In the 20 years since Hong Kong returned to Chinese rule, the city has been able to count the numerous economic blessings it receives from being on the doorstep of the world’s second-largest economy. Yet many young people feel they haven’t reaped the benefits of those blessings, and that closer integration with China has actually made them worse off.

On the one hand, the semi-autonomous region has played a pivotal role in China’s financial liberalization, serving as a gateway for foreign investors seeking access to China’s markets and creating huge business opportunities for financial services companies. The tourism and retail sectors have thrived on the millions of Chinese visitors who come to Hong Kong to buy up luxury items and drugstore essentials alike, and maybe take in Disneyland as well. GDP growth hit 4.3% earlier this year.

Yet it would take someone like Tyrus Ng, a 29-year-old entrepreneur, over 34 years to pay for a single parking spot recently bought by a Hong Kong tycoon for well over half a million US dollars.

“I don’t want to work for others. Salaries are low. One person has to do the job of two people,” says Ng, who started his own business selling socks he designed after feeling disillusioned as a retail worker. He now makes HK$12,000 (US$1,540) to HK$13,000 a month, similar to what he earned before, but says he prefers the freedom and responsibility of owning his own business. “There is no happiness in work in Hong Kong.”

Even though Hong Kong is basically in a state of full employment, real wages for those aged between 20 to 24 have risen just 3.4% since 2004, according to government data. The median monthly wage for someone up to age 24 is HK$11,900. Graduate starting salaries have actually fallen since 1993.

Out of reach

Much of the anger felt by Hong Kong’s youth centers around real estate. Renting a home—let alone buying a property—is out of reach for most young people. A flat as tiny as 200 square feet (18.6 square meters) typically costs at least HK$10,000 a month. It would take a Hong Konger on average 18 years of saving 100% of his or her earnings in order to buy a home, according to research firm Demographia, compared to 11-and-a-half years in 2010.

Prices are kept high in part by billionaires, including mainland Chinese ones, buying up luxury homes, as well as a currency that is pegged to the US dollar, meaning local policymakers cannot set their own interest rates to curb property prices. Most young people live at home with their families in tight quarters, which makes it difficult, as one young former lawmaker remarked, for couples to have sex.

High retail and commercial rents also stymie the entrepreneurial ambition of Hong Kong’s young. Entire neighborhoods have catered to Chinese tourists, pushing out small businesses and driving rents in some parts of Hong Kong to the highest in the world. But the retail sector also shows the double-edged sword of close ties with the mainland: Hong Kong’s growth sank last year when fewer Chinese visited.

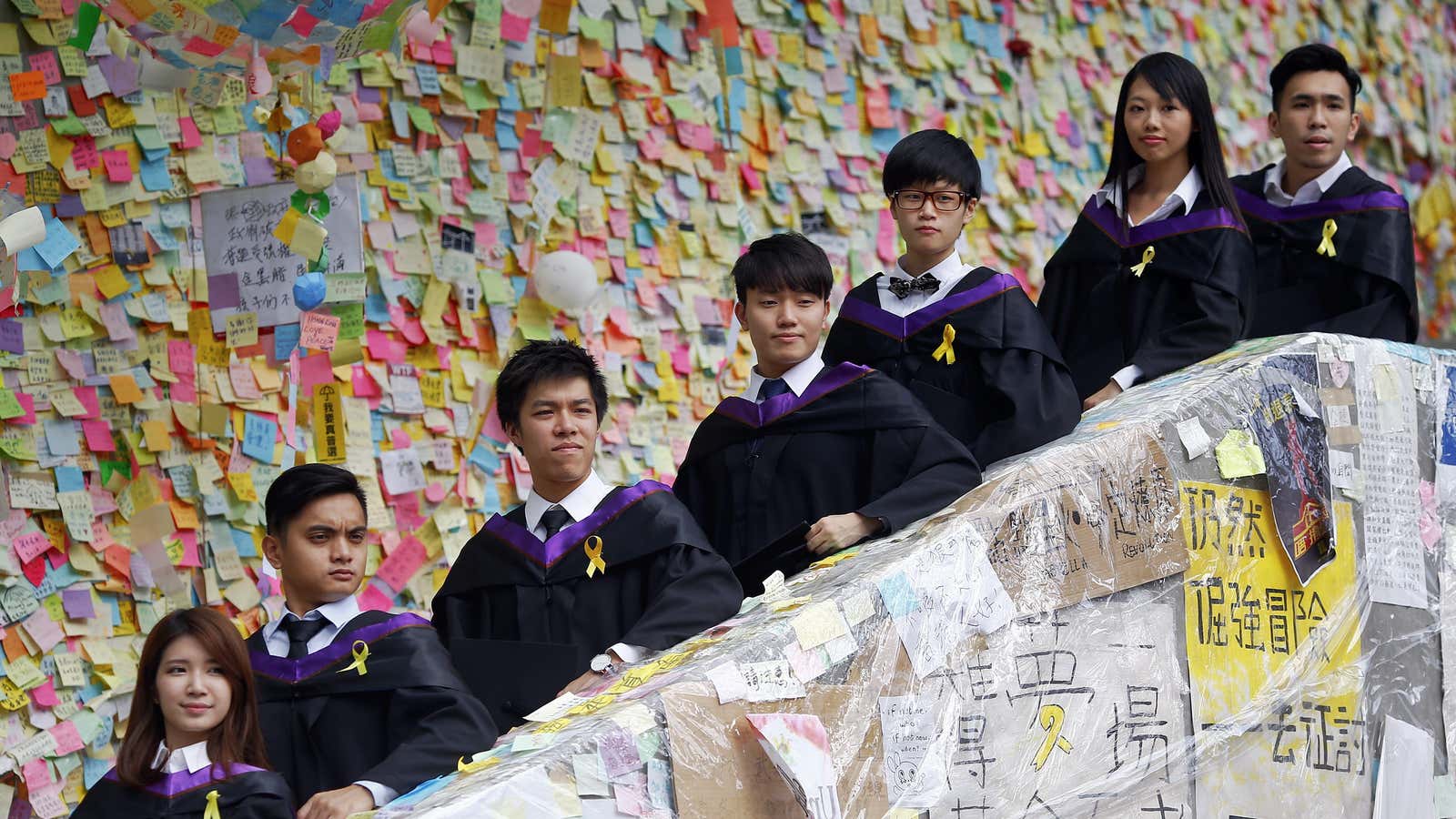

Underpinning the resentment is the feeling that Hong Kong’s government is not accountable to its people, least of all to its young. This discontent was a chief catalyst behind the 2014 Umbrella Movement protests, which saw tens of thousands of people, mostly youth, camped out on major Hong Kong streets for almost three months.

The protests were sparked by Beijing’s decision that Hong Kong will not be given full universal suffrage to elect its leader in 2017. That was a clear signal to young people that they would have little agency over their political and economic futures. This year, fewer than 1,200 of the city’s 7 million people got to vote for Hong Kong’s new leader—among those who could were Hong Kong’s richest man and two of his sons.

Since the protests, Hong Kong’s young have been a thorn in Beijing’s side, even as local leaders seek to foster a more patriotic, docile population. Some youth are even advocating the radical option of independence for Hong Kong. Two popularly elected lawmakers were last year forced out of Hong Kong’s legislature partly for expressing such sentiments.

“Engaging young people”

The newly elected chief executive, Carrie Lam, takes office on July 1; she was one of the bureaucrats who negotiated with student leaders in a televised debate during the Umbrella Movement protests. Seen as a less divisive and despised figure than the current leader, Leung Chun-ying, she’s pledged to ameliorate Hong Kong’s economic and political divides. In a recent interview with the BBC, she acknowledged that the government needs to do more in “engaging young people.”

Lam now faces the unenviable goal of pleasing her Beijing bosses while trying to restore trust among the Hong Kong public. But some of Hong Kong’s problems are so deep-seated and intractable that in practice, there is little Lam can do about them. One example is the continuing stranglehold of Hong Kong’s richest families over the city’s economy—though spare a thought for these clans, too as even local tycoons are feeling the heat from their mainland Chinese counterparts.

Hong Kong’s long-held role as the financial gateway to China is by no means a given, particularly as China becomes more integrated (paywall) into the global financial system. China continues to press ahead with plans to build its own financial hubs to rival Hong Kong, such as Shanghai, though in reality that still remains a distant dream. In other areas, Hong Kong is already ceding ground to mainland China. The city’s prominence in global trade, for example, is weakening as less cargo (paywall) passes through its port in favor of newer terminals on the mainland. Meanwhile, global tech companies such as Airbnb and Google are choosing to base their regional operations in Singapore instead of Hong Kong.

Young people themselves have indicated they may be the city’s biggest export: In a Chinese University of Hong Kong survey conducted last September, 57% of people aged 18 to 30 said they want to emigrate. Lam will need a new formula for growth to win them over. In the meantime, Hong Kong risks alienating the very people who would sculpt the city’s future.

Read Quartz’s complete series on the 20th anniversary of the Hong Kong handover.