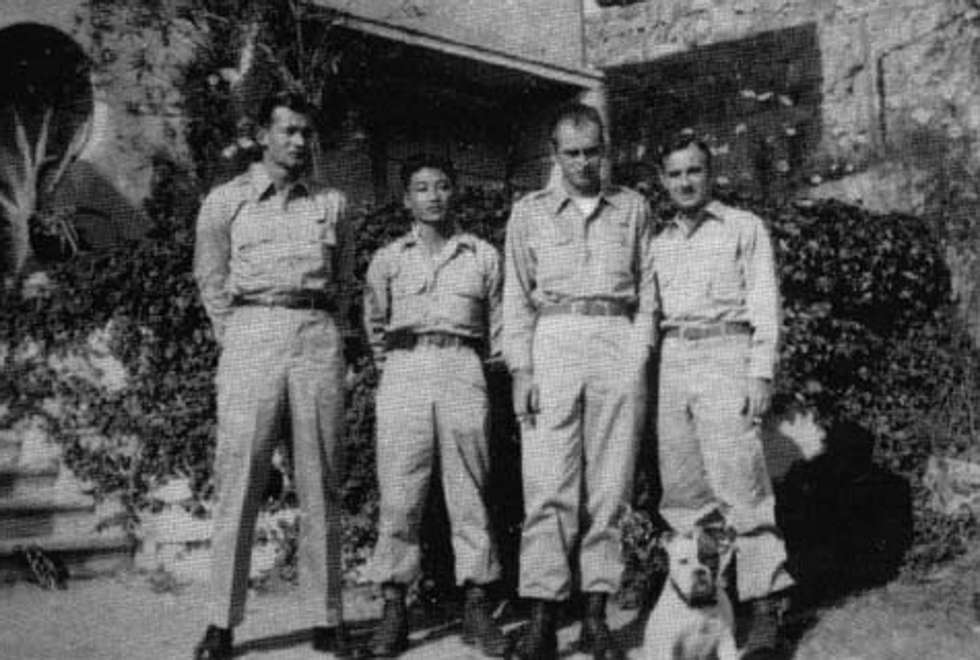

Eric Liddell’s former roommate in China internment camp celebrates his centenary and the time of his life

Olympic runner immortalised in Chariots of Fire would have been best man at my wedding if he’d lived, says Joe Cotterill, who met the two loves of his life in the Japanese wartime Weihsien internment camp in Shandong province

About 15km from the spires of the university city of Oxford, Southmoor is a pretty village, with listed buildings and a couple of pubs; just the kind of place you would expect to stumble across while exploring England’s leafy country lanes. A birthday celebration at the village hall is a common occurrence.

Not so commonplace was the birthday party held in the hall one Saturday in March for Joe Cotterill. The trimmings included a cake in the shape of “100”, a card from Britain’s Queen Elizabeth (whom Cotterill met a few years earlier), a champagne toast and origami peace cranes.

Becoming a centenarian is a reason to celebrate, and Cotterill’s big day certainly rose to the occasion, bringing together some 110 people who had played a part in his long and varied life; family, friends, neighbours and colleagues, some of them travelling from as far afield as America and Taiwan. Among the sea of smiling, often emotional faces were five pensioners – a man and four women, alive for 425 years between them – who had been in the same Japanese internment camp as Cotterill during the second world war.

The Weihsien camp, in Shandong province, was to be a major influence on Cotterill’s life.

He met and married his first wife, Jeanne Hills, within its walls and then, during post-war reunion events, got to know another former inmate, Joyce Stranks, who would become the then widower’s second wife on Valentine’s Day, 2002.

“China was a highlight partly because I got married there and partly because of the people I met,” says Cotterill, when we speak after his party. “So much has happened since, it’s difficult to say which is the best period of my life, but China was one of the crucial things.”

I saw the rescuers coming, we all ran out of the camp to let them in. We carried them on our shoulders and as we got to the entrance the band started playing. It was very emotional

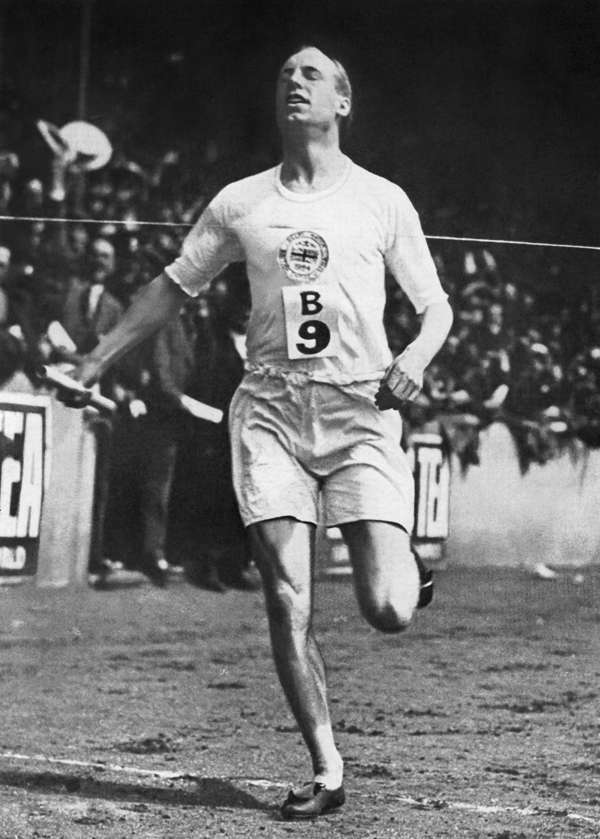

Peter Bazire, 86, performed briefly at the birthday bash. He played the same tune on the same trumpet he had used as a teenager in the camp’s Salvation Army band to comfort Eric Liddell, the Olympic runner and missionary who was immortalised in the 1981 movie Chariots of Fire, as the fellow internee lay dying in February 1945.

“We thought he was having a nervous breakdown; we had no means to diagnose him,” he says. “When Peter Bazire began playing the trumpet at my party I closed my eyes and remembered where I’d been standing in the camp when I heard that music, Be Still My Soul. I was in the hospital laboratory and the band were outside. I think I’d introduced Eric to that hymn. It was very moving, and then the linking of it all together for my birthday moved me again.”

After the war, Bazire – who had been a pupil of the Chefoo School (in what is now known as Yantai, in Shandong) before being interned – wouldn’t play the trumpet again until he was 70.

Life in a Chinese treaty port: Eurasian traces great-grandparents’ journey from London slum to Hong Kong and beyond

“It was very cold in China when we played for Eric Liddell, but you can’t play a trumpet with gloves on and there were no health and safety rules then. We had chapped lips and chapped fingers,” says Bazire. “I’m not a classy trumpeter but I was honoured to play for Joe on the old trumpet, which I’d kept for sentimental value. It represented that period of his life.”

Cotterill, from Chapeltown, near Sheffield, in Yorkshire, northern England, was the fourth of five children. His father was a coal miner and he acknowledges his life would have been very different if he hadn’t passed a 1920s exam that gave him a grammar school scholarship.

“Otherwise I would have probably become a miner,” he says.

After the family moved to Manchester, Joe continued to study while working in a chemist’s laboratory. He also began learning Putonghua through a missionary organisation. In late 1939, at the age of 22 – as war clouds formed over Europe and the Japanese expanded their Asian empire – Cotterill left England.

“My brother was in the army because of Hitler,” he says. “I had three sisters, but for my brother to be away and me off to China, my parents were not so pleased.”

We thought {Liddell] was having a nervous breakdown; we had no means to diagnose him

Cotterill had been accepted as a missionary after an interview in London, his first time in the British capital. Soon he was heading through France and Switzerland on a train. He was delayed for a while after Hitler invaded Poland on “that Friday morning”, but the eager missionary finally sailed for China from Italy, on an Italian ship: “It was cheaper than the others.”

“I initially thought that by going to China I was getting away from the war, even though China was already partly occupied by the Japanese. I did wonder what I was getting into, but I was young.”

Having landed in Shanghai, Cotterill went north, to Kalgan (now Zhangjiakou, in Hebei province), “the Japanese capital” of the area.

“I arrived on October 30, 1939, and was immediately introduced to Halloween, as the American mission hospital invited us over for a party.”

The language, culture and food in northern China were new to the young Englishman. He began wearing Chinese clothes and played the accordion for services led by senior missionaries. He also studied Putonghua and Mongolian.

Cotterill was not in Kalgan for long. After less than a year, the Japanese arrested his Chinese teacher, a young man of military age, and “my Mongolian teacher suddenly had urgent business the other side of the Gobi Desert”.

Senior missionaries were heading to Beijing so Cotterill decided to follow them; he could continue studying in the capital, he reasoned. He had difficulty getting permission from the Japanese to travel but was finally successful in August 1940. Cotterill undertook missionary work in Beijing, teaching in a Bible school and helping to establish a church just outside the city.

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour, in December 1941, the crackdown on foreigners in China intensified and missionary work was suspended. For more than a year, foreigners in Beijing were under city arrest, unable to leave and ordered to carry identification.

By this time, Cotterill was working as a youth leader for expatriate children and recalls a visit to a lake in Beijing with them: “It would freeze over in winter so I learned to skate with all these youngsters around me. I was asked if I would play a game called ‘crack the whip’. I didn’t know how but said I would learn. We all started off together but someone let go of my hand and I went flying. The best way to stop was sit down.”

Cotterill and Stranks’ paths first crossed in Beijing, 60 years before they became man and wife. He remembers being hit on the arm by a snowball thrown by a 14-year-old.

“My friend and I were throwing snowballs at people coming to church – particularly handsome young men,” says Stranks, who had arrived in China as a baby, with her Salvation Army parents. “I got direct hits on a man called Marcy and also on Joe, both of whom I married.”

In March 1943, many foreigners in Beijing were sent to Weihsien. The British contingent travelled by train “in two very crammed, locked carriages with armed Japanese guards in each”, says Stranks.

At the end of the journey, they found themselves in a camp with more than 1,400 Allied nationals, a mini United Nations of missionaries, diplomats, children and businessmen and women, as well as thieves and prostitutes. More than two years would pass before they would again taste freedom.

The Weihsien Civilian Assembly Centre, as the Japanese referred to it, was established in an American Presbyterian mission compound named Courtyard of the Happy Way. The compound consisted of 10 hectares filled with shrubbery and fine old trees. Walls with barbed and electrified wires surrounded the camp, watched over from guard towers on the perimeter. Weihsien held up to 1,800 people; families were kept together in small rooms, while what had been classrooms and hospital wards housed single men or women.

When Peter Bazire began playing the trumpet at my party I ... remembered where I’d been standing in the camp when I heard that music, Be Still My Soul ... I think I’d introduced Eric to that hymn

“There were also a lot of weddings in the camp,” says Cotterill. “With the war coming to an end, and, as in my case, a couple being from different missions, you didn’t know if you’d be sent to different parts of the globe. So it made even more sense to get married.”

Cotterill married Hills on May 5, 1945, just before the end of the war in Europe.

“At 2am on May 6 we had to go outside for roll call because two youngsters had got into the tower building to ring the bells. They didn’t know the bells were only to be rung to warn the Japanese army camp nearby that guerilla forces were attacking us. We all had to be counted, to see if anyone had escaped. So that was our wedding night.”

On August 17 – Stranks’ 18th birthday and a week after the second of two atomic bombs had been dropped on Japan – Weihsien was liberated by six American airmen and their Chinese translator, Wang Chenghan, who is now 92 and e-mailed Cotterill a 100th birthday greeting from his home in Guizhou province. Remembering that day when seven brave men parachuted from a plane to free the camp, not knowing if the Japanese guards would fight back (they didn’t), Cotterill says, “I saw the rescuers coming, we all ran out of the camp to let them in. We carried them on our shoulders and as we got to the entrance the band started playing. It was very emotional.”

After the ordeal of internment, the newlyweds returned to Britain (in 1949 the communists would expel all remaining missionaries from China). They had a son – Cotterill now has two grandchildren and two great-grandchildren – and the new father found work in atomic energy and at the Home Office.

After Hills died, in 1988, and he had retired, Cotterill was alone at home in Southmoor.

“I went to help in the church and the vicar said, ‘Why not get ordained?’ So, in 1993, when I was in my 70s, I was ordained and a new life started.”

He also met Stranks again. She had spent many years in Taiwan with Marcy Ditmanson – who became a doctor after leaving Weihsien. Her first language growing up had been Putonghua and she often translated for him and his colleagues. Even now, Stranks and her second husband sometimes converse in Putonghua “although his was learned in school, mine was learned on the streets of Beijing”, she says.

The couple travel regularly and spend much of their time in the United States, where some of Stranks’ six children live. They have been back to China, most recently in 2015, for the 70th anniversary of Weihsien’s liberation. The former camp is now a memorial site.

“It was very nice to see the refurbishment and memorabilia,” says Stranks. “They had a wax model of Eric Liddell in bed. He had been very ill, but the model of him is sitting up and smiling.” She remembers visiting the Olympic champion on the day he died. They talked about a book that dealt with surrendering to God, she recalls. As she stood by his bedside, he struggled to say the word “surrender” and then he went into a seizure. He died that evening.

Actor Joseph Fiennes, who played Liddell in The Last Race (2016), a film co-directed by Stephen Shin Kei-yin and Michael Parker, spoke at length with Cotterill and Stranks as he worked to gain an understanding of his character for the film.

Cotterill describes his 100th birthday celebration as an emotional affair, “especially when I was saying thanks to some of the young people I’d known; a lot of them are now 60 or 70 and I hadn’t seen them for years.”

The occasion was a chance to remake acquaintances and share memories. For those who live on, says guest Kathy Foster, 86 – who was born to missionary parents who met on a raft in China and, like Bazire, is a former pupil of Chefoo School – Weihsien has been a “binding force”.

“I knew Joe in Weihsien because he married Jeanne, my English teacher. After the war I didn’t meet him again until I retired and moved nearby,” she says. “By then, he had married Joyce, who I also remembered from camp: she once borrowed a ball from Eric Liddell and threw it over the wall by mistake. She climbed over, risking life and limb, got the ball from under the electrified wire, but could not get back over the wall. Her friend saw a tall priest nearby and got him to give Joyce a hand.”

Jean McDermid, 73, was born in Weihsien, in September 1943, but remembers nothing of the camp. Her grandfather founded the Beijing School for the Blind and Liddell was the best man at her father’s first wedding.

“Joe’s birthday party was a very happy family occasion and a celebration of Joe’s varied life,” says McDermid, who met Cotterill and Stranks for the first time last year. “Weihsien formed an important but short part in this. For me, as Weihsien was my link with them, the party was a very special and moving occasion. It was interesting to meet people with memories of the camp.”

Margaret Holder, 91, another guest and former Chefoo School student, was interned in Weihsien with her brother. She remembers Cotterill as “tall and handsome and married Jeanne, one of our teachers”.

“They had a little attic room at the top of the old hospital block. We tried to give them some privacy by collecting their water and meals. Jeanne wrote us a thank you letter, which I kept,” she says. “I showed it to Joe at the party.”