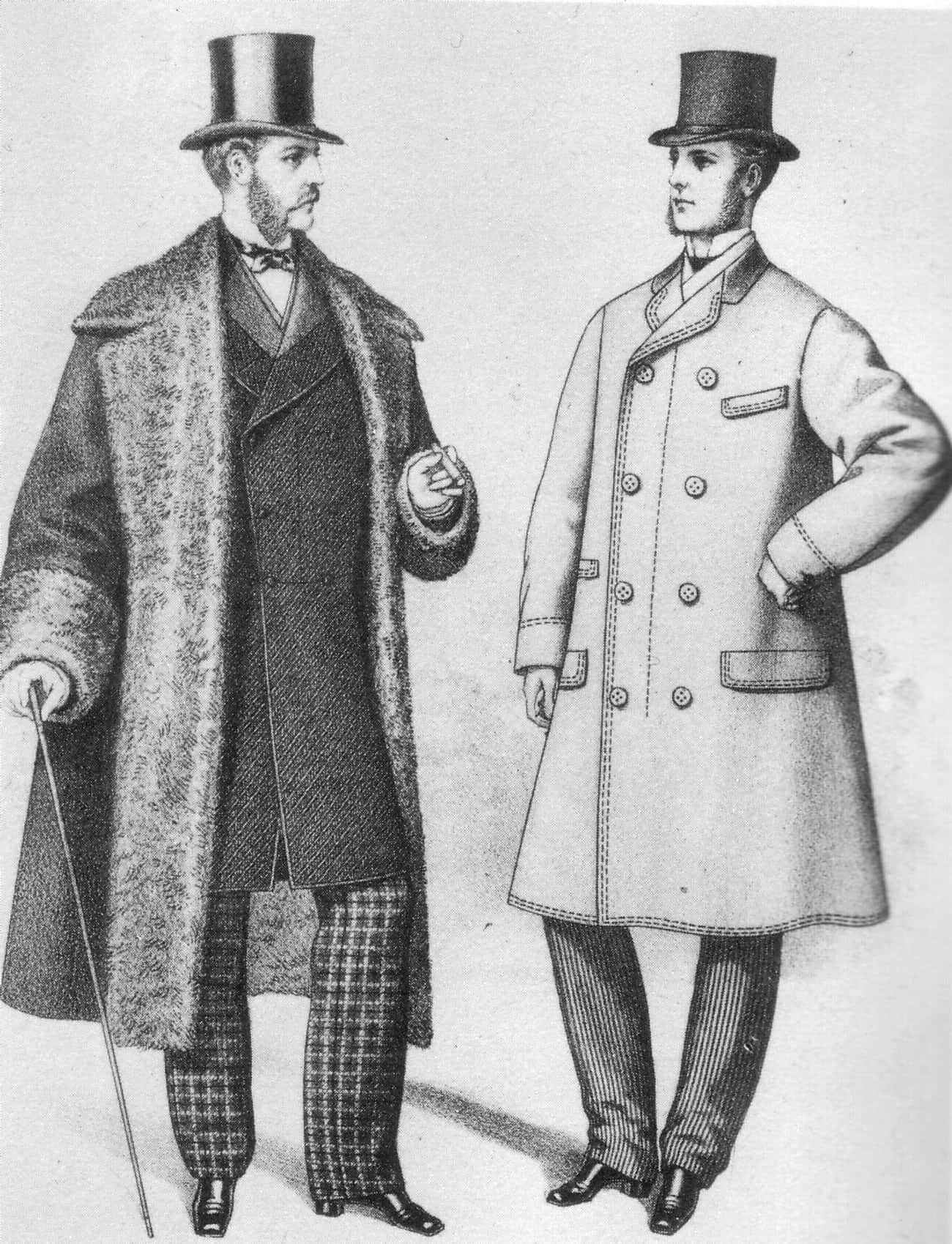

Be A Thorough Manly Man

Photo: Unknown author / Wikimedia Commons / Public domainThe author of The Marriage Guide for Young Men: A Manual of Courtship and Marriage (1883) doth protest too much, methinks and advocates for men to be “thorough manly men,” since “nothing can take the place of true genuine manhood.” (Nothing!) Women, it is argued, prefer a “backward, awkward, and even a little uncouth” manly man over a “polite, agreeable dandy.” Men of the time were told to not frequent “the haunts of disreputable women” or spend time “ruining weak-minded girls,” but instead “harden your hands and smut your face at honest work.”

In case the message wasn’t clear, the book also advises men to “engage in every manly exercise, so that all who look upon you will be compelled to say, ‘There is a man.’”

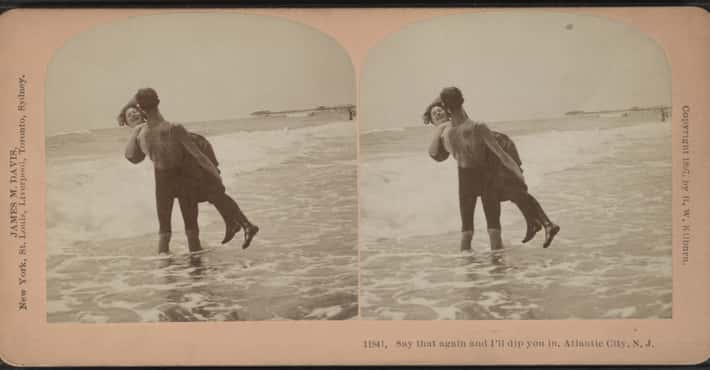

In Public, A Gentleman Should Show Constant Attention To His Intended

Photo: Edmund Leighton / Wikimedia Commons / Public domainCassell’s The Hand-book of Etiquette (1860) says engaged men should not only “show constant attention” to their “bride-elect,” they should also “neither in company nor elsewhere... flirt with any other lady.” Sound advice, right? But there’s a Victorian twist: “On the other hand, he should avoid, even to his bride-elect, those marked attentions and endearments that would excite in strangers a smile of ridicule.”

So no public displays of affection? Bummer. Then there’s this: “Engaged lovers may exchange portraits, presents, and locks of hair.” So no PDA, but please: exchange hair.

A Lady Never Calls On A Gentleman

Photo: Edmund Leighton / Wikimedia Commons / Public domainDecorum: A Practical Treatise on Etiquette and Dress of the Best American Society (1882) is very clear on this point: “It is not only ill-bred, but positively improper to do so.” The only exceptions are of the non-romantic variety; i.e., “professionally or officially.”

Men, however, have a bit more freedom, especially if the lady is already spoken for: “Gentlemen are permitted to call on married ladies at their own houses.” But there’s a catch: “never without the knowledge and full permission of husbands.” Surely that rule was never abused, right?

Be Ready To Act The Knight If A Lady In Your Company Is Attacked

Photo: Edmund Leighton / Wikimedia Commons / Public domainChivalry was very much alive and well in the Victorian era, it appears, with this weird nugget from Beadle’s Dime Book of Practical Etiquette For Ladies and Gentlemen (1859) dealing with verbal “attacks.” Interestingly, the advice also touches on what to do if a “lady in your company” is the one who started the trouble: “If she give offense, and that without reason, your office is that of mediator. You should even ask pardon for your companion.” Is this advising you throw your lady under the bus (or the Victorian equivalent)? Sort of!

The advice continues: “It is absurd to get into a quarrel for the sake of maintaining that a person who is insolent [i.e., the attacker] has a right to be so.” So if your lady is starting fights with men on the street for no good reason, apologize for her, but don’t take the attacker’s side too strongly: “You will show yourself, in acting thus, as ill-bred as he.”

An Introduction For Dancing Doesn't Constitute A Speaking Acquaintance

Photo: Louis Haghe / Wikimedia Commons / Public domainRules of Etiquette & Home Culture: Or, What to Do & How to Do It (1893) advises men and women to remember: dancing with one another doesn’t give you the right to speak to one another. It’s a ballroom, not a brothel, right?

This refers, specifically, to when men and women are introduced for the first time “at a ball for the purpose of dancing.” So if they’ve never spoken to each prior to the dance, it’s rude to talk during the dance or even after; it’s only polite to speak once the hostess has made formal introductions. The duo may, however, acknowledge each other before that time: “They are at liberty to recall themselves by lifting their hats in passing.”

When Traveling With A Lady, Always Carry Her Bag

Photo: Edmund Leighton / Wikimedia Commons / Public domainPaul Ryan would have loved the Victorian era. When the Republican House Speaker condemned Donald Trump’s infamous Access Hollywood tape in 2016, he said that “women are to be championed and revered,” a sentiment very much in line with Victorian-era etiquette: “For your own sake reverence woman wherever you find her; it will confirm you in the habits of a gentleman, and may be the means of winning you a genuine matrimonial prize.” (Champions typically get prizes, right?)

Part of “championing” a Victorian woman was carrying her stuff, as The Complete Bachelor: Manners for Men (1896) advised: “When traveling with a lady, always carry her bag and assist her in and out of trains.” This is, in fact, especially advised while traveling, since travel brings out “both the good and evil attributes of a man” and his behavior “is on its mettle under these circumstances.”

Women May Have Some Excuse For Coquetry, But A Man Has None

Photo: Edmund Leighton / Wikimedia Commons / Public domainThe Illustrated Manners Book: A Manual of Good Behavior and Polite Accomplishments (1855) reminds men to not act like women and exhibit trifling flirtations: “No gentleman should permit a lady, whom he likes, but does not love, to mistake for one hour the nature and object of his intentions.” Women are allowed “coquetry,” but men have no excuses for such womanly behavior.

Interestingly, the blame is subtly shifted away from the man and onto the woman and her friends: “To allow an innocent girl to deceive herself, or, as is more commonly the case, to be deceived by the badinage [humorous or witty conversation] of her companions, into the idea that you are her lover, and intend to propose marriage, is ungentlemanly.” So it’s ungentlemanly to flirt with a woman you like but don’t love, but most often the woman’s friends deceive her or she deceives herself. So no biggie.

But the advice takes a bizarre turn, warning of “two results” of this ungentlemanly behavior: “Either, having engaged the affections, and excited the hopes of the lady, you will feel compelled to marry her, or you will be disgraced, possibly cowhided [whipped], or shot.” You’ve been warned: flirting could get you killed.

In Walking With A Lady, Leave Her The Inner Side Of The Pavement

Photo: Edmund Leighton / Wikimedia Commons / Public domainBeadle’s Dime Book of Practical Etiquette For Ladies and Gentleman (1859) is just one of many Victorian etiquette books pushing this one, which has survived into the 21st century. While not made explicit in Beadle’s, the idea is to keep the lady from being exposed to unpleasantries from the street, such as water from splashed puddles and runaway carriages.

In 1922, Emily Post added a brief addendum to this, clarifying what a man should do if he’s fortunate enough to be walking with two ladies: “A gentleman, whether walking with two ladies or one, takes the curb side of the pavement. He should never sandwich himself between them.”

Neither Party Should Try To Make The Other Jealous

Photo: Edmund Leighton / Wikimedia Commons / Public domainThis is one of a few pieces of Victorian dating advice that is 100% still applicable today. The Ladies' and Gentlemen's Etiquette: A Complete Manual of the Manners and Dress of American Society (1877) says “Such a course is contemptible; and if the affections of the other are permanently lost by it, the offending party is only gaining his or her just deserts.” In other words, they got what was coming to them, which is a sentiment that has survived for centuries, right?

The entire “Lovers’ Quarrels” section is a barn burner, actually: “No lover will assume a domineering attitude over his future wife. If he does so, she will do well to escape from his thrall before she becomes his wife in reality. A domineering lover will be certain to be more domineering as a husband.” Preach it! “Neither should there be provocation to little quarrels for the foolish delight of reconciliation.” Wait: is this anti-make-up sex?

A Man Should Never Make A Declaration In A Jesting Manner

Photo: Alexander Jakesch / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA 4.0Our Deportment: Or, The Manners, Conduct, and Dress of the Most Refined Society (1880) warns against trifling with a lady: “It is most unfair... He has no right to trifle with her feelings for mere sport, nor has he a right to hide his own meaning under the guise of jest.” Similarly, a lady shouldn’t give a suitor “false hopes” and leave him “restless and unsettled.”

It’s interesting how the advice frames trifling behavior as affecting the sexes in wildly different ways. Women will have hurt feelings, reasonably enough, but men, apparently, will also act out: “It may cause him to express himself or to shape his conduct in such a manner as he would not dream of doing were his suit utterly hopeless.”

Should He Show Disrespect Toward Women, Repel All Advances

Photo: Anonymous / Wikimedia Commons / Public domainThis is undoubtedly great advice, but Maud Cooke, the author of Manners and Customs of Polite Society (1896), sort of ruins it by lumping her fellow women in with horses and “business pursuits.” Here’s how Maud throws ladies under the bus carriage:

[S]hould [a man] show disrespect toward women as a class, sneer at sacred things, evince an inclination for expensive pleasures in advance of his means, or for low amusements or companionship; be cruel to the horse he drives, or display an absence of all energy in his business pursuits, then is it time to gently, but firmly, repel all nearer advances on his part.

Gently! Sounds like men could get away with a lot before being slapped with a glove.

The guy sounds like a real jerk, Maud. But “disrespect toward women as a class,” “cruelty to the horse he drives,” and, especially, “absence of all energy in his business pursuits” shouldn’t be on the same “dealbreaker” level, right?

Parents Should Be Familiar With Their Daughter's Associates

Photo: Boston Public Library / Flickr / CC-BY 2.0Our Deportment: Or, The Manners, Conduct and Dress of the Most Refined Society (1879) advises parents to be “perfectly familiar” with their daughter’s associates and suitors, which sounds reasonable enough, but there’s a Victorian twist. These daughters, of course, have no self-control whatsoever: “In regulating the social relations of their daughter, parents should bear in mind the possibility of her falling in love with any one with whom she may come in frequent contact.”

The advice continues, advocating the shunning of any guy in your daughter’s orbit that is “particularly ineligible,” whether he’s interested or not, suggesting that the poor hypothetical schmuck “be excluded as far as practicable from her society.”

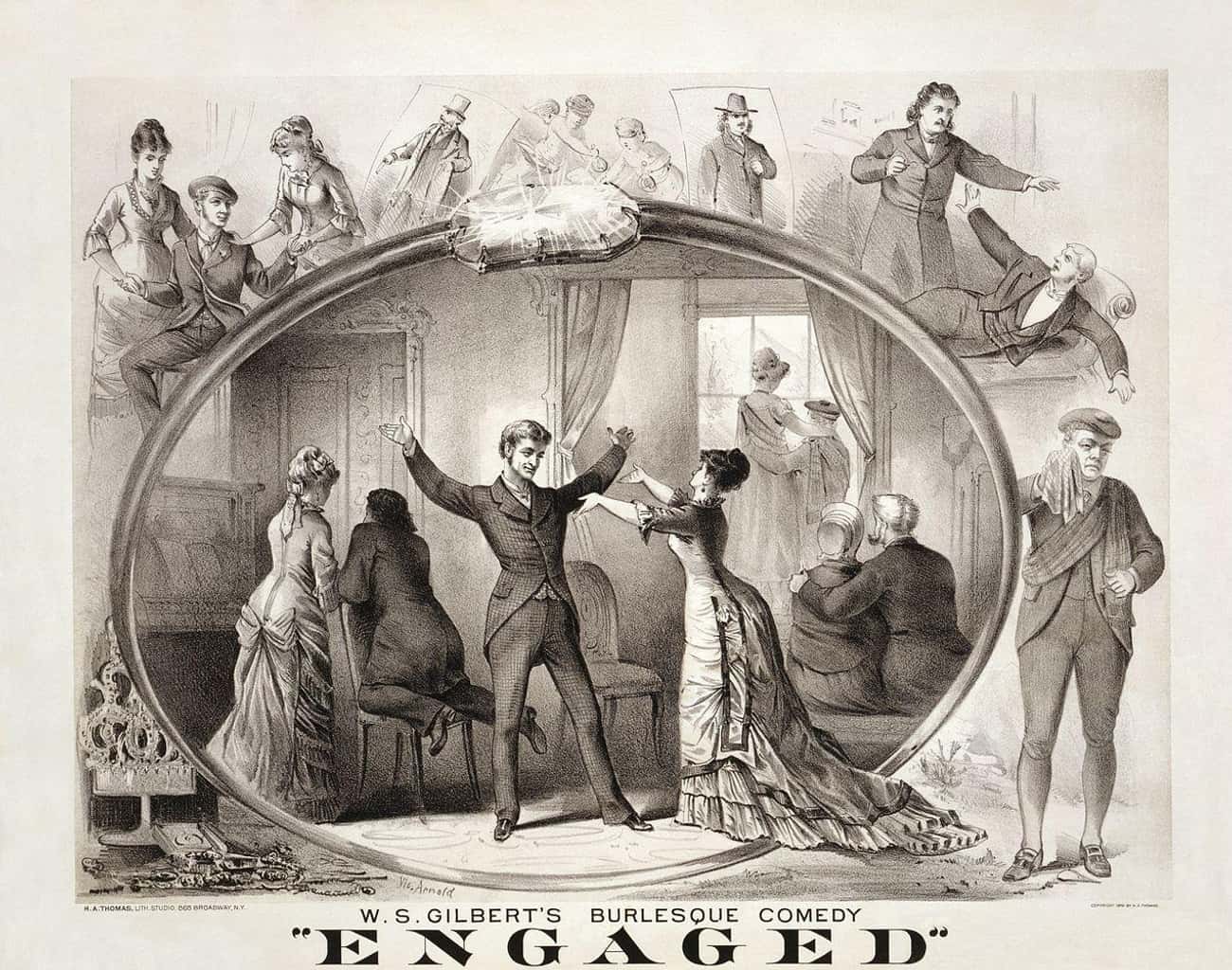

Manifest Whatever Qualities You Would Awaken

Photo: H.A. Thomas Lith. Studio, 865 Broadway, N.Y. Signed: Vic. Arnold/Restoration by Adam Cuerden / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY 3.0Orson Squire Fowler’s Creative and Sexual Sciences (1870) features a section called “The Great Secret - How to Elicit Love” aimed at men with this cross between The Golden Rule and The Secret, explained as “You inspire in the one you court the precise feelings and traits you yourself experience.” Fowler calls it “as sure as gravity itself,” claiming that a gentleman suitor’s success “must come from within, depends upon yourself, not the one courted.”

This blatant disregard for the feelings of women continues in a section titled, hilariously, “Anglo-Saxon Love-Making Errors,” which sounds like what would happen if you let a robot name a Bon Iver album. Fowler claims that God creates women to meet the needs of men: “The choosing one [the man, duh] should think the one chosen [the pretty lady] the most perfect and best for them obtainable, and ‘thank God for having created one thus perfectly adapted to their precise needs.’”