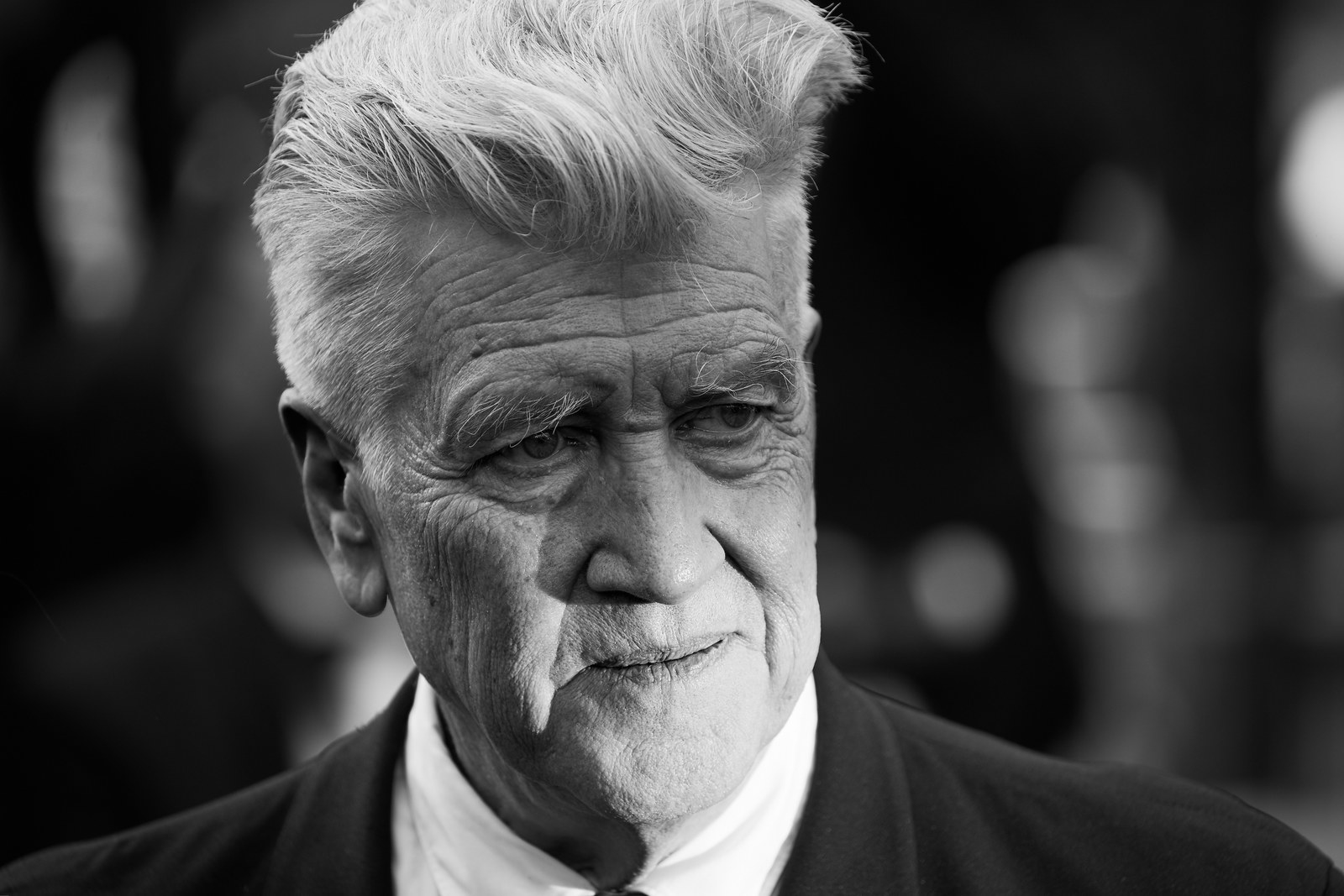

When it comes to Twin Peaks, it might make a perverse kind of sense (and if we’re talking David Lynch, that’s the main kind) to begin not by attempting to schematize what the new, 25-years-later season of Twin Peaks is and is not, or rehashing the by-now-familiar details of its 1991 cancellation, gradual enshrinement in popular culture, and premium cable resurrection, or even to confront head-on the famously inscrutable, famously baroque imagination of its director, but by positing instead a simple question. Namely, if you take a certain stylized television show, with memorable characters and a central mystery, then deviate wildly from that established style, reducing those memorable characters to cameos, ignoring the established mythology, and otherwise opting to do whatever you’d like instead of what your audience of two decades is eagerly awaiting, is it the same show or something entirely different?

The question is worth asking because, as of the first four episodes of the relaunch, Showtime is airing something that is called Twin Peaks and which certainly borrows a handful of its regular cast members and locations from the early ’90s phenomenon of the same name, which was frequently credited with jump-starting prestige television in the US, but that is just about where the resemblance ends. This Twin Peaks is a place where beings of Francis Bacon translucency materialize inside glass boxes, bodies emerge from electrical sockets wholesale after plummeting through an industrial abyss, and exposition is allocated to giants, ghosts, and trees. The plot, again conceived with co-creator Mark Frost, is just barely narrative, concerning two iterations of Special Agent Dale Cooper (Lynch lucky charm Kyle MacLachlan), the disembodied one who must escape from the Black Lodge, where he was trapped at the conclusion of Season 2, and an imposter, carrying out various nefarious deeds in a hick-noir nowheresville of sinister motels and gruesome shotgun shacks.

These strands are bookended by brief check-ins with the denizens of Twin Peaks, who frankly don’t appear to have been up to much in the long interim between seasons. The show delights in long takes, ludicrously empty scenes at the sheriff’s office — drawn-out discussion of chocolate bunnies, slapstick gags about cell phone reception, a goofy appearance by Michael Cera as a Brando-esque biker whose “dharma is the road” that manages to be the strangest thing in a show that regularly features psychic vampires — and diegetic musical numbers by the likes of Chromatics and Au Revoir Simone. The pace is so slow, the tension between scenes so slack, that it is almost anti-entertainment. If you’ve ever seen a film by the droll Swedish director Roy Andersson, you might have some idea where Lynch is coming from. But otherwise, the prevailing feeling is probably that Showtime subscribers have been tricked into watching video art.

None of this is reminiscent of the chirpy coffee-and-cherry-pies Twin Peaks of consensual memory. When familiar faces do appear, they are fascinatingly aged — and, in the touching case of Catherine E. Coulson, who played the Log Lady mere days away from death, a rare experience for TV and a reminder that time has passed in the real world too. To state the appallingly obvious, the America on display in these episodes is not the one we left 25 years ago. And in this present, David Lynch, with his rural grotesquerie, fondness for plasticity, and contention that ugliness pushed to its limit achieves beauty, suddenly reads as the one thing nobody has ever accused him of being: a realist.

Today, David Lynch suddenly reads as the one thing nobody ever accused him of being: a realist.

It can be hard to remember (or would be, if we weren’t constantly being reminded) just what a wasteland television was when the Twin Peaks pilot episode aired on ABC just four months into the 1990s. Small towns still meant the corn muffin goodness of Green Acres or The Andy Griffith Show and not because life was actually simpler, or any less scabbed over with iniquity and painful secrets, but because television functioned almost exclusively as a normalizing force. During the day people on television went to regular jobs and at night they had regular families. We measured ourselves against that pervasive normality — never mind that it was so artificially circumscribed that you had to be reminded when to laugh. Situation comedies were hokey simulacrum, and soap operas were, well, operas, not intended to simulate the ins and outs of existence as much as promote it to dramatic grandeur.

The small-town soap opera of Twin Peaks had the same basic grammar as other shows, at least initially, but suddenly you could see around the corners, past the soft-focus surfaces, and catch the reflective glint of something true. Laura Palmer, a drug-addicted homecoming queen with a secret life, had endlessly more in common with the average teenager than the fresh-faced cast of Saved by the Bell. It wasn’t just that the show was willing to depict grief. Take the the still-jarring scene in the pilot when we watch virtually every citizen receive the news of Palmer’s death individually (best friend Donna — played by Lara Flynn Boyle — bursting with tears at the empty desk in homeroom, her mother’s wishful rationalizations at discovering her daughter didn’t come home the night before giving way to the realization that she never will). It was that the show specialized in a sadness all the more realistic for being paired with absurdity (Leland Palmer — played by Ray Wise — manically breaking into song while clutching a framed picture of his daughter) and dreams (where we all know Agent Cooper receives his intel).

But more than anything, Twin Peaks confronted incest. Sure, the show ascribed Laura’s long-term abuse to the otherworldly spirit-possessor BOB (causing the pain and suffering that manifests in Twin Peaks mythology as creamed corn!), but we knew what we were looking at — a daughter’s efforts to hide her ongoing rape at the hands of her father from everyone, including herself — and wondered how it could have taken us so long to recognize the signs: the mother’s deep repression, the powerless temerity of her friends, the possessiveness with which the male characters, all of whom lay some claim to her physicality, mourn for “our Laura.” (This might also be why the film prequel, Fire Walk with Me, which tackled these concerns even more explicitly, was maligned everywhere but Japan.) Far from celebrating the single-stoplight American "anytown," Lynch held small-town mentality responsible for every facet of Laura’s fate up to and including her murder. At her funeral, erstwhile bad boy Bobby Briggs asks the town, and by extension the audience, “You want to know who killed Laura Palmer? You did! We all did.” (Another scene, in which Laura’s psychiatrist suggests “maybe she allowed herself to be killed” hasn’t aged quite so well.)

At the time, exposing the festering illness behind rural bonhomie was a revelation. It is less so now. We may have caught up with Lynch, seeing the American hinterland less and less as pastoral idyll. It’s no secret that the county’s liberal-leaning metropolises are at war with its ruddy, God-fearing backwoods — but one thing that gets left out when discussing the blue-collar breadbasket is just how weird life gets in the great wide open. The random craziness that so offended Roger Ebert in Lynch’s 1986 classic Blue Velvet, the way it transmits and infects only to erupt into outbursts of startling randomness, is something every country-born person I’ve ever watched it with recognizes immediately. Lynch’s violence exudes from an indeterminate source, to no particular profit. None of your citified mobsters here.

Speaking as someone who grew up in a town of 20,000 (but felt much smaller), there are things which, looking back, I absolutely cannot account for because they actually seem to occupy a different reality. The unspeakable: That’s the territory I see Lynch harvesting onscreen (presumably via transcendental deep dives into his heavily caffeinated bardo), though it’s more commonplace now that we’ve given up on bucolic innocence. Still, Lynch succeeded in bringing verisimilitude to the inexplicable and showed the agreed-upon, learned normality of the everyday for the myth it was. Don’t be fooled by the backward-talking dwarves or log ladies — Twin Peaks was never truly surreal; it was simply a novel, reach-around approach to realism. The task of the new Twin Peaks is not to recapture or reboot that legacy — Lynch wouldn’t be caught dead — but to reckon with it intelligently.

Faced with certain mystifying or hallucinatory moments (say, the dancing-girl-as-semaphore in Fire Walk with Me or, in the new series, the tree that communicates via a deflated dollop of ectoplasm in lieu of a face) it’s become habitual to shrug and say “Well, that’s David Lynch!” as though conceding that we’ve unanimously decided to give this one weirdo a blank check for peculiarity. What that assumption overlooks is how disciplined an artist Lynch really is. Surrealism is easy; if you’ve seen an elephant and a giraffe, you can picture an elephant with the legs of a giraffe. The challenge is painting a convincing elephant, which is why Lynch’s best work needs the prosaic sheen of stock Americana. David Foster Wallace brilliantly defined "Lynchian" as “a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter.” Ted Bundy isn’t Lynchian, but Dahmer, with his victim’s extremities piled in the vegetable crisper, fits the bill. (This is Wallace’s example, though the binary is infinitely modular: O.J. versus Lorena Bobbitt, Donahue versus Jerry Springer, Mickey Mouse versus Betty Boop.)

Think of Lynch’s most un-Lynchian films like The Straight Story, the G-rated journey of Richard Farnsworth riding his tractor from Iowa to Wisconsin in order to reconcile with Harry Dean Stanton. Better yet, think of the Lynch-produced Interview Project, the series of documentary shorts in which off-the-beaten-track locals give accounts of themselves: There’s a self-described "buccaneer" on the Mississippi, a miniature-trolley builder named Mr. Siebert (“Of course there are very few trolley cars anymore, but I still build them like they were in those days”), and a 77-year-old West Virginia man, discovered by the crew on his front porch, who claims never to have had dreams beyond finishing high school but who “might have had some nightmares some nights.” What could be more normal? But Lynch seems to dare us to stare deep into the "ah-shucks" sensibility even as he flatters it, to perceive the throbbing freakazoid within.

The counterpoint to "Down-Home Lynch" is "Spindly Nightmare Lynch," the somnambulist auteur behind his most unrestrained films such as Eraserhead and Inland Empire, and early shorts like The Grandmother. These happen to be the works that most resemble his often undervalued paintings and sculptures, scratchy blobscapes with titles like “Dr. Howl’s Philosophy” and “Nothing Is Making Any Sense For Instance Why Is That Boy Bleeding From the Mouth.” (The talking tree from the new series looks cribbed from this aesthetic.)

But most Lynch flirts between the two poles and the tension between them is what keeps us coming back and how we measure the success of a given film. Lost Highway, for example, is too on the nose or frivolous, while Mulholland Drive and Wild at Heart strike just the right balance between absurdity and obscurity. The old Twin Peaks tended toward the former, minimizing the supernatural incursions into human drama; the new one, however, veers so far into oblivion that parts of it seem designed to rankle even the most devout disciples.

If the new show denies us the cozy wit and security of the old show, if it is in fact crazy, nasty, and otherwise “off” for much of its runtime — well, we feel crazy, nasty, and off a majority of the time.

One thing that’s true is that no one could have seen this coming. In Episode 4, an amnesiac Cooper wins jackpot after jackpot in an interminable casino sequence before being driven to a home and a wife he doesn’t recognize (Naomi Watts — just one of many A-list actors anomalously cast in bit parts). What follows is a Freaky Friday scenario more fitting of a Nickelodeon cartoon: Coop wears a tie on his head! He doesn’t know that coffee is hot! He clutches his groin when he needs to pee! Meanwhile, the contents of a trunk confiscated by the feds could serve as a shorthand for Lynch’s entire oeuvre: “Cocaine. Machine gun. Dog leg.”

Another sequence takes place in South Dakota where Matthew Lillard from Scream is seemingly framed for a grisly murder, yet we spend as much time watching the police deal with the victim’s bungling neighbor as we do in Lillard’s cell — then the camera pans over to a weird lumberjack who dissolves before we can register what we’re looking at, aaaaand we’re out. Case…closed? In one of the Black Lodge scenes, the generally benevolent one-armed man, MIKE (Al Strobel), tells a new character just before his face flies off like a deflated balloon animal and he transforms into a golden bead, that “Someone manufactured you for a purpose.” But did they? What purpose? Is there any point to this tale of two Coops? And are we ever going to follow up with the freestanding mini-subplots like Ben and Jerry Horne’s edible marijuana business, Lawrence Jacoby’s weird shovel-sculpture, or James Hurley, who so far has literally just walked into a bar and waved?

Don’t ask me. I want to get Cooper out of the Black Lodge and back into his body as much as the next guy, but I’m mostly here for the lampshades and creamed corn — the trademark, otherwise innocuous set dressings fetishized by Lynch’s camera until they pulse with energy, mystery, and an uncanny recognition out of dreams. This same esoteric/banal crosshatch extends to the dialogue. Before regional bureau chief Gordon Cole (David Lynch himself, stealing a name from Sunset Boulevard) meets with David Duchovny’s Denise Bryson, there’s a lengthy interlude with some guy named Bill. Cole asks after his wife, Martha, and whether she “ever fixed that thing with Paul.” Bill nods, raises his eyebrows and replies, “Paul is now in the North Pole.” Cole’s rejoinder is classic: “Well, there you go!” Normally, this would be the cue for an audience to ask “Who is Paul," “What was the nature of his business with Bill’s wife,” and “What on earth is he doing in the North Pole,” but I wouldn’t hold my breath.

Still, it leaves no question that Bill is possessed of an interiority apart from the show’s narrative designs on him. These eccentric, throwaway touches make us love Lynch — touches that are at once stagy and extremely accurate with regard to real life’s barrage of inexplicables, the very thing fiction tends to leave out lest it clutter the field with false signals as to what’s important. In Twin Peaks, however, everything seems important, so even in the clumsiest or most extraneous dialogue Lynch seems to be saying “This is you! This is what you sound like!” Which might go some way toward explaining why the Twin Peaks we’re getting with these 18 episodes — obviously just an 18-hour movie chopped up randomly — is the Twin Peaks we deserve.

A friend of mine told me after the premiere that watching the new season was nearly as traumatic as the presidential election. The old mild-mannered president was gone and, in his place, an agent of chaos in whose shadow the once familiar country felt unrecognizable. Nothing that lived in the imagination appeared to fit the circumstance, and there was the feeling, he said, that the pre-Trump world was stuck in the Black Lodge, leaving us in a free fall through a dark, unpleasant, implacable present. Of course, Lynch couldn’t have known how well his difficult new Peaks would suit an off-kilter country struggling to remember what it had once seemed to be. But much of the press material released prior to the new season had underscored, somewhat self-consciously, that Twin Peaks was Lynch’s statement on the American dream and his vision of what is becoming of its values. If the new show denies us the cozy wit and security of the old show, if it is in fact crazy, nasty, and otherwise “off” for much of its runtime — well, we feel crazy, nasty, and off a majority of the time. It makes perfect sense that pie, coffee, and cigarettes (Lynch is an unreconstructed smoker) are cold comfort when it becomes harder every day to do as Lynch-as-Cole suggests and “Fix your hearts or die.”

For sheer immediacy, there’s very little contemporary art that comes close to the kind of lucidity that the show communicates even at its most fractured. And yet the best scene so far is a callback: Just as we’ve discovered, in a funny reveal, that the sleepy Twin Peaks sheriff’s department is actually outfitted with modern dispatchers and tripled its on-call staff, Bobby Briggs — the quintessential no-goodnik now an officer of the law — walks in on the old homecoming photo of Laura Palmer that’s been pulled from an evidence bin. The camera zooms in on actor Dana Ashbrook’s face as he tenses and tears up, while, right on cue, the first unforgettable strands of Angelo Badalamenti’s “Laura’s Theme” swell in tune to his trauma. Suddenly we’re back, and it feels crushing. Real magic, as Lynch knows, resides outside the conventions of storytelling, a mystery to which there are no answers, only more questions in a world of blue. ●