While venture investing outside the U.S. has come a long way in recent years, our analysis shows it remains an entirely different industry than U.S. venture capital. And when we say different, we mean totally different.

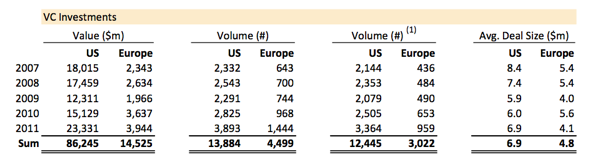

We looked at venture investment trends in 2007-2011 from PitchBook and compared them with VC exit results in 2012-2016 to very roughly compare investment in one five-year period with exit results in the ensuing next five years, roughly matching VC investment cycles.

Investment trends show “what you would expect”

Over 2007-2011, European venture started to accelerate. Of course, the industry remained a fraction of the U.S. in size, but by 2011 there were 1,400+ European investments made versus just under 4,000 in the U.S., a healthy jump in activity. And average round size was nearly $5 million versus $7 million for the U.S. — all indicative of a European VC industry developing rapidly from a much smaller base.

Exit trends point to entirely different industries

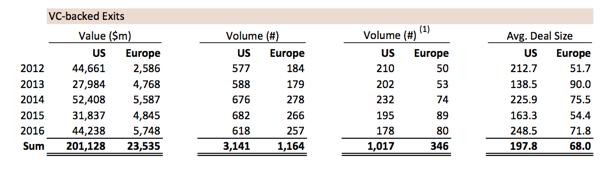

The subsequent five years, 2012-2016, show entirely different exit profiles. It’s encapsulated in a single number on the bottom right of the chart below:

The average U.S. venture capital exit is nearly $200 million, versus $70 million for Europe.

The number of $250 million exits during this five-year period? 22 across all of Europe, versus 166 in the US. That’s a huge, persistent disparity, especially given the evolution of European venture over the past decade.

What’s going on?

While European venture has come on leaps and bounds, it remains a “smaller round, smaller exit” market.

It is extremely dangerous for European earlier-stage VCs to raise ever-larger funds, or early-stage European companies to take very large A or B rounds. The European exit market is still far less developed, and putting more into companies can only damage returns.

The above has nothing to do with ambition, it simply reflects a current reality slowly changing; to make significant returns, CEO’s and investors need to invest less into more capital-efficient businesses that can return enough in a smaller, though successful exit.

A “good” exit in Europe is $100 million or more, while a “good” exit in the U.S. is at least $250 million.

What’s to be done?

The key is to fill the Series C “black hole” that currently exists for European tech. This will give the most ambitious CEOs and investors the opportunity to tap late-stage capital to accelerate beyond the $100 million exit mark, in turn creating more future unicorns in Europe; currently Europe has 1/10 the U.S. number.

Here are specific, feasible actions that can address this gap in a reasonable time frame:

- Extend the success of tax-advantaged investing to larger rounds. The U.K.’s EIS scheme has fueled unprecedented growth in Series A funding. Extending that and similar schemes around Europe to larger later rounds will undoubtedly increase the available capital for the most promising “scale-up” companies.

- Introduce specific government financing/co-funding for Series C rounds. It is very possible to do this via attractive debt instruments, as later-stage companies are often profitable and able to fund low-interest debt. For example, if each €15 million-plus equity round qualified for a €5 million matching government debt instrument priced at a very low interest rate, overnight it will increase the larger round market, and leverage even greater gains for late-stage investors, in turn bringing more capital to Series C and later rounds.

- Increase the number of highly skilled worker visas available for tech scale-ups. Europe has inherent advantages versus Silicon Valley; more stable workforce, far less current hostility to immigrants and a long tradition of numerous high-quality engineering schools. Adding to that a large scale inward “genius visa” program like H-1B in the U.S. will enable companies raising Series C to have confidence they can recruit the volume of engineers they need quickly, in turn making it even easier to raise their rounds.

- Create smaller “scale-up hubs” along the lines of “startup hubs” springing up around Europe. There is no shortage of European incubators, hot-desk workspaces and other types of “startup hubs,” but all cater to companies just starting. A more sophisticated and smaller scale set of “scale-up hubs” catering to 100+ employee companies, where more advanced mentoring and selective support is available, could spread experience and know-how to aspiring CEOs, and reduce scale-up and financing risks significantly. These hubs would be much smaller than startup hubs as they would cater to a few dozen CEOs, not a few hundred, and be aimed at filling the experience and mentoring gaps that can otherwise undermine large capital raises.

Without specific actions, the industry will need 20-30 years to evolve toward U.S. levels. With specific actions, we think this can be cut to perhaps 10 years.

Shortening this time horizon could perhaps create 10-20 more future tech unicorns, adding perhaps $50-100 billion of future aggregate economic value to European tech.

Now that is an attractive return on investment.