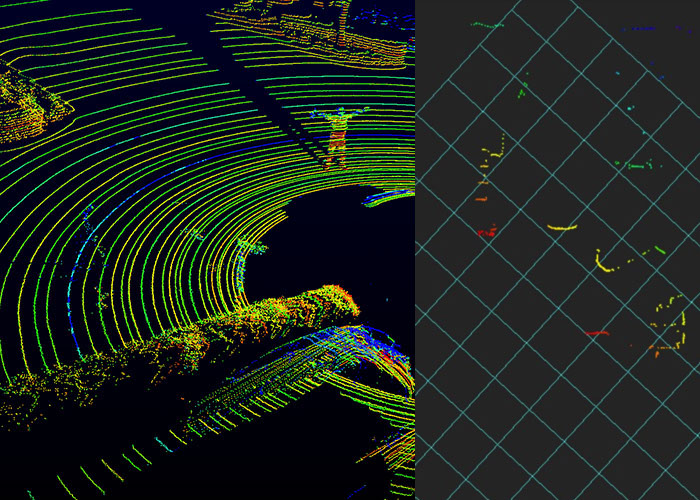

On November 3, 2007, six vehicles made history by successfully navigating a simulated urban environment—and complying with California traffic laws—without a driver behind the wheel. Five of the six were sporting a revolutionary new type of lidar sensor that had recently been introduced by an audio equipment maker called Velodyne.

A decade later, Velodyne's lidar continues to be a crucial technology for self-driving cars. Lidar costs are coming down but are still fairly expensive. Velodyne and a swarm of startups are trying to change that.

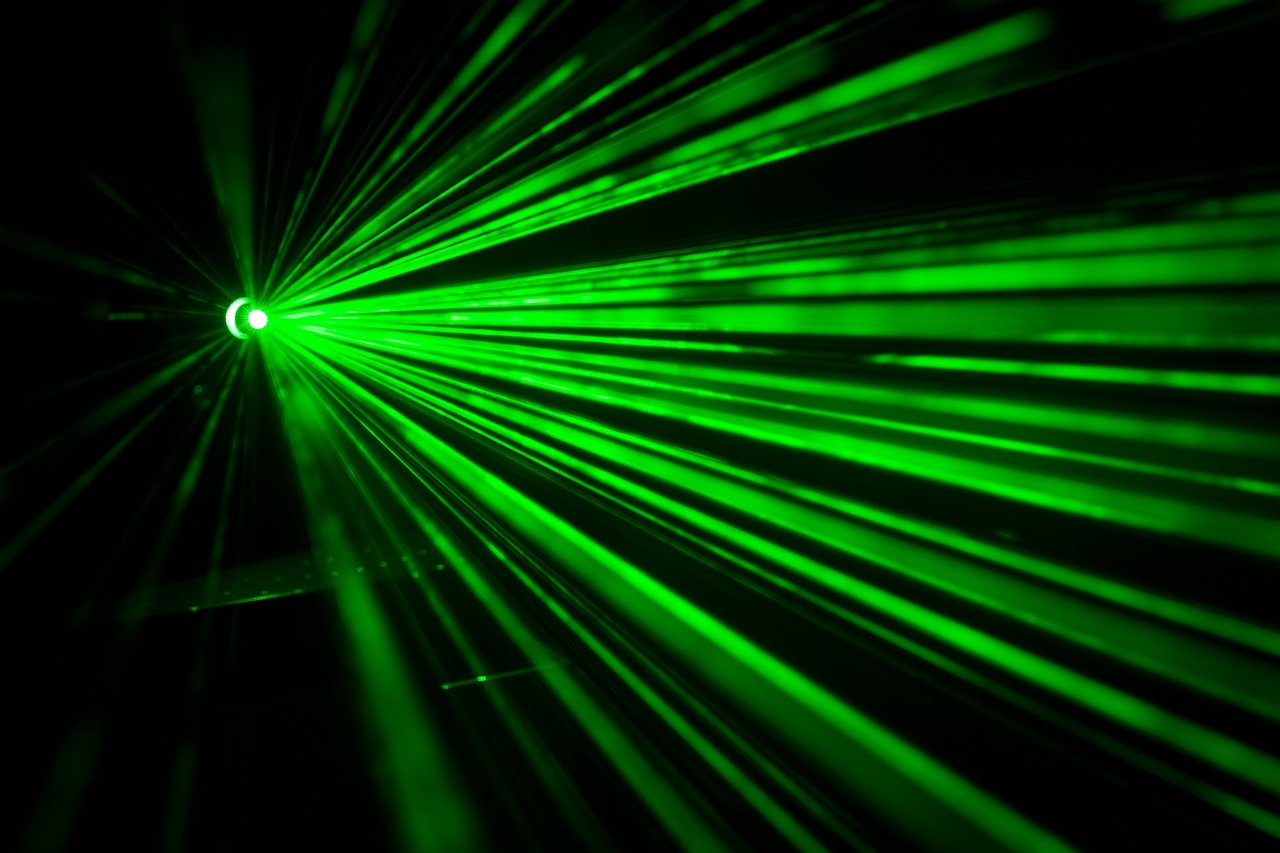

In this article, we'll take a deep dive into lidar technology. We'll explain how the technology works and the challenges technologists face as they try to build lidar sensors that meet the demanding requirements for commercial self-driving cars.

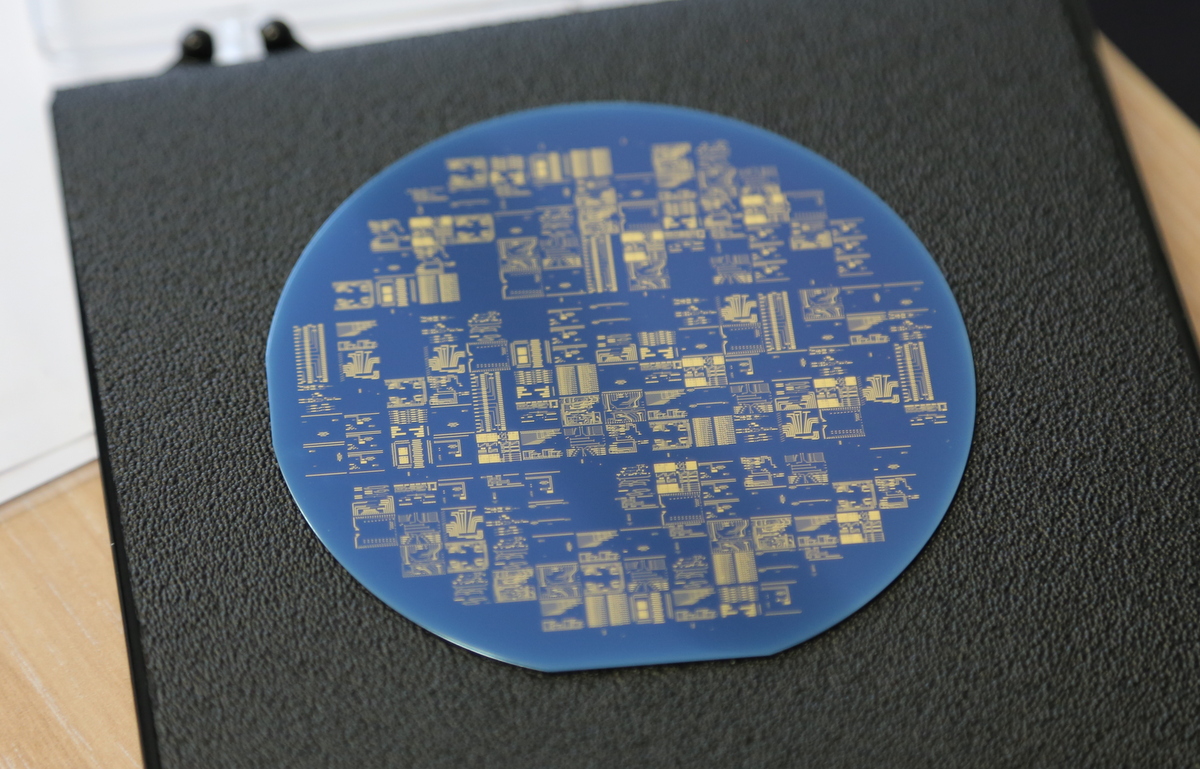

Some experts believe the key to building lidar that costs hundreds of dollars instead of thousands is to abandon Velodyne's mechanical design—where a laser physically spins around 360 degrees, several times per second—in favor of a solid-state design that has few if any moving parts. That could make the units simpler, cheaper, and much easier to mass-produce.

Nobody knows how long it will take to build cost-effective automotive-grade lidar. But all of the experts we talked to were optimistic. They pointed to the many previous generations of technology—from handheld calculators to antilock brakes—that became radically cheaper as they were manufactured at scale. Lidar appears to be on a similar trajectory, suggesting that in the long run, lidar costs won't be a barrier to mainstream adoption of self-driving cars.

An unlikely lidar pioneer

Scientists have been using laser light to measure distances since the 1960s, when a team from MIT precisely measured the distance to the moon by bouncing laser light off of it. But the story of lidar for self-driving cars starts with entrepreneur and inventor David Hall.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...