Microsoft's third-quarter financial results were published yesterday, and they had many high points: cloud revenue is growing well (though we have some misgivings about how the numbers are reported), Windows outperformed the PC market, and Office 365 passed 100 million corporate seats. But there were a couple of significant black marks: Phone revenue has dropped to effectively zero, and Surface revenue was down sharply year on year, with a 26-percent drop in revenue.

The phone revenue is no big surprise: Microsoft has all but abandoned the market, and the last phones to sport a Microsoft logo—the Lumia 950 and 950 XL—are no longer sold. The company has been winding down its phone operation, writing off the entire value of the phone business it bought from Nokia and laying off thousands of former Nokia employees in the process.

But the story with Surface is more unsettling. In its analyst call, Microsoft ascribed the drop in Surface revenue to "product end-of-lifecycle dynamics," whatever that means. The company's 10Q filing used rather clearer language: Microsoft simply didn't sell as many Surface systems.

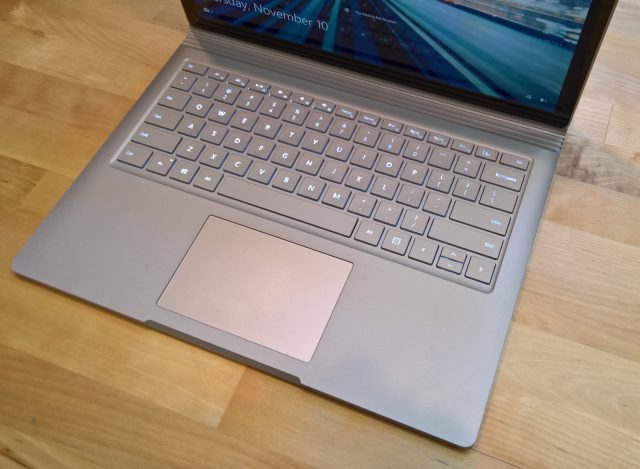

The Surface range has two main products: the Surface Pro 4, a tablet-style two-in-one, and the Surface Book, a laptop with a detachable screen. These systems were launched in November 2015. The Surface Pro 4 available today, about 18 months later, is unchanged. Surface Book has been slightly updated—a variant with a better GPU was added in November 2016. But it, too, is little altered.

These portable systems were joined late last year by the Surface Studio, a fascinating but flawed desktop system. With its high price—it starts at a dollar shy of three thousand bucks—and niche utility—it's compelling if you're in the market for a Wacom digitizer, but otherwise something of a curate's egg—Surface Studio is not designed to be a big seller with mainstream appeal. Microsoft didn't offer numbers, but we'd imagine that the majority of Surface sales are of the portables.

The march of technology

Eighteen months is a long time to wait for systems to be refreshed. The Pro 4 and Book were early adopters of Intel's Skylake processors, but Skylake is now a generation old. Kaby Lake, which started shipping last autumn, is not a huge advance over Skylake, but it's a more power-efficient design that offers meaningful improvements in battery life, improved encoding and decoding support for 4K video, and, for the low-power Y-series parts, meaningful improvements in performance.

Surface Pro 4 uses a Y-series part in the cheapest model, and it would stand to make big gains from a Kaby Lake upgrade. Microsoft wouldn't even have to do much work to make such a switch; Kaby Lake is pretty much a drop-in replacement for Skylake.

The last 18 months have also seen significant growth in the adoption of USB Type-C and Thunderbolt 3, which offer standardized single-cable charging and docking. While Thunderbolt 3 is still young, hardware companies are experimenting with concepts such as Thunderbolt 3 monitors that charge laptops over the same cable used to carry the display signal, external GPUs, and docking stations that are no longer specific to particular hardware models (or even OEMs). Indeed, it feels like a natural fit for a revised version of the existing Surface Dock, or even, dare we dream, a standalone version of the mouth-wateringly beautiful touch screen of the Surface Studio.

USB Type-C is rapidly gaining adoption; it has already become the norm for phone charging (for Android, at least) and increasingly is being favored for laptop charging. The slimline ports enable thinner PCs, and the ability to use a single port for power, USB connectivity, and video output is compelling.

No Surface product supports either technology. The Surface portable line-up, the bread and butter of the Surface brand, is looking very neglected.

At their release, the Pro 4 and Book were both arguably class-leading machines: 18 months later, they look sad and stale. Last November, we felt that we couldn't recommend the Surface Book's version with the updated GPU to most buyers—we couldn't justify buying a Skylake system with Nvidia 900-series graphics when the state of the art was Kaby Lake and 1000-series GPUs. Six months later, the machine looks even less appealing.

With this stagnation, falling sales are inevitable. Until Microsoft shows the brand some love, the decline will only continue. We're not expecting to see that love any time soon, either; the company's guidance for the current quarter is that Surface sales will continue to fall. Microsoft is holding an event next week, and we expect there to be some hardware element, but we've also heard from sources close to the matter that there won't be updates to the Surface Pro or Surface Book.

Either do hardware properly, or stop pretending

If Microsoft wants to make PC hardware, it needs to do so properly and commit to the same kinds of updates as other PC OEMs.

Almost every other PC OEM has refreshed its systems for Kaby Lake. Almost every other PC OEM has adopted, at least for machines in the premium space that Surface occupies, USB Type-C and Thunderbolt 3. Surface Pro—a machine which, in its early generations, arguably defined that particular style of two-in-one systems—is no longer unique. HP, Dell, Lenovo, Samsung, and others all have solid two-in-one offerings. These machines are modeled after the Surface Pro concept, but they now embody that concept better than Microsoft's own system. The Surface has been out-Surfaced.

The failure to do anything with Surface for so long makes us wonder just what Microsoft is up to. If the company is serious about its hardware ambitions—and officially, at least, it still says that its intent is to produce market-leading systems under the Surface brand—then it has to take its hardware seriously. That means refreshing it to keep pace with the competition.

One hardware company has a similarly lackadaisical approach to updating: Apple. In recent years, refreshes of Mac laptops and desktop systems across the lineup have slowed down. While the company has been quick to pick up Thunderbolt 3 and USB Type-C on at least some of its machines, the broader failure to keep pace with the state of the art is a continued source of frustration for Apple loyalists. But Apple's hardware sales remain robust, because Apple, in a very important way, is not like Microsoft or any other PC OEM: if you want to run macOS in a legal and supported way, you simply have no option but to buy Apple hardware.

There's no corresponding necessity when it comes to buying Surface. Microsoft is but one Windows OEM of many, and if Microsoft's hardware isn't offering the right feature mix, a system from HP or Dell or Lenovo or Samsung or some other company probably will. It's fine for Microsoft to take inspiration from Apple's close cooperation between hardware and software development; it's not fine for Microsoft to mimic Apple's unpredictable and inconsistent system refresh policies. The PC market dynamics don't allow it.

When Microsoft first started making hardware, there was widespread uncertainty as to what the company was hoping to do. General consensus was that Redmond's aim was to serve as a kind of trailblazer, building the kinds of systems that the company wanted to see in the world while pushing the PC market in the direction it wanted.

But this kind of hobby approach is a problem. Without assurances of a long-term commitment to hardware development, many would-be customers will avoid the systems. This is particularly acute in the corporate space: support lifecycles and extended system availability are essential when buying a fleet of systems. Microsoft recognized this concern and took action to address it. Surface systems were offered through the usual corporate channel partners like Ingram Micro and through cloud subscriptions, and the company promised that Surface Pro 3 peripherals would remain compatible with Surface Pro 4.

The message was clear: Microsoft wasn't merely dabbling in hardware, it was investing in building a serious hardware brand. After some early missteps, the hardware was solid and well-received, revenue grew steadily, and Surface looked like it was becoming an integral part of Microsoft's ecosystem.

That feels like it's now in jeopardy.

Troubling precedent

It doesn't help that Microsoft's hardware track record is more than a little shaky, and skepticism about its commitment and seriousness to hardware is well-earned. After a difficult start, Windows Phone was finally on an upward trajectory, especially in the EU where, in some countries, it had broken double-digit market share. But lackluster hardware—including a complete failure to offer a competitive new flagship phone in 2014—and lack of clear messaging saw a complete reversal of fortunes. The ultimate result was felt this quarter: Phone revenue is now essentially zero, even as work on the mobile version of Windows 10 continues.

Surface RT and Surface 2, Microsoft's ARM-based two-in-one machines, similarly raise questions about the company's commitment to hardware. Although Windows 10 itself has been built for ARM systems (and a version of Windows 10 for ARM is on the market in the Internet of Things guise), Microsoft opted not to offer a Windows 10 upgrade for Surface RT or Surface 2. This leaves the machines basically orphaned.

Microsoft's inaction has taken a promising prestige PC brand and turned it into a borderline embarrassment. The question of whether Microsoft cares about hardware and is in it for the long haul is once again a live one. We've seen similar levels of neglect before. It was ruinous for the Nokia phone business and devastating for Windows Phone. Windows on the desktop is, of course, going to prove more robust—it doesn't live and die on the fortunes of Surface in the way that Windows Phone hinged on Nokia and Lumia. But everything invested in building the Surface brand is now in doubt.

That's bad for anyone who likes the machines, including those corporate buyers who have made the leap to Microsoft hardware. It's even worse for the software company's future ambitions: later this year, we're going to see a new generation of ARM machines running Windows. But with the way the company has treated its other hardware endeavors, who would want to take the gamble? Microsoft has developed a habit of ignoring and abandoning its niche hardware platforms; what reason is there to believe that Windows 10 for ARM will be any different?

reader comments

295