Rice Was First Grown At Least 9,400 Years Ago

Archaeologists have unearthed bits of rice from when it was first domesticated in China.

Around 10,000 years ago, as the Pleistocene gave way to our current geological epoch, a group of hunter-gathers near China’s Yangtze River began changing their way of life. They started to grow rice.

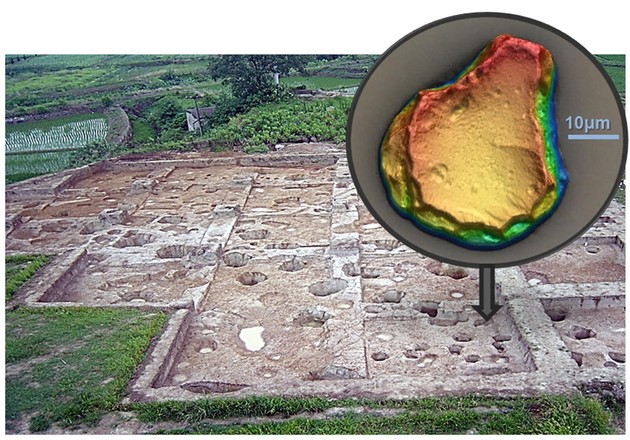

Remarkably, archaeologists have now unearthed bits of this rice at a site called Shangshan. The grains, of course, were eaten long ago and the plant stalks have long been rotten, but one tiny part of rice remains even thousands of years later: phytoliths, or hard, microscopic pieces of silica made by plant cells for self-defense. Rice leaves have fan-shaped phytoliths that don't burn, digest, or decompose. It’s specific patterns on these phytoliths that suggest people in Shangshan were not just gathering rice, but actually cultivating it 10,000 years ago—a transition that would profoundly shift the human diet to the point where half of the world relies on the staple crop today.

Chinese archaeologists began excavating Shangshan in the early 2000s. They quickly found evidence of a rice-dependent diet: rice husks buried in pottery shards and stone tools that looked like they were used for milling. But far more abundant than artifacts are phytoliths, which are ubiquitous, if microscopic, in soil. Less than a tenth of an ounce of soil might yield thousands of phytoliths, says Dolores Piperno, a phytolith expert at the Smithsonian who was not involved in the study.

So the Chinese team went through the tedious process of sifting the phytoliths from dirt, washing and sieving and heating until they ended up with a white powder of pure phytolith. They then used carbon-14 dating to pinpoint the age of phytoliths found at different depths in the excavation. To prove the reliability of dating phytoliths, they compared the ages to that of other material, like seeds and charcoal, found at the same depth “It’s robust and they very carefully compared phytolith dating side by side,” says Piperno. The oldest material was as old as 9,400 years.

Then they peered at the phytoliths under the microscope. The rice that the people cultivated at Shangshan 9,400 years ago was not like the rice we eat today. The grains were likely small and thin. They scattered easily—as seeds trying to disperse themselves are wont to do. Just as 10,000 years of domestication has transformed rice into fat, starchy grains that cling to the stalks for easy harvest, they have transformed the phytoliths, too. The team turned their attention to surface patterns on the phytolith which are shaped like fish scales.

Phytoliths in modern rice have more than nine fish-scale decorations. The ancient phytoliths in Shangshan were a mix of different numbers of fish-scale decorations—as they got younger, the proportion with more than nine increased and more like modern rice. This is evidence of rice’s gradual domestication, a process that is “long and slow,” says Jianping Zhang, a geologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences who was part of the study. Wild rice didn’t become modern rice overnight.

But what exactly do fish-scale decorations and domestication of rice have to do with one another? These phytoliths are in leaf cells, which curl up to hold water when dry. “Wild rice usually grows in swampy conditions,” says Zhang, so they get plenty of water. “Domesticated rice leaves are erect and distant from water, and so the leaves need to curl repeatedly to hold water.” The curling creates more fish-scale decorations. These microscopic fish-scale patterns tell the story of a rice plant that lived some 10,000 years ago.

The phytoliths add to accumulating evidence that Shangshan is the first place where rice has been cultivated—at least that has been found. But there is some controversy over whether it’s the only time rice was domesticated. Genetic evidence has pointed to one, two, maybe even three domestications over time to explain the different varieties of rice in Southeast Asia. The story of rice’s domestication may have begun in Shangshan, but it’s since continued all over the continent and all over the world.