It seems like a day doesn’t go by without some sort of controversial brain-related study coming up in the media. It’s a phenomenon that is born out of the fact that brains are inherently interesting objects; everyone has one, everyone loves them. But all too often, as has been pointed out countless times before, the explanatory power of specific neuroscientific studies gets overplayed. Thankfully, a plethora of excellent neuroscience blogs are around to help clarify the good science, and debunk the bad stuff that’s out there.

But brains don’t just crop up in the realm of science alone. Increasingly, we’re seeing an explosion of so-called ‘neuro-isms’ – neuropolitics, neuroeconomics, neuroethics, neuroaesthetics... The list is seemingly endless. All are based on a basic assumption that we can gain a deeper understanding of some area of interest by delving into the inner workings of the brain. Perhaps the most controversial of these areas of research is neuromarketing.

The grand claim of neuromarketing is that we can figure out things like differences in consumer preferences, or how shoppers go about making decisions, based on recording brain activity. The argument goes that this is better than simply getting consumers to fill out questionnaires, or taking part in interviews, because sometimes people are pesky and annoying, telling you that they do or like one thing when in actual fact they do or like another. By looking at patterns of brain activity, you remove this sort of subjective bias, and tap into what the consumer is really thinking. Or so the argument goes.

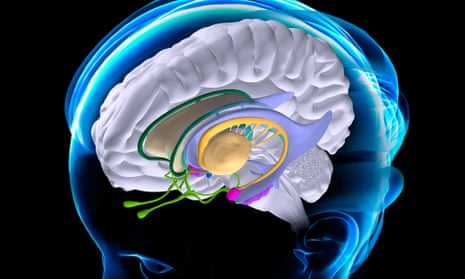

One problem with neuromarketing is that brains are pretty complex things, and neuroscience is still trying to figure out how they work. Accordingly, brain imaging and analysis techniques are quite involved, and there are a considerable number of pitfalls you can encounter in trying to interpret the data. The other problem with neuromarketing, is a worrying number of people in the field seem to all too readily gloss over this issue.

Volvo are the latest company to jump on the brain bandwagon. Last week, a new marketing campaign claimed that ‘car design is proven to be on a par with the most basic of human emotions’. Not ‘shown’, or ‘suggested to be’, but proven. As the great Carl Sagan once said, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, so what data do we have to back up this claim?

Not much, as it turns out. The press release points to a survey and a small EEG study. The experimental study used an off-the-shelf, ‘dry sensor’ EEG device that houses two electrodes that recorded activity from the front of the brain. Participants were asked to view a number of pictures of a new concept car, alongside pictures of ugly cars, happy or crying babies, and attractive men and women. According to the results, men ‘experienced more emotion whilst looking at images of beautiful car design than they did whilst looking at an image of a crying child’. Women ‘displayed an emotional intensity to the picture of a crying baby which almost doubled that of male participants’. Right.

We can’t figure out too much more about the study, because the experimental details are so sparse. The data didn’t come from a peer-reviewed, detailed journal article – they’re explained in 200 words in a press release. So we don’t know how many people were tested, what sort of controls were put in place, or how the data were analysed. Moreover, as I and others have discussed before, one of the disadvantages of EEG is that because electrodes are so big, and neurons are so small, you need a large number of sensors in order to get anything resembling meaningful data. With two electrodes, you’ll certainly be able to pick up some brain activity, but localizing and inferring anything about specific types of neural processing from it is next to impossible. So you can’t talk very specifically about sex differences in the presence of positive or negative emotions in this experiment, because the data will simply be too poor.

The company behind the experiment is MyndPlay, and the marketing campaign is bolstered by quotes and interviews with self-proclaimed ‘father of neuromarketing’, Dr David Lewis. Lewis is no stranger to these sorts of studies – a similar experiment was commissioned by Standard Life a few months ago to look at how emotions are linked to attitudes towards saving for the future. In 2007, he announced that chocolate was better than kissing, after conducting research in partnership with chocolate makers Cadbury. And last year, he came up with the formula for the perfect holiday – in association with Holiday Inn. In all instances, the research that’s involved appears to be little more than PR in an ill-fitting science suit - advertising guff interspersed with vague references to the brain. The danger is that it makes scientists seem detached from reality, and more interested in five minutes of fame rather than actually making a useful point about anything. It’s boffinry at its worst.

Brain recording technology, like EEG, is difficult and time-consuming to use, and even in optimal circumstances won’t necessarily produce a clean and simple answer. That doesn’t mean that it’s useless; just that we need to be wary in taking a sledgehammer approach to using it wherever and whenever. If someone does, they seriously damage the credibility of neuroscience in general, and do a great disservice to the many brilliant people actually doing serious work in the field.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion