In a quiet corner of Essex, spring is breaking through. Sun lights up the fields between two converted pig sheds, one of them hosting a band’s history, the other its present. Two men in their late 50s settle in the former: the taller, a gentle headmasterly type in a cable-knit jumper and glasses; the shorter, a bleached-blond imp in plaid jacket and scarf. Nearby is a huge archive of computers, synthesizers and tapes that tell their long story. It’s a remarkable one: from a resolutely unsuccessful 1980s, through a hugely fruitful 1990s, to a 21st century that has included online ventures, long periods working independently, and soundtracking the biggest festival of all – the 2012 London Olympics opening ceremony. Across a gravel path is their recently renovated live studio, where their future – together again – is thriving.

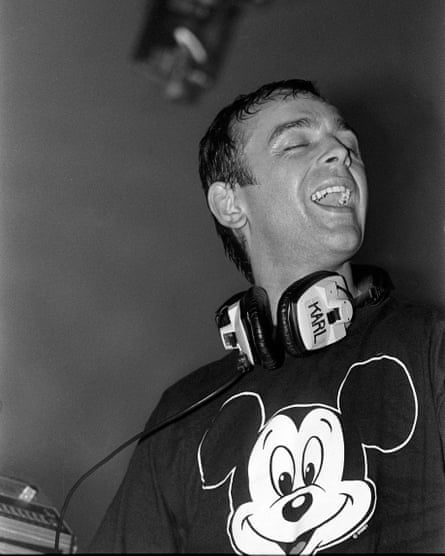

“Thing is, we were never really apart,” says Karl Hyde, Underworld’s lyricist, singer, guitarist and strangely mesmerising frontman, who, unbelievably, turns 60 next year. He’s right in a way. Even though he has spent recent years making albums alone (2013’s Edgeland) and with Brian Eno (2014’s Someday World and High Lifecorrect), while the man sitting next to him, Rick Smith, has collaborated with film director Danny Boyle, they have played live over 50 times since their last album, 2010’s Barking. It was in their more recent gigs together though, revisiting the album that changed their lives, 1994’s Dubnobasswithmyheadman – that a new chapter was born.

“Going out and [playing that record] was a reconnection with how much I love this music, how much I love what Rick does,” says Hyde. “It didn’t matter what state of mind I was in – ideas were being kicked off all the time.” Dubnobasswithmyheadman was 20 years old in 2014, and to mark the occasion the duo toured Europe, playing the album in full.

An extraordinary melding of wayward street poetry, dark atmospheres and propulsive, hook-filled techno, it was embraced by 1990s’ indie fans as much as dance music lovers, and gave the band a direction that would lead to 1996’s equally gamechanging Second Toughest in the Infants, and a huge No 2 hit, Born Slippy (.NUXX) – made famous by its use in Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting. This is particularly remarkable, given Dubnobass... was Smith and Hyde’s third album as Underworld, and their fifth together in total (they spent the 80s in post-punk singles band Screen Gemz, then the extravagantly coiffeured, stadium-rock band Freur, changing their name, but not their sound, for two unremembered LP releases).

But Dubnobasswithmyheadman brought a revolution in mind, as well as sound: it was the first album Underworld had wanted to make rather than one they felt they had to make to satisfy the record industry. And rediscovering it lit the touchpaper for the album we are here to discuss: the joyously alive Barbara, Barbara, We Face A Shining Future, an album with a title as peculiar and wonderful as all the others before it, which arrives this month full of heart, soul and brilliant noise. At its centre are two men who found they needed each other after all.

“I’ve worked with some really terrific people who take you somewhere really, really good, but it doesn’t come close to this,” Hyde tells me.

“I’ve never heard you talking like this,” Smith replies, the Welsh vowels of his Amman valley childhood lilting and rolling. “It’s quite interesting how it works, us two, because we’re polar opposites, really. People ask us why we’ve been together so long, and it’s certainly not because we’re all loved up all the time.” He peers through his spectacles comically. “That’s not to imply that we’re constantly disagreeing, either. We’re just different, you know? But we’ve finally realised, at our tender age, that that’s OK.”

Three days before we meet in their rural Essex idyll, Underworld are in Bristol, kicking off their new album campaign with a televised headline slot at Colston Hall for the 6 Music Festival. In two weeks they will perform a rooftop gig in Japan and a spot on the country’s equivalent of Top of the Pops, on which only a handful of western artists have played, including Madonna and Metallica. Then comes a European tour and a summer of festivals, including Coachella and the headline slot at the new Festival of House in Angus, Scotland: an intimidating schedule for anyone, and the tension is building today.

Hyde’s voice is playing up for starters. “I’ve had a Throat Coat and a Strepsil,” he tells me, quietly, by way of introduction. Smith seems more anxious, but there is an extra reason for that. “If we don’t win, there’ll be trouble,” he burrs: Wales play Scotland in the Six Nations before the gig. (They win – his relief is palpable.)

Tonight the band will debut five new songs live, beginning the set with drum-driven new single, I Exhale, its lyrics, in trademark Hyde style, like evocative lost lines from short stories (“Spangled top/ Leather jacket/ Run your fingers through your hair/ We’re nearly there”). It arrived in January with a video that summoned up the spirit of Talking Heads’ Stop Making Sense, Hyde larking about in a suit, dancing and slamming doors. Next comes the slow-building If Rah, which bursts into a classic arms-in-the-air Underworld riff in the middle; the doomier Low Burn comes later, ending with the words “be bold, be beautiful, free, totally, unlimited”, as do the softer strains of Ova Nova and Nylon Strung.

Hyde and Smith first met in Cardiff in 1981. The Worcester-born Hyde was a student at the city’s school of art, working under progressive artist and educator John Gingell (“I made a hut and I hid in it but they weren’t very happy when I tried to burn it,” he explains). Smith had fled a bank clerk job in Llanelli to do an electronic and electrical engineering degree, and was handy at fixing amps; he dropped out during his finals after being asked to join Hyde’s band. “[Screen Gemz] were the biggest band in Cardiff for a month, which felt very exciting,” he says. “A month later they weren’t. And suddenly everything was all, oh shit.”

And so would the rest of the decade continue. Their second band, Freur’s, biggest success was the 1983 Talk Talk-like single, Doot Doot, (it got to No 59), while Underworld Mk I were signed to Sire by Madonna’s mentor Seymour Stein, and had minor hits in the US and Australia. Videos from that time exist on YouTube, and Hyde’s odd charisma is already present in spades, although it’s generally dampened by terrible haircuts, bad wardrobe choices and banks of screeching guitars.

The following sounds like a convenient myth, but it’s true: in 1990 Smith’s total income was £120, and his wife, Tracy, convinced him to change tack and make music he liked. “The best thing that ever happened to me,” Smith says. Interested in techno, he started working with young DJ Darren Emerson, and his world turned around. Hyde went along with him: “After 10 years of being conscious of what’s in the charts, what the record labels want, what we think we should be doing, which people didn’t get anyway, the minute our music got honest and personal, it became open to people.”

At 9.45pm a white word hums out of a black screen behind the mixing desk at Colston Hall: Underworld. A hall full of bodies, many in their 30s and 40s but plenty noticeably younger, starts to move. The unstarry set-up shouldn’t work. Underworld’s extra member in live shows, Darren Price, adjusts his headphones and fiddles with a laptop. Hyde wears his customary Breton top and jeans, and wiggles his legs around daftly. Smith is in the lumberjack shirt he’s been in all day, his grey hair shining under the lights, counting in Hyde before uncooly smacking an imaginary hi-hat.

Then the beat drops. It never leaves. The new songs fit into the set as seamlessly as though they’d been there for ever. Smith says in the dressing room later that Underworld’s never been about two people. “It’s about all those people.”

Later, back at the pig sheds in Essex, Underworld are talking about how exciting the early 90s really were, as their music started to shift and rock audiences started to mix with club crowds. “The energy was so fantastic, and the whole club culture at that time was so warm,” Smith begins. “It was significant to us that you could go out and feel safe. It wasn’t beered up, coked up, let’s have a scrap: people were going out to dance and enjoy themselves.”

They’re also passionate about how the innovative spirit of illegal raves fed into legal festivals with a similar ethos. In 1992 Underworld started doing their Experimental Sound Field events at Glastonbury, for example: they would play from a tower in the middle of a field accompanied by three speakers and a projector screen. The area would later become Lost Vagueness. “The spirit back then was all ‘Let’s make an event and put it on somewhere inspiring,’” says Hyde. “Like Michael Eavis giving us a field to play in for 18 hours!”

Hyde still loves festivals held in inspiring locations, like Japan’s Fuji Rock, held in an out-of-season ski resort by the Naeba volcano, or ones that have hidden stages and events.

“Spontaneity’s such an important part of that festival experience, but you can find it on the outer stages, with theatre, literature, film, other events. Saying that…” He laughs at himself. “I’m also glad that festivals have better food and decent toilets. I still remember seeing the Woodstock mud slides on TV as a kid and thinking, ‘Arrrrgggh! Who would do that?’”

When asked what day they’re playing Glastonbury this year, he laughs. “Let’s just say we’re playing lots of festivals that haven’t been announced yet. We’re leaving home and not coming back for a while.”

At Britpop’s high point, Underworld were also the hit of 1996’s Reading festival, when crowds fled the Stone Roses’s legendarily disastrous headline slot on the main stage for the thrills of Underworld’s set on the NME stage. It was a night, in Hyde’s words, that felt like “the passing of something and the coming of something else”. He finds it troubling that those times are being rewritten as being dominated by Britpop, and mentions a recent BBC documentary, “which was a very convenient history. I know the guy presenting it, and I was thinking ‘Oh, come on, man, you know that wasn’t the case, so what’s going on here, then?’ Massive Attack and Portishead were huge too. It’s a bit like 1984, almost.”

Underworld could be easily squashed into the Britpop narrative, however, partly because Hyde was hugely inspired by the working-class boys and girls of Romford, where he and Smith lived, but also because of the legacy of Born Slippy. “To some people, I’m just that shouty bloke,” Hyde says, smiling. The chorus line – “Lager, lager, lager, lager” – has been their albatross, in some ways. Hyde wrote it when he was battling alcoholism, and it’s a song inspired by how he saw the world on a particular night out in Soho. As Hyde told the Guardian in 2006: “It was never meant to be a drinking anthem; it was a cry for help.”

Still, it’s the song that made them secure, and they love playing it – they still close shows with it. Hyde was sober by the late 1990s. Underworld’s follow-ups to Second Toughest in the Infants – 1999’s Beaucoup Fish, 2002’s A Hundred Days Off (their first without Darren Emerson) and 2007’s Oblivion With Bells – still thrilled, as did long tracks they released online as part of their Riverrun project, in which they put music out almost as soon as they made it.

Sobriety also coincided with Hyde writing an online diary every day, with photographs (these are coming out as a book later this year, I Am Dogboy: The Underworld Diaries, published by Faber). It revolutionised his writing. He explains: “I remember Rick saying once, ‘Look at that, you’ve focused on an object, you’ve focused on something, use the same mentality, the same kind of way of looking at the world.’”

“Don’t think about stories or sentence structures, things that could be in a form that could be edited down,” Smith explains further. “I said to Karl, ‘When you try to make sense, it doesn’t make me feel the same way. When you just are who you are, then that makes me feel something.’”

Another phrase has helped Smith’s approach to his art in recent years. It came from Mark Rylance, the original narrator at the 2012 Olympic opening ceremony, Isles of Wonder (Kenneth Branagh stepped in when Rylance’s stepdaughter died three weeks before the event). As musical director of the production, Smith was in charge of soundtracking, and cueing in performers through their earpieces. “And I remember Mark saying to all of them when we were rehearsing, ‘You are enough.’ And I was suddenly, wow, oh, my god! He meant you can be taught by who you want, you can think what you want, but you are enough. Don’t worry. You can do this.” Smith nods. “We took that on.”

On the night itself, Smith was so emotional, he couldn’t physically go out and talk to the performers before the show. “I’d already got into a state where I was beginning to blub, quite literally, in certain situations. I thought, ‘I can’t break down in front of them, just as they’re about to go out and do this terrifying thing!’ I just went [through the ear pieces] ‘All right you lot? I haven’t got time to sing today. Left, right, come on, one, two, three, there you go, now!’”

Later, his work done, he stood with his family at the moment David Bowie’s Heroes blared out across the stadium. Hearing that song in that place reminded him of the alchemical power music has. “What an extraordinary musician Bowie was. He didn’t just give up or turn over. Music was still what he wanted to do when he was older, and for me, what a tremendous encouragement that is. Music really is magic, you know? That lyric for Heroes was nothing to do with the Olympics at all, nothing to do with anything patriotic: it was just music and half-understood words, and the power of that has always fascinated me.”

Does that way of working chime with Underworld too? “Yes, that’s what it’s like, working with Karl. It doesn’t matter where something comes from. It’s how it connects. It’s how it feels.”

When Smith and Hyde reconvened to make another record in late 2014, they decided to just do something new in the studio every day. Smith had a deadline in his mind; Hyde, conversely, didn’t have anything in mind. “For me, this wasn’t an album. Rick’s job is to make an album. That’s not my role. My role is to turn up and to be something else – the poet, philosopher, bullshit artist.” The pair laugh.

In the past, Hyde had also wrestled with the baggage of who Underworld were, what they meant. “The idea of being in a band, no matter how much I tried, it was always in my head [before]. This time, the last thing I thought about was Underworld, and weirdly, that made things work.” The album was made in less than a year; the quickest one they’d ever made.

It’s clear Barbara, Barbara, We Face a Shining Future felt right in every way, right down to the elliptical, tantalising title. Smith explains that the title is a phrase his father spoke to his mother not long before he died. “They had 62 years together and come on, you know. Those words reminded me of what you’re trying to teach your kids, that shit is going to happen,” – he smiles – “but go on, forward, face up, it’s going to be good.”

Smith turns to Hyde, and you feel the sun stretching out. “That title stuck in the best kind of way because it really meant something, and it’ll mean things to other people. And when you talk about positivity… my goodness.” Two men in their late 50s smile at each other. “To recognise that at that moment. We make our lives as we want them.”

Barbara, Barbara, We Face A Shining Future is released on Friday on Caroline Distribution. Underworld headline the Festival of House, Angus, Scotland, 10-11 June

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion