It may be less than a week away, but election fever isn’t exactly sweeping across the University of Derby. Among the students still milling around the campus’s lunch tables, bookshop and career advice stalls, the most pressing decision being mulled is where to watch Saturday’s Champions League final.

But if the student body isn’t obsessed with politics, the political world has certainly become obsessed with it.

At the finale of an election campaign that has seen an anticipated Tory landslide slowly crumble, shock polls have emerged suggesting a result regarded as inconceivable at the outset. They point to a surge in support for Jeremy Corbyn – the man who only stood for the Labour leadership in 2015 because his fellow leftwing MPs decided it was his turn – that could deprive Theresa May of a majority. As the Observer’s interview this weekend with the shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, demonstrates, there is palpable excitement in the Labour leadership and a new sense of ambition.

Both a YouGov projection of the result and a poll last week, putting Labour on 39% and just three points behind the Tories, pointed to such a result. However, the snapshot differed significantly from other polls, which still indicated a healthy lead for the Conservatives and a majority for May.

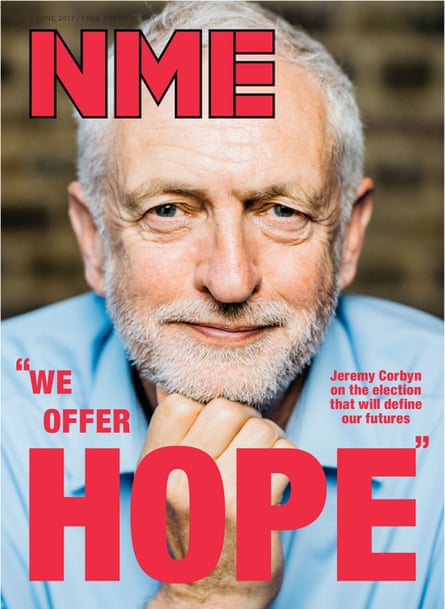

The huge divergence hinges on a key question puzzling the pollsters. Will a flock of young voters, enthused by Corbyn’s willingness to pump billions into the welfare state and abolish tuition fees, head to the polls in record numbers to back him? Will the adoring crowds that turn up to his events, the cheers he received when he pitched up at a Libertines gig, or the kudos gained from being the cover star for the NME and Kerrang! magazines translate into a new voting zeal among the under-25s?

Derby’s student body is at the centre of the election’s most contentious conundrum. The Labour candidate Chris Williamson, a vocal advocate for Corbyn and his politics, lost by just 41 votes in the Derby North seat two years ago. Just a trickle of new voters could secure him a win.

Certainly there is evidence that Corbyn has enthused some. Kyle Bolderson, 22, preparing for postgraduate studies, believes something is happening. “I voted here is 2015 and I know a lot of people who didn’t bother to vote and Labour just lost,” he said. “I don’t think that is going to happen this time. Brexit has got a lot of people to vote and they also want to oust the Tories. It is also down to Corbyn. You saw in his leadership election that he was inspiring to people. Tuition fees is part of it, but it’s much wider. It’s also just the fact that he is for the poor and downtrodden. That’s quite appealing.”

Chantelle Fallaize, 20, who has just finished a psychology and media studies degree, also believes there is significant motivation among her peers. “A lot of people are saying they will vote Labour because they are the ones trying to communicate with young people,” she said. “Jeremy Corbyn appeared at a Libertines gig. He is the one who has been pushing to talk to young voters. Corbyn is really going for it. Ed Miliband wasn’t that bad, but Jeremy Corbyn understands how to interact and get them to vote. People are motivated.”

She has been so impressed she is planning to help Williamson and his team get people out to vote on polling day. There have been a series of campaigns to ensure young people are on the electoral roll and have a vote in the first place, run by the likes of Citizens UK, RizeUp and Bite the Ballot.

If Labour is to secure a close result and prove the doubters wrong, there will have to be many more like Bolderson and Fallaize out there, signed up and ready to vote. In fact, there will have to be an army of Boldersons and Fallaizes – left-wing, politically engaged twentysomethings – committed to voting.

Speaking to others at the university, support for Labour is clearly significant among those who expressed a view. Yet just as many said they didn’t know how or whether they would vote. A whole group shook their head when asked if they would make it to the polling station.

That is why, outside the Labour leader’s office, the scepticism about the idea that its fortunes will be rescued by new and non-voters is enormous. In fact, in many cases it has spilled over into anger that the very idea of a surge is masking huge challenges in marginal seats.

“It is complete fucking nonsense,” said one Labour insider out on the campaign trail. “Polls should be banned. I haven’t met any party figure, any serious activists, any MP, who thinks we’re going to gain a single seat, never mind getting rid of the Tory majority. Where are these seats coming from? Who are these people flooding to Labour, because we are struggling to find them.”

Another said that, while things were improving, they were not picking up huge levels of new support and that finishing with 200 seats, from the current haul of 229, would be a huge success.

A third said: “In 2015 the big realignment was the loss of Scotland as a result of the independence referendum. This realignment is the EU referendum, with the white working class up for grabs for the Tories. They are sick of the lack of patriotism, they just want Brexit to happen. That is what we are seeing on the ground.

“We’re not reversing in-work welfare cuts for the working poor, but we are abolishing tuition fees. Our retail offer is aimed at students, and we’re just hoping the working poor will stay loyal to us.”

Labour party sources said that some senior figures in the leadership team did believe the polls, with some talking about a last-minute switch to target Tory-held marginals.

Pollsters and academics with concerns point out that we have been here before. Cleggmania collapsed. Milifandom flopped. Even though huge numbers of young people signed up to vote in the EU referendum, some ultimately did not cast their ballot.

James Morris, who was Ed Miliband’s pollster in 2015, is among those who doubt the huge surge. “When we did a post-election poll last time, we found that non-voters were only marginally more pro-Labour than voters,” he said. “The idea that there is a sudden emergence of a highly engaged group of under-25-year-olds who have all adopted very leftwing views does not ring true at all. If you think that hasn’t happened, then you can’t really trust the closest polls. Corbyn’s greatest achievement is lowering expectations. He appears to be persuading people that being 15 points behind, and losing both national vote share and seats, would be a triumph.”

The potential army of young voters may also be in the wrong places. Ian Warren, a polling expert who worked with Labour in 2015, has calculated that there are only 75 seats where 18-24s outnumber over-65s – and Labour already holds 57 of them, with an average majority of 14,247 votes. It means the voters aren’t well placed to help Labour make gains.

Stephen Fisher, the respected election modeller at Oxford University, said that the close polls assuming big support for Corbyn among the young should be “taken seriously” but not relied upon.

“The qualitative evidence shadows some support for that idea. Corbyn had huge crowds cheering him in Cambridge at the leader debates, mostly young people,” he said.

“It is also not hard to find people who think he is authentic and a conviction politician. They weren’t saying that about Miliband two years ago, so there is a ring of plausibility to the idea.

“The main concern is that it is really only one pollster who is finding this. Other polls are all still showing big differences, with young people much less likely to vote and not appreciably different to how they behaved in 2015. There is no clear answer here.

“Two weeks ago we were all worrying that an average Tory 18-point lead was too big, now we’re worried in case the lead is way too small. The truth is probably somewhere in between, but we need to take seriously both ends of the scale.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion