Babies Floating in Fluid-Filled Bags

A lab has successfully gestated premature lambs in artificial wombs. Are humans next?

When babies are born at 24 weeks’ gestation, “it is very clear they are not ready to be here,” says Emily Partridge, a research fellow at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Doctors dress the hand-sized beings in miniature diapers and cradle them in plastic incubators, where they are fed through tubes. In many cases, IV lines deliver sedatives to help them cope with the ventilators strapped to their faces.

Each year, about 30,000 American babies are born this early—considered “critically preterm,” or younger than 26 weeks. Before 24 weeks, only about half survive, and those who live are likely to endure long-term medical complications. “Among those that survive, the challenges are things we all take for granted, like walking, talking, seeing, hearing,” says Kevin Dysart, a neonatologist at the Children’s Hospital.

But within a decade or so, babies born between 23 and 25 weeks might not be thrust into the harsh outside world at all. Instead, they may be immediately plunged into a special bag filled with lab-made amniotic fluid, designed to help them gestate for another month inside an artificial womb. That is, if a new technology that has been successfully tested on lambs is found to work on humans.

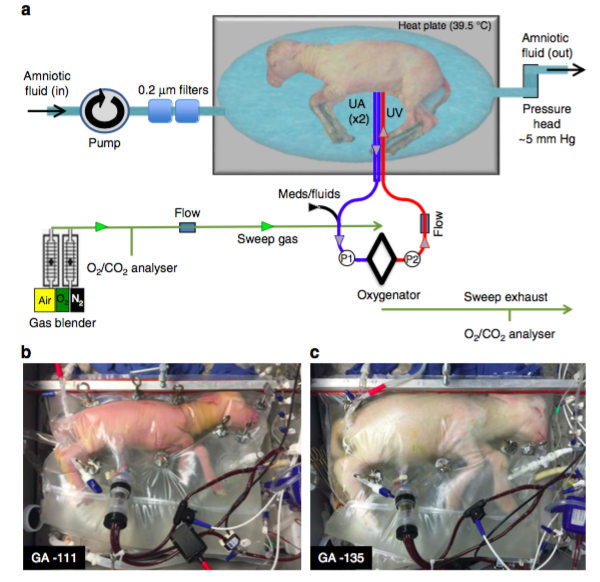

For a study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications, Partridge and other researchers from Philadelphia suspended premature lambs, a close animal model for human fetuses, in a liquid-filled, artificial womb, allowing them to further develop for four weeks—longer than in past similar attempts.

The researchers used eight lamb fetuses that were 105 to 115 days old—a level of development comparable to a 23-week-old human fetus. As they floated, the lambs’ brains and organs developed normally. The pinkish creatures opened their eyes, fattened up, and grew coats of white wool.

The researchers anticipate the animal studies will be completed within two years, and if approved, the wombs can be tested on human preemies within three to five years.

One reason preterm birth is so dangerous is that, for an underweight baby, the first few breaths of air halt the development of the lungs. “Infants that are currently born and supported in a neonatal intensive care unit with gas-based ventilation demonstrate an arrest of lung development,” Partridge says, “which manifests in a long-term, severe restriction of lung function.”

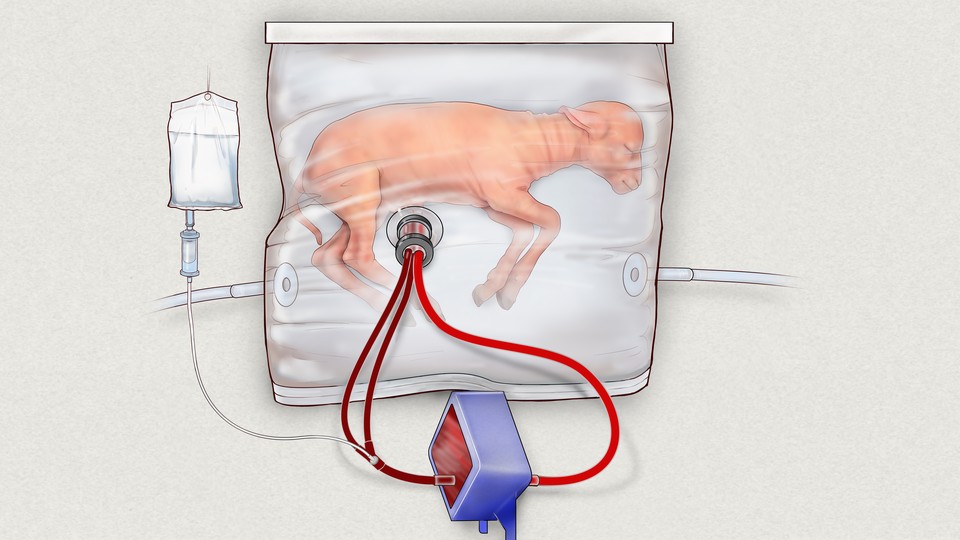

With the artificial womb, the infant would continue “breathing” through the umbilical cord as its floats in amniotic fluid, which would flow into and out of the bag. Using its tiny heart, the fetus would pump its own blood through its umbilical cord and into an oxygenator, where the blood would pick up oxygen and return it to the fetus—much like with a normal placenta. In addition to boosting lung growth, the amniotic fluid would protect the baby from infections and support the development of the intestines.

The babies who are hooked up to this apparatus would need to be delivered by C-section, as 60 percent of extreme preterm babies currently are. During the operation, the fetus would be given a drug that would prevent it from taking gulps of air during its brief brush with the outside world. Within seconds, it would be submerged again in the polyethylene bag, just like it was in the womb.

“I don’t want this to be visualized as fetuses hanging on the wall in bags,” said Alan Flake, a fetal surgeon at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and an author of the study, on a call with reporters.

He says it will look similar to a traditional neonatal incubator, potentially equipped with a camera to assuage anxious parents. The doctors could even pipe in the mother’s heartbeat. It’s “less stressful than seeing an infant on an incubator on an exposed bed,” Flake said. “That’s a very distressing environment for parents.”

Many hurdles remain in translating the lamb research to human babies. Artificial uteruses have been tried—and failed—before. A 1996 New York Times Magazine story declared “the artificial womb exists” and described a Tokyo lab in which baby goats floated in a heated, fake amniotic suspension. But, alas, it all ended in technical issues and circulatory failures.

In this case, the researchers don’t know if the lamb umbilical vessels will function identically to those of a human fetus. Lambs are also several times larger than humans are at that stage of development.

If they ever materialize, artificial wombs may stir concerns among pro-choice advocates, since the devices could push the point of viability for human fetuses even lower. That might encourage even more states to curtail abortions after, say, 20 weeks’ gestation. But speaking with reporters Monday, the Philadelphia researchers emphasized they don’t intend to expand the bounds of life before the 23rd gestational week. Before that point, fetuses are too fragile even for the artificial wombs.

Instead, they say their aim is to make extreme prematurity claim fewer infant lives, as well as to reduce the estimated $43 billion that prematurity costs the U.S. medical system each year, according to a hospital statement.

In essence, it’s to make it so babies who shouldn’t quite be “here” yet don’t have to be. In a video that accompanied the release of the study, Partridge described being struck by the sight of the zipped-up lamb fetuses, “breathing, swallowing, swimming, dreaming”—all with “complete detachment from the placenta and from mom.”