A congressionally mandated healthcare industry task force has published the findings of its investigation into the state of health information systems security, and the diagnosis is dire.

The Health Care Industry Cybersecurity Task Force report (PDF), published on June 1, warns that all aspects of health IT security are in critical condition and that action is needed both by government and the industry to shore up security. The recommendations to Congress and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) included programs to drive vulnerable hardware and software out of health care organizations. The report also recommends efforts to inject more people with security skills into the healthcare work force, as well as the establishment of a chain of command and procedures for dealing with cyber attacks on the healthcare system.

The problems healthcare organizations face probably cannot be fixed without some form of government intervention. As the report states, "The health care system cannot deliver effective and safe care without deeper digital connectivity. If the health care system is connected, but insecure, this connectivity could betray patient safety, subjecting them to unnecessary risk and forcing them to pay unaffordable personal costs. Our nation must find a way to prevent our patients from being forced to choose between connectivity and security."

At the same time, government intervention is part of what got health organizations into this situation—by pushing them to rapidly adopt connected technologies without making security part of the process.

The report, mandated by the 2015 Cybersecurity Act, was supposed to be filed to Congress by May 17. However, just five days before it was due, the WannaCry ransomware worm struck the UK's National Health Service, affecting 65 hospitals.

"The HHS stance is pretty much that we got incredibly lucky in the US [with WannaCry], and our luck is going to run out," Joshua Corman, co-founder of the information security non-profit organization I Am The Cavalry and a member of the task force, told Ars. The report was delayed by the WannaCry outbreak, Corman said, who observed that the task force members were disappointed that they hadn't gotten the report out sooner: "because if the report had been out a week or two prior to WannaCry, you could have bet that every Congressional staffer would have been reading it during the outbreak."

The task force was co-chaired by Emery Csulak, the chief information security officer for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and Theresa Meadows, who is a registered nurse and chief information officer of the Cook Children's Health Care System. The task force also included representatives from the security industry, government and private health care organizations, pharmaceutical firms, medical device manufacturers, insurers, and others from the wider health care industry—as well as healthcare data journalist and patient advocate Fred Trotter. Corman said that the task force was "probably the hardest thing I've ever done and maybe the most important thing I'll ever do—especially if some of these recommendations are acted upon."

But it's not certain that the report will spur any immediate action, given the current debate over healthcare costs in Congress and the stance of the Trump administration on regulation. Even so, Corman explained:

When we were working on this, we realized that if it was summarily ignored by the next administration, or if it was ignored for being too costly, the report could still be a backstop—in that when the first crisis happens, this will be the most recently available report that will be the blueprint for what to do next. It's just an indicator of how many minutes to midnight we are on this particular clock—we may be out of time to get in front of it, but we can certainly try to see which of these measures can be put in place in parallel [with a security crisis].

Brace for impact

The ransomware attack on Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center, which happened just a few weeks after President Obama signed the legislation that established the task force, helped establish the urgency of the work the group was doing (Ars' coverage of the ransomware attack is cited in the task force's final report). At the task force's first in-person meeting in April, Corman said he brought up the Boston Marathon bombing. "I said, imagine if you combined something like this physical attack with something like the logical attack [at Hollywood Presbyterian]." The impact—disrupting the ability to give urgent medical care during a physical attack—could potentially magnify the loss of life and shatter public confidence, he suggested.

The recommendations generated by the task force amount to a Herculean to-do list:

- Define and streamline leadership, governance, and expectations for health care industry cybersecurity.

- Increase the security and resilience of medical devices and health IT.

- Develop the healthcare workforce capacity necessary to prioritize and ensure cybersecurity awareness and technical capabilities.

- Increase health care industry readiness through improved cybersecurity awareness and education.

- Identify mechanisms to protect research and development efforts, as well as intellectual property, from attacks or exposure.

- Improve information sharing of industry threats, weaknesses, and mitigations.

That list is no short order. And it may already be too late to prevent another major incident. In the wake of the Hollywood Presbyterian ransomware attack last year, "the obscurity we've enjoyed is gone," Corman explained. "We've always been prone, we've always been prey—we just lacked predators. Once the Hollywood Presbyterian attack happened, there were a lot more sharks because they smelled blood in the water." As a result, hospitals went from being off attackers' radar to "the number-one attacked industry in less than a year," he said.

The task force's long-term target is to get the health industry to adopt the risk management strategies of NIST's Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity Framework. But that's a long way off, considering the potential costs associated and the bare-bones nature of many health providers' IT. Many healthcare delivery organizations "are target rich and resource poor, and [they] can't fathom further investment in cyber hygiene, period," said Corman.

The challenges to securing health IT identified by the task force, including some of the problems exposed by the Hollywood Presbyterian attack, are substantial:

A severe lack of security talent in the industry. As the report points out, "The majority of health delivery organizations lack full-time, qualified security personnel." Small, mid-sized, and rural health providers may not even have full-time IT staff, or they depend on a service provider and have little in the way of resources to attract and retain a skilled information security staff.

Premature and excessive connectivity. Health providers rapidly embraced networked systems, in many cases without thought to secure design and implementation. As the report states, "Over the next few years, most machinery and technology involved in patient care will connect to the Internet; however, a majority of this equipment was not originally intended to be Internet accessible, nor designed to resist cyber attacks."

In some significant ways, this is a problem that Congress helped create with the unintended consequences of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act. Passed in 2009 as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, it gave financial incentives for hospitals to rapidly deploy electronic health records and offered billions of dollars in incentives for quickly demonstrating "meaningful use" of EHRs. Combined with the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System used by Medicare and Medicaid, the HITECH Act forced many health providers to quickly adopt technology they didn't fully understand. While EHRs have likely improved patient care, they also introduced technology that care providers couldn't properly secure or support.

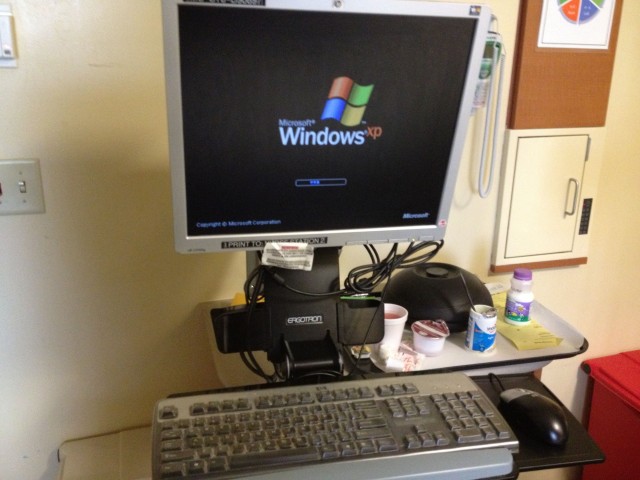

Legacy equipment running on old, unsupported, and vulnerable operating systems. Since a large number of medical systems rely on older versions of Windows—Windows 7, and in many cases, Windows XP—"there's zero learning curve for an ideological adversary," Corman said. "There's nothing new to learn." The systems were never intended to be connected to the Internet in many cases—or to any network at all. Some systems, Corman said, "have such interoperability issues—forget security issues—that they're so brittle, most hospitals will say that, even if you just do a port scan, you'll crash them—you don't even need to hack them."

On top of that, some of the legacy medical devices on hospitals' networks now are unpatchable or unsecurable, and they would have to be completely retired and replaced. The task force recommended government incentives to get rid of these devices, following a "cash for clunkers" model. But that may not be effective in luring some health organizations to get rid of them, simply because of the other costs associated with getting new hardware in. And many of the newer systems they would use to replace older ones with are still based on legacy software anyway.

A wealth of vulnerabilities, and it only takes one to disrupt patient care. The increased connectivity of health providers without proper network segmentation and other security measures exposed other systems that were never meant to touch the network—medical devices powered by embedded operating systems that may never have been patched and have 20-year lifecycles. According to the task force report, one legacy medical technology system they documented had more than 1,400 vulnerabilities on its own. And the exploitation of a single vulnerability on a single system was able to affect patient care during the Hollywood Presbyterian attack.

Furthermore, because these legacy systems are often based on older, common technologies, virtually no special set of skills is required to perform such an attack. Basic, common hacking tools could be used to gain access and wreak havoc. This is demonstrated in attacks like the one at MedStar hospitals in Maryland last March, in which an old JBoss vulnerability was exploited (likely with an open source tool) to give attackers access to the medical network's servers.

It was clear to everyone on the task force, Corman noted, that there were no technical barriers to a "sustained denial of patient care like what happened at Hollywood Presbyterian, on purpose" at virtually any healthcare facility in the United States. "I said we all make fun of security through obscurity, but what if that's all we have?" Corman recounted. "Seriously. What if that's all we have?"

Planning for "right of boom"

Given that untargeted and incidental attacks on hospitals have already happened, it seems inevitable that someone will carry out a targeted attack at some point. Corman said that increases the importance of doing disaster planning and simulations now to optimize responses, "so we can see who needs to have control—is it FEMA, the White House, DHS, HHS, the hospitals? We drill with our kids what you're supposed to do in a fire. Before we have a boom, we need to prioritize simulations, practice, and disaster planning."

Another part of planning for the post-attack scenario—or "right of boom"—is to make sure that the right supports are in place to quickly recover. "We need to make sure that we've done enough scaffolding now so that we can have a more elegant response," Corman said, "because if this looks like Deepwater Horizon, and we're on the news every night, every week, gushing into the Gulf, that's going to shatter confidence. If we have a prompt and agile response, maybe we can mitigate the harm."

reader comments

86