In black jacket, checked shirt and white trainers, eight-year-old D’Angelo Preston is riding his bike while his sister, Alicia, 11, gives chase. They are playing outside the Baltimore Montessori public charter school, where they would be pupils if they had the chance. “Their teachers don’t yell at them,” says Alicia matter-of-factly. “Their teachers let them do whatever they want.”

Alicia aims to be a maths teacher when she grows up; D’Angelo wants to be a professional football player. They live barely a minute’s walk from the Montessori school but, having lost an enrolment lottery, instead take a daily bus to Dallas F Nicholas elementary school, which has fewer resources. The siblings’ father, Shawn Preston, 38, a mechanic, says: “It has a good reputation and I wish more local kids could go. I tried to send Alicia but they told me it was all filled up. I was disappointed. I thought they could have got her in there somehow: we’re in the neighbourhood.”

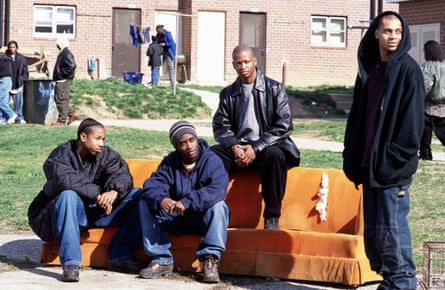

This is Greenmount West, a community striving to put distance between itself and its portrayal in one of television’s most indelible dramas: The Wire. The Montessori school building was previously home to a beleaguered government school and starred in the fourth and arguably finest season of the show. A nearby design college is still recognisable as where the “corner kids” hung out. A couple of houses near Preston’s were used during filming. Even the name D’Angelo strikes a chord as the name of a principal character in the first season.

But as the disappointment over school places illustrates, progress is painfully uneven. While some parts of Baltimore are thriving, others have gone into reverse. In 2015, the death of an African American man in police custody triggered widespread unrest, while the total murder rate of 344 was the highest per capita in the city’s history. Last year the figure was 318. In 2017 so far (up to 10 May), there have been 124 murders, outstripping Chicago and putting Baltimore on course for its bloodiest year ever.

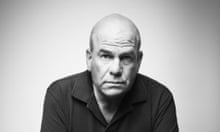

Michael Olesker, an author and former Baltimore Sun columnist, says: “It’s turf wars. It’s a battle for street corners. You’ve got 18-year-old kids killing each other. Many are from broken families. We’d like to think art can move the world but this problem is so intractable on so many levels it’s going to be with us for a long time.”

This was the world of The Wire and it is still very much intact. From June 2002 to March 2008, the epic HBO series mapped the city’s geography, society and soul, charting the never-ending street battle between cops and drug lords. It was a study of the havoc wrought by the drug war on trust between black communities and police. Its hard-boiled realism included a scene of four minutes and 40 seconds in which the dialogue between two detectives consists entirely of 31 “fucks”, four “motherfuckers” and one “fucking-A”.

The Wire never won an Emmy award or gained a mainstream audience; its acclaim rests largely with critics and fans, including Barack Obama, who named it his favourite show. It stands undiminished in the cultural pantheon. In 2015 Jonathan Bernstein wrote in the Guardian: “The temple of the US one-hour TV drama has four pillars: The Sopranos, The Wire, Mad Men and Breaking Bad, novelistic shows that indicted America for its failures but refused to condemn their complex, emotionally crippled leading men.”

When British actor, director and writer Kwame Kwei-Armah moved to Baltimore in 2011 to head the Center Stage theatre, he had not seen The Wire so he caught up via iTunes. Recently he met its creator, David Simon. “I think it’s magnificent television,” Kwei-Armah says. “I think it was voted one of the best pieces of television of the 00s and, as a document, it will be remembered. Baltimore was just a metaphor; it depicted post-industrial America.”

The Wire was intricately, unforgivingly plotted, capturing the prosaic nature of police procedural work, the brutal dynastic politics of drug kingpins and the corruption and grubby compromises of civic life. Simon has memorably said: “Our model when we started wasn’t other television shows. The standard we were looking at was Balzac’s Paris or Dickens’s London, or Tolstoy’s Moscow.”

Befitting a novel, the characters were richly realised archetypes that leapt off the screen. There was the hard-drinking maverick cop Jimmy McNulty (Dominic West), the world-weary detective Lester Freamon (Clarke Peters), the aspirational, smooth gangster Stringer Bell (Idris Elba), the quietly heroic recovering addict Bubbles (Andre Royo) and the enigmatic, gay Robin Hood figure Omar Little (Michael K Williams), whose distinctions include a facial scar, quaint turn of phrase and being Obama’s favourite character.

And in police detective Kima Greggs (Sonja Sohn), we had American TV drama’s first major portrayal of a black lesbian. In a phone interview, Sohn recalls: “I can’t say that I thought she was going to be iconic in any way, but I do think she has become so. I think she is a character I started seeing a lot more in cop shows. Who’s the tough female cop, person of colour?

“I think it’s unquestionable the impact that the show has had not only on my career but many of the principal cast. The climate was very different at that time than it is now in terms of the availability of roles for people of colour in the business. So it was quite an anomaly to see a show that would require a predominantly black cast. That in itself was unusual and something that caught the attention of us all.”

But there were detractors, she adds. “One thing that was disappointing was the city officials. They really were not pleased with the depiction of Baltimore and some of them took the storylines personally. David has always said the issues and stories of The Wire exist nationally.”

Baltimore is the Maryland city where Francis Scott Key wrote The Star Spangled Banner, Edgar Allan Poe is buried and, in 1910, the first residential racial segregation law in any US city was enacted. Once a thriving port, hundreds of thousands of small, two-storey terraced houses were built in the Victorian era as the population climbed to a million. But since the mid-20th century that number plunged and now stands at 614,664, according to the US Census Bureau – the lowest for nearly 100 years.

The series, though mostly set in the west of the city, was largely filmed in the east because the number of trees in the west made it awkward to shoot through changing seasons. Numerous houses still lie abandoned and boarded up, a few with roofs collapsed under their own weight. Pavements are cracked and smeared with graffiti. Broken bottles and other rubbish pile in gutters. On a typical Sunday afternoon, a patrol car crawls by, an officer’s tattooed arm trailing out of a window. At night, strobing police lights are alarmingly routine.

In Greenmount West, at what was “Bodie’s corner” in the series, customers have to be buzzed in to the Honey Carry Out convenience store. Inside, most of the products – M&Ms, Starburst, Skittles, earphones, Butterfinger, Almond Joy, Mounds, KitKats, Snickers, Hershey’s, Dove soap, Colgate toothpaste – are piled behind bulletproof glass like an art installation. “All transactions are final. No refund,” says a scrawled sign. Making a purchase requires placing money on a turntable, which revolves to exchange it for the product, a process reminiscent of jail.

Nearby, when we approach one resident, he explains that he returned here last year after a stretch of 24 years in prison and does not want to talk.

Yet this neighbourhood, designated an “arts and entertainment district”, is slowly but surely gentrifying. The school had shut down in 2001, before The Wire film crew moved in. The building was vandalised, had asbestos and copper pipes removed and was used as a homeless shelter in the winter of 2007. The following year, the Montessori school took over.

Today the colourful jungle gyms and live chickens in its backyard are a world away from the grim vision of ill discipline and desperate teachers seen in The Wire. Allison Shecter, its founder and director, says: “We have younger kids here whose parents come from every zipcode in the city. We do bring kids in at every age. They come in when it [their schooling] isn’t working : they have a hard shell so it takes a while to win their trust. Even when they come in at eighth grade, it’s transformational.”

The Montessori has 425 pupils and a waiting list of 1,200. It draws pupils by lottery from across the city, many from middle-class homes, while kids in the surrounding, struggling neighbourhood often do not make it and go to Dallas F Nicholas instead. The dynamic has provoked debate about parental choice, the lack of resources for government schools and the dangers of rivalries.

Shecter, 47, says: “Families are looking for choice. If there are schools struggling, I think looking at why schools are struggling and helping them needs to be the answer rather than pitting them against each other.”

She acknowledges that Greenmount West continues to have problems. “It’s still very much a neighbourhood in transition: there are still drugs and gangs. There was a hold-up with a gun at eight o’clock yesterday morning. Crime in Baltimore is out of control.”

But Tina Knox, 57, whose nearby backyard also featured in The Wire, is upbeat. “At one point in time this community was down to nothing,” she says. “You don’t know if a fight’s going to break out or they’re going to start shooting. But once they started tearing down the vacant properties, investors started coming in, buying the houses and fixing them up. The community is coming back up. Now you couldn’t pay me to live in any other neighbourhood.”

Her friend Stewart Watson has lived here for 15 years and runs an art gallery. Today she is out walking her two great danes. “I didn’t watch The Wire because I felt I was living it,” Watson recalls. “It wasn’t relaxing to me because of what was happening in my community at the time. The one about schools would probably break my heart.”

The closure of the school was a heavy blow, she recalls. “All the kids got sent to other schools. Not having a school in the neighbourhood was really tough. It changes the dynamics of the families and breaks up the camaraderie of a neighbourhood. It was the school where Tina went: that kind of loss you can’t recover from.”

Watson, 48, is “optimistic but also worried” about the future of Greenmount West. “There are difficulties with the gentrification process that any community has. Gentrification is a half-dirty word. I’ve said if it means I don’t have spinning bulletproof glass up the street, that’s great. It’s about what’s fair and accessible: the racial divide that plagues this city we’re still trying to figure out.”

A short drive away, reminders of that divide are everywhere at some of The Wire’s most fondly remembered locations. The boxing gym where Dennis “Cutty” Wise (Chad Coleman) gets back on the straight and narrow is abandoned, its windows broken, cesspools and debris on the concrete floor, the silhouette of a boxer painted on the wall a reminder of its ghosts. (There is talk of a food co-op moving in.)

The TV repair shop that was run by drug kingpin Proposition Joe and the bar that belonged to Omar’s confidante Butchie have both closed down. Michelle Sponaugle, 53, whose father owned the latter, says: “It makes me sad. I used to work behind the bar. We had a good clientele but the crime got rough down here. My father had a gun put to his head a couple of times so we put up a bulletproof wall.”

And the convenience store where Omar, the seemingly invincible stick-up man (“You come at the king, you best not miss”), was gunned down by a boy has vanished altogether after a blaze set off by the unrest of 2015 and the construction of an apartment complex for the elderly. Over the road is a park bench that proclaims without a hint of irony: “Baltimore: the greatest city in America.”

One of its occupants, Alfred McDaniel, 59, says he never saw the series because he does not watch TV. “Time is too valuable to waste so why would I do something like TV? I’m in a house that should be condemned, so why would I watch TV? I’m in court trying to get them to fix it. I need surgery but I’m trying to deal with the rats and the mice. Where I live, the stupid landlord won’t even fix the goddam door.”

McDaniel, a home repair man on medical leave, is in his fifth home in five years in the city. “I ain’t seen no improvement in Baltimore. You call the police to report a crime and they tell you they’re not going to file a report, so what police can you depend on in this city? So the next person who breaks in your room, you should kill them.”

Beside him is John Williams, 56, who used to work on the docks, which featured in the show’s second season. He says: “Baltimore is struggling the same. It’s good for some people but if you live on this side of town it’s not that good. Houses have been vacant a long time so there’s no reason for homelessness in Baltimore. The city could try to renovate these houses and make them affordable to people.”

Williams says that, in his first week as a resident of Baltimore in 2013, some 35 people were killed. “The cops are overwhelmed to a certain degree. Relations are strained. The community doesn’t believe in the cops. There are people who know who committed murders but they don’t want to come forward. You’ve got murderers walking among you and it’s dangerous, basically. If you’re working as a taxi, you’ve got to be careful where to pick up.”

Similar sentiments are expressed in another neighbourhood by Janet Worsley, 57. “They still have gangs and mobs. You take your life in your hands if you walk these streets at a certain time of night. If I get off work, I walk home, but to come out otherwise? No.” She describes an incident when her car was stopped by police. “All I could do was humble myself: ‘Sorry, officer.’ I’m still afraid for my son being mishandled by police because he has a mental illness.”

For Sonja Sohn, such issues resonate with her own childhood and remain intensely personal. After production wrapped on the fifth and final season she co-founded ReWired for Change, a Baltimore-based nonprofit organisation that works to help young people break the cycle of crime. It often uses cast members and material from the show to get its message across.

For a while, it seemed this portrait of a city in crisis might sting officials into action, but the power of art has its limits. Sohn says: “I think that the city leadership did begin to make an effort to look at the issues that The Wire brought to life, particularly because of the fourth season, which focused on the children and the schools.

“As much as the city leadership couldn’t stand The Wire, they were forced to address the issues because, I believe, they wanted to prove that their city was better than what was depicted. So ultimately The Wire impacted this city in a positive way in my opinion.”

But then came a hammer blow that appeared to destroy any putative gains made in crime reduction and community-police relations in Baltimore. Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old African American, died of neck injuries suffered in police custody in April 2015. The city erupted in weeks of mass demonstrations and a day of rioting. Six police officers were charged in connection with Gray’s death but none was convicted. A justice department report found a huge racial disparity in enforcement, especially in stops, searches and discretionary misdemeanour arrests, including those of people congregating on street corners. It also observed that residents believe there are “two Baltimores” – “one wealthy and largely white, the second impoverished and predominantly black”.

Sohn says: “I was not surprised but the most visceral reaction I had was one of support of the people. I was so tired of pounding the pavement, of spending my extra time and extra dimes to help lift up under-served communities in Baltimore. After I started the nonprofit, I started to see how challenging that work is, and I also started to see how it quite possibly is this never-ending clusterfuck. I had stepped away to reassess how I could be useful, in fact, when the whole Freddie Gray situation happened.

“When I saw the people rise up and express their anger in the way that they did – even though I did not want the city to burn down, I did not want lives to be lost – the very core of me said, what else could they do to get your attention? To let you know you serve them? That you have not served them for decades, and they’re not tolerating it any more? They put you in office, the city taxpayers pay their salaries, and they’re not being served. And when talking no longer works, what else do the people have?

“That part of me said, burn it down, burn the whole motherfucker down. If they’re not going to fucking listen, burn it. There’s that revolutionary radical in me. But at the same time that’s more of a sense than it is an intellectual choice I’m telling people to make. I’m saying yes, act from that sense. We don’t want them to take it literally but I see you acting from that sense and, symbolically, this is what we need to do. We just need to find a way to do it differently.”

Relations with the police remain strained despite efforts and initiatives on both sides. Sohn is eager to dispel the myth that young men hanging out on streets corners or residents sitting on stoops outside their homes are all selling drugs. “I think what people don’t understand is when you live in these communities, this is your tribe, this is your home, the streets are a part of your property, it’s a part of your culture.

“We sit on the stoops, we say ‘Hey!’ to Miss Mary down the street and see the little kids coming home. If there’s a fight, somebody jumps off the stoop and runs and breaks up the fight. We might not use drugs or deal drugs but we know the drug dealer, we babysat him when he was eight. Or maybe we know he’s 20 and he’s dealing drugs but we went to school with him – ‘He was in my eighth grade class’. These are just people we know. ‘We know your mama, I date your sister, she cool’.

“What’s going on on the street isn’t always drug dealing. It’s a community that’s gathering and taking care of itself. If you don’t understand it and you’re only looking at TV, what you’re thinking is people are dealing drugs and everybody’s just depressed and sitting on the stoop drinking beer. And though that may be there, it is certainly not all of what’s there. There’s a community gathering and communing with one another.”

Nevertheless, the toxic mix of drugs, firearms and joblessness chronicled by The Wire in 2002 still persists. Last month, the mayor of Baltimore, Catherine Pugh, appealed to the FBI for extra help to combat the soaring homicide rate, explaining: “Murder is out of control. There are too many guns on the streets.”

Rafael Alvarez, an author and screenwriter who worked on the show, writes in an email: “The rich and cruel supply of American fucked-up-ness will never run dry in Baltimore, so yes, The Wire could be made 15 years after it originally aired. I suspect – give or take 50 homicides and a new wave of corruption and ignorance – it could be made again 15 years from today.”

Olesker is similarly short on optimism about the city’s future. “I think you could do the same show today. It’s still out there on the street corners: you can go to countless neighbourhoods and see street after street of abandoned houses that have sat there for years.

“You’ve got all these kids who are rootless, who don’t have families, who are joining gangs. They’re figuring out very early the game is stacked against them. They’re not going to get to college like middle-class kids do, so they have a choice: they can work in McDonald’s for $10 an hour or they can make multiples of that from the drug trade, and there’s no mother or father around to tell them otherwise.”

Indeed, Donald Trump’s pledge to be a law and order president stressing “blue lives matter” rather than “black lives matter”, and his attorney general Jeff Sessions’s retro approach to tough sentencing only seem likely to fan the flames in Baltimore, a majority black, staunchly Democratic city. The Wire was sometimes accused of implying that its characters were locked in a hopeless cycle; events seem to bear out this sense of fatalism.

But Kwame Kwei-Armah offers hope. “One of the things I’ve learned since I’ve been here is that people of Baltimore care about Baltimore in a rather profound way. I’m talking about the philanthropic community in particular: they actually put their money back into the community. Community means something, and I’m not just saying that to blow smoke. We had to raise $36m in order to renovate our theatre and we were able to do that in what is a relatively small city. We’re not the only people out with a capital campaign. Actually, after the uprisings of 2015, there was a lot of money that came from within Baltimore to start looking at creating solutions for the problems that are endemic here.”

Sonja Sohn, too, feels some optimism. “I’ve been around, I’ve been on the planet a little while,” she says. “I never trusted the establishment anyway so the face we are seeing now is not a surprise, and I’ve also been around long enough to see people and movements come and go. By no means do I believe that evolution goes backwards. Evolution goes forwards. No human being can defy the laws of nature, so I’m not worried about Donald Trump and I’m not worried about Jeff Sessions. I’m on my mission, I’m on my grind, I’m on my purpose and we are all collectively moving forward, I guarantee you that.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion