Hard Hit, So What? Robbie Ray Doesn’t Care

Robbie Ray. There’s so much we’ve said about the guy. He’s been tantalizing. He’s been frustrating. He’s been monstrous. He’s been dismal. For everything you had nice to say about him entering the season, there was a big caveat attached. “He’s got big velocity, but struggles to put guys away.” “That breaking ball looked good, but did you see the last five?” “He didn’t allow any runners past second base, but he lasted just five innings.” If I had a dollar for every time I uttered one of these phrases, or something thereabouts, well, I’d have a lot more dollars.

But after Ray’s complete game shutout of the Pirates this week and with his 23.2 scoreless innings streak still in tact, we’re using fewer “buts” when talking about Ray. They’re not cautioned phrases anymore — they’re statements. He’s been simply dominant in almost every facet of the game. He’s ninth in baseball (among pitchers) in fWAR, sixth in K/9, 15th in FIP, seventh in swinging strike rate and fifth in contact rate. Think about that: the guy who pitched well at times last season but ended the year with an ERA approaching five has quickly become one of the premier arms in the National League.

You’ve maybe asked yourself “how did he do it?” but you mostly know the answer. He throws hard from the left side. The fastball has movement. He locates it better at some times than others, but it’s an effective pitch. His slider and curveball have slowly started to differentiate themselves, something that Eno Sarris of FanGraphs talked to Ray about. He’s effectively stopped throwing the changeup that’s given him problems in the past (something Patrick Corbin might consider going forward). It’s more of the good, less of the bad. Sounds easy enough, right? It’s easy to forget that he’s just 25 and is still improving, growing his knowledge of hitters and how to pitch, refining his craft. Add some experience and refinement to a good arsenal and good thing can happen. That’s why you trade for young pitchers, I suppose.

Search the leaderboards for pitchers and you’re sure to see Robbie Ray featured in a positive light, except for one thing: he’s allowed more hard-hit balls, on a rate basis, than any other qualified starting pitcher.

I found this a few days ago and had to do a double take. How does a guy sporting such incredible numbers lead the league in hard-hit rate? Hard hit balls are great for hitters, but terrible for pitchers. Hard hits do the most damage, so shouldn’t Robbie Ray be getting penalized deeply for these crushed baseballs? It would only stand to reason that Ray would pay the price, but thus far, he really hasn’t.

The first response is to chalk it up as luck. Maybe all of those hard-hit balls were headed straight for an infielder or outfielder and those balls are being converted to outs at an unreasonable rate. Without going through every hard-hit baseball this season for every pitcher in the game, I can’t say for sure if he’s having some kind of weird luck on hard-hit balls becoming outs rather than hits as compared to his peers. Maybe there’s some luck here, but I just can’t say.

But let’s think of it differently. We know that hard-hit rate is a simple equation. It’s the number of balls that are hit hard divided by the total number of balls in play. What does Robbie Ray excel at? Keeping the ball from being put into play. As per usual, he’s near the top of the charts in strikeout rate. None of those balls are put into play. He’s 24th in terms of total batters faced, thanks to his longer-than-usual starts, but he’s walked the sixth-most batters among qualified starters. Mix in a couple of hit batters and, well, even though he’s faced a ton of guys, a lot of them are never putting the ball into play, reducing the size of the denominator in our hard-hit rate equation.

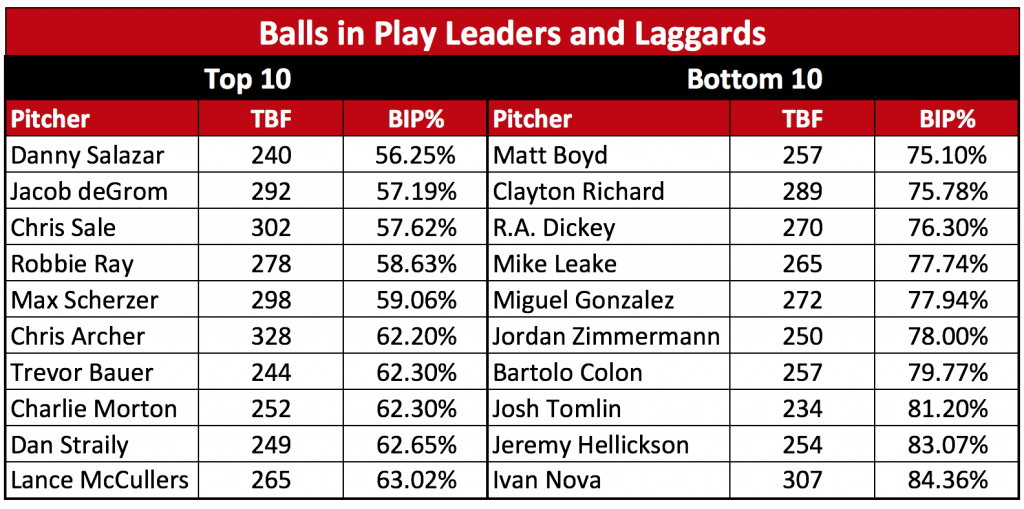

Take a look at the disparity between the top ten pitchers at keeping the ball out of play and the top ten pitchers allowing balls in play. It’s a wide gap.

Only Danny Salazar, Jacob deGrom and Chris Sale have been more effective than Robbie Ray at keeping the ball for ever entering the field of play. Being in this kind of company, including Max Scherzer and Chris Archer, is certainly a good sign. Ray has struck out over 30% of the batters he’s faced and he’s simply collecting the outs before opposing teams even have a chance to roll the dice on the ball falling in for a hit. That’s helping him tremendously as it’s a sort of boom-or-bust profile here. When guys are hitting him, they’re hitting him well, but they’re just not hitting him frequently enough to make a huge difference. Even when someone racks up a double, it’s no guarantee the next batter won’t simply strike out. That’s helping him post a left-on-base rate of nearly 80%, placing him in the top 20% in that category among all qualified starters.

This is why strikeouts are so critical. The old adage of the strikeout being the “pitcher’s best friend” is so apt. Even if you yield a hit, you can still bail yourself out with a strikeout, or in Ray’s case, a couple of strikeouts. True, Ray’s had better command, ditched the changeup and is throwing more curves, but that all equates to more strikeouts. It’s not that complicated with Robbie Ray — he lives and dies by the strikeouts.

The hard-hit balls are yet to impose their will on the young lefty. He’s likely been a bit lucky in terms of sequencing, but being able to bear down and get the K’s when he needs them has separated Ray from the pack. Can he keep walking that tightrope? It’s hard to say. The league is yet to make any kind of significant adjustment to him and he’s cruising along nicely for now. His raw stuff can be overpowering and that’s certainly encouraging. We’ve seen pitchers try to manage batted balls at Chase Field in the past with precarious results. Robbie Ray has forged a new path, one that avoids the uncertainty of balls put in play by just sending batters back to the dugout. How it holds it up over time will have a big impact on the D-backs’ run towards the postseason.

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Old friend alert https://t.co/6X2Su6PKrf, 14 hours ago

Old friend alert https://t.co/6X2Su6PKrf, 14 hours ago This is going to be fun and I hope you join us! #Dbacks https://t.co/YWfD7ymupf, 15 hours ago

This is going to be fun and I hope you join us! #Dbacks https://t.co/YWfD7ymupf, 15 hours ago RT @TheRattleAZ: 🚨 LIVE VIDEO SHOW TOMORROW AT 7 PM 🚨

Join @OutfieldGrass24 and @JesseNFriedman tomorrow night at 7 PM for a… https://t.co/E9X6m7HeUV, 16 hours ago

RT @TheRattleAZ: 🚨 LIVE VIDEO SHOW TOMORROW AT 7 PM 🚨

Join @OutfieldGrass24 and @JesseNFriedman tomorrow night at 7 PM for a… https://t.co/E9X6m7HeUV, 16 hours ago Disgusting. Absolutely disgusting. https://t.co/xIPKxM4viX, 16 hours ago

Disgusting. Absolutely disgusting. https://t.co/xIPKxM4viX, 16 hours ago RT @cdgoldstein: What are minor league teams doing to make a mark on their community without a minor league season? @OutfieldGrass24… https://t.co/4Kp6mVa0eC, 17 hours ago

RT @cdgoldstein: What are minor league teams doing to make a mark on their community without a minor league season? @OutfieldGrass24… https://t.co/4Kp6mVa0eC, 17 hours ago

Powered by: Web Designers