Education

Memoirs: Learning Too Late About Our Dad’s Military Life

Piecing together family history can come about by writing one memory at a time.

Posted June 17, 2017

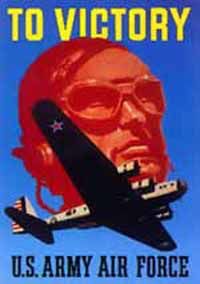

We had his dog tags, his wings, and many photos of our of dad looking both serious and smiling broadly. We knew he loved the Army and flying and today my sons have his dog tags and wings. But we were never allowed to ask about his World War II experiences. He often woke up with nightmares and I could hear him screaming. The next morning mother would say, “Don’t ask him anything." But we never understood why. He had been stationed in Florida. And if we tried to question, our mother would give us “the look.” She would then change the subject to his love of flying.

Despite his military experience, which long remained a mystery, we did know that he loved to fly. When I was 16, he told me that I had to learn to fly a plane before I could learn to drive a car. I was quite good up in the air, but I was never able to concentrate on the road long enough to become a good driver.

One day he came home and asked our mother, "Would you like to have a new car or a new plane?" She shrugged and said, "I don't know how to drive a car." And with that he told her that he had purchased a single engine Cessna 172. When he taught me to fly, we shared a memory to treasure. (Memoir Writing Bridges Past and Present, Psychology Today.)

The Memory Thief and War on our Shores

When the memory thief began hijacking his mind, he began talking of events of his past and even his military days much more openly. We began to see what troubled him -- the war at home.

It was just recently that I began researching my father’s history and came to learn that the Sunshine State had become a military training ground. It seems that enemy U-boats sank at least 24 ships off the Florida coast near Miami and Jacksonville, and special group was formed to prevent further attacks. As a pilot, our father began talking about flight operations dispatched from Florida -- the war on our shores.

I could not really understand the secrecy surrounding Florida until accounts from the New England Historical Society revealed an alleged pattern of denial about military operations along the East Coast.

As our father's dementia worsened, he went through a period of anger. He talked of being a bombardier and of the Army Air Corps. However, when he became agitated, instead of letting him talk of the negativity of his past, we focused on positive experiences in his present. And we reminded him of his glory days with Frank Sinatra. We would almost immediately see a mood change for the better.

Our Father and Frank Sinatra

Our father never lost his enthusiasm for flying. When he became a sound consultant to Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett, he traveled to Australia. There he purchased for us boomerangs and kangaroo rugs. From Japan, he brought us pearl brooches and earrings. During his time in Florida working with Frank Sinatra at the Fountainbleau, he sent home crates of fruit and coconut bars.

He was a gift-giving man whose joy with his grandchildren ranged from making paper airplanes to creating snow huts. When his talk of his Army days went from the thrill of flying to a sudden agitation, I wonder if he was looking for a way to tell us of the trauma after he came to realize that bombs hit boats and inside those boats, there were people.

Memoir Writing

In writing a memoir about growing up with Italian grandparents, I came to see all the questions we might have asked our father. Today it is too late, but perhaps in creating memoirs for our children and grandchildren, they value inquisitiveness and sharing -- even day to day experiences -- that create family richness and unity.

I saw photos of an afghan recently, quite simple and white with a colored border. Then I thought of the afghans our grandmother would make for all of her children -- squares filled with an array of vibrant and pastel colors edged in black. There was a definite individuality in each square. However, when she sewed them together, these told a story.

How do you write a memoir? It is much like making an afghan square, one piece, one memory at a time.

Copyright 2017 Rita Watson