It was once the home of radical talk, where subversive thinking was encouraged and a cup of trademark mediocre coffee came with a complementary side-order of socialist discourse. London’s Partisan Coffee House, the 1950s Soho venue that gave birth to many of Britain’s leading leftwing movements and campaign groups, will be the subject of an exhibition next month that will feature newly discovered photographs of its heyday.

Pictured in black and white on the walls of the Four Corners gallery in Bethnal Green, east London, will be many of the renowned clientele of the Carlisle Street cafe, where the occasional undercover police officer posed as a chess-playing customer in order to eavesdrop. Among its regulars were influential 20th-century intellectuals, including the social and cultural theorists Stuart Hall, John Berger and Raymond Williams, as well as the film-makers Karel Reisz and Lindsay Anderson, the novelist and Nobel laureate Doris Lessing and the folk singer Peggy Seeger.

“It was a beacon of a certain kind of non-aligned leftist politics that we think of now as the New Left,” said exhibition curator Michael Berlin, a historian at Birkbeck, University of London. “Much of the thinking went against all the orthodoxies, so these people were rejecting Stalinism, and distancing themselves from what Britain was doing in Africa – and Kenya in particular – and they were against the acquisition of nuclear weapons.”

Berlin, a specialist in London’s cultural history, came across photographer Roger Mayne’s unused images of the coffee house on a forgotten contact sheet stored in the vaults of Bishopsgate Institute’s library in the City of London. Before the pictures go on display alongside film clips and magazine covers on 5 May, Berlin hopes to find any government files still held that record the routine surveillance carried out at the cafe.

“I know that Special Branch officers used to come in and play chess so that they could listen in to the conversations,” he told the Observer. “Mayne’s photographs are a great record of the first coming together of many of the people behind the counter-cultural revolution that was to come in the 1960s, and the genesis of organisations like the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Some of the images are quite obviously set up, but Mayne may have been there with his camera on more than one occasion as there are some evening shots.”

The cafe was set up in 1958 by the radical historian Raphael Samuel, with the help of Hall and the Marxist academic Eric Hobsbawm, partly as an antidote to the flashy Italian coffee bar fashion taking hold in the capital. It was also intended to support Samuel’s socialist History Workshop Journal, and to fund the magazine Universities and Left Review. Initial investors included the actor Michael Redgrave, the Observer’s theatre critic Kenneth Tynan and the novelist Naomi Mitchison.

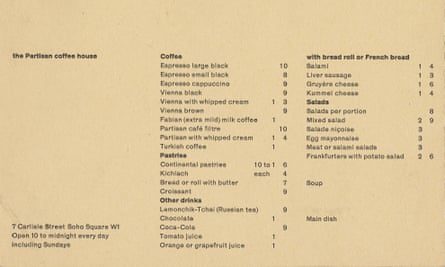

Billed as London’s first anti-espresso cafe, it served filter or “Partisan coffee” which even Hall once admitted was not up to much. Also on offer was “Fabian coffee”, described as “milky”. The idea was that customers could sit over one drink all day if they wanted.

“The cafe marked a moment in social history,” said Berlin. “It was here that the CND’s ‘Committee of 100’ was named and the first Aldermaston marches were arranged. The cafe staged a series of debates and it was part of the effort to get the Labour party to put disarmament into its manifesto, which it failed to do. Samuel’s History Workshop movement was an attempt to popularise the study of history, so that the people themselves were contributing to it.”

But the ethos of the cafe was not entirely “po-faced”, according to Berlin. There was room for wider cultural fun. “They were interested in film, in beat poetry, and they had folk and skiffle bands play.”

Alongside frequent visitors such as Berger, the author of Ways of Seeing, who died in January, Anderson, the director of If...., and Reisz, the director of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and The French Lieutenant’s Woman, notable fans of the Partisan Coffee House included Quentin Crisp, the author of The Naked Civil Servant, the poet Christopher Logue and the singer Rod Stewart. The designer at Penguin Books, Germano Facetti, was responsible for several magazine covers, while the influential graphic designer Desmond Jeffery created the in-house menus and posters.

Lessing was a frequent speaker at the cafe, but Mayne’s photographs reflect women’s more usual backroom role. “They were present, but this was a place of its time, so it was run by men. A lot of the hard work was done by women though, and many of them went on to be part of the new wave of feminism,” said Berlin.

He suspects the name “partisan” was chosen for its rebellious cachet and because it carried a hint of the respect around at the time for the Yugoslavian partisans who had fought the Nazis under Tito. “It represented an alternative lifestyle that appealed to beatnik outsiders. It was a moment of youthful optimism in a very dark time,” he said.

But far from supporting the journal, the coffee shop lost money and eventually closed in 1962.

“The old shop is next to Private Eye’s building in Carlisle Street. At the time it had a strikingly modernist stripped pine interior, but it has been converted into offices now. It was the home of a PR company for a while,” said Berlin.

In a grim joke, the lettings agency now in charge of the site mentions the coffee house in its details for the property. A boldly radical 1950s venture has become a quirky commercial selling point.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion