The Class of 2010 Heads Home

Discouraged with Congress, some representatives elected in the Tea Party wave are leaving Washington after just three terms. Here are four of their stories.

There were 87 of them in all, the Republican men and women who remade the House of Representatives on November 2, 2010. They swept into office on the Tea Party wave; swept out the first woman speaker, Nancy Pelosi; and in a single day, halted the trajectory of Barack Obama’s presidency.

No longer would the president have a pair of Democratic majorities in Congress to usher through the remainder of the ambitious agenda he hadn’t completed in his first two years. There would be no congressional action to tackle climate change, to reform immigration laws, or to increase the minimum wage. Propelled by an achingly slow economic recovery and voter backlash against the Affordable Care Act, the Republicans elected in 2010 would be the largest class of newcomers to Congress in more than 60 years. They barreled into the Capitol promising to repeal the president’s new health law, to overhaul the tax code and entitlement programs, and to slash a federal deficit that had swelled to more than $1 trillion.

Yet six years later, many of those same Republicans are leaving, departing Washington right alongside the man they had come to fight. More than a dozen are leaving the House in 2016—four are giving up their seats to run for the Senate, and nine more are simply heading home.

Of the 87 Republicans who were sworn in as congressmen in January 2011, nearly one quarter are already gone. Some, like Tim Scott of South Carolina, Cory Gardner of Colorado, and James Lankford of Oklahoma, moved quickly up to the Senate. A few lost their reelection bids in 2012. Michael Grimm of New York is in prison, and Alan Nunnelee of Mississippi died of cancer.

Thanks to gerrymandered districts and all-consuming fundraising schedules, most members of the House can keep their seats for as long as they want them. More than a dozen retire every two years, part of the natural turnover of Congress. But as the Brookings Institution noted, the Republicans who are departing voluntarily this year are leaving much sooner than typical retiring lawmakers.

The GOP class of 2010 had plenty of career politicians—eager city council members, small-town mayors, and state legislators who were moving up the electoral ladder by running for the U.S. House. But the group was known for the many men and women who had never served in elective office before, those who left their jobs as farmers, car dealers, farmers, military officers, sheriffs, and radio hosts—even as a funeral director—to come to Washington. And by and large, these are the novice lawmakers who decided after just five years that they’ve had enough of Congress.

Here are the stories of four of them: Richard Hanna, who started his own construction business in upstate New York; Scott Rigell, a car dealer from Virginia; Reid Ribble, who ran his family’s roofing business in Wisconsin; and Rich Nugent, a veteran Florida sheriff. Each of them said they arrived in Congress with high expectations, hoping to right the fiscal ship and bring an outsider’s perspective to Washington. Like many first-time politicians, they imposed term limits on themselves—four terms in the case of Ribble and five or six for the others. But while many lawmakers ignore those campaign pledges and stay much longer than they promised, each of these four is doing the opposite: They’re returning home earlier than planned. Sure, they want to get back to their families, but each of them leaves, to varying degrees, discouraged if not downright saddened—at the snail's pace of progress in Congress, at a president who wouldn’t compromise, at a party that lurched too far to the right, or in one case, at all of those things.

“I guess we were all probably naïve, those of us that never served in the state legislature,” Nugent told me. “We were naïve to how you get things done, or how quickly or not quickly you can move things.”

Richard Hanna

By his own description, Richard Hanna is not flashy. “I’m a grind-away guy,” he says. And he’s certainly not the most outspoken member of the 2010 Republican class. Far from it.

Just don’t get him started on his disenchantment with the Republican Party, the 2016 presidential campaign, and Congress in general. In the course of a 30-minute interview, Hanna used the following words: “Embarrassing,” “ashamed,” “disappointed,” “uncomfortable,” “callous,” and “immoral.”

The 65-year-old owned a construction company in upstate New York before he decided to run for Congress. He figured he’d finally put the economics and political-science degree he earned decades ago in college to some use. “I woke up one day and said to my wife, ‘I think I’ll run for Congress,’” Hanna recalled. “And she said, ‘Shut up and go to sleep.’”

Hanna was never a Tea Party type; he’s a Northeast Republican in the Rockefeller tradition—fiscally conservative but more liberal on social issues, including abortion and same-sex marriage. He first ran in 2008 and lost before getting in during the 2010 wave, toppling Democrat Michael Arcuri in a district that had previously been held for more than two decades by a similarly-moderate Republican. He shared the idealism, if not the ideology, of many of the non-politicians in his class. “I think I came here and I thought, my goodness, I’m going to be among committed people with some degree of talents and a willingness to compromise and work through their problems,” Hanna said. It didn’t take long, however, for the frustration to set in. “I came from a practical, productive world, and I’ve been here five years now,” he said, “and I have been disappointed in our willingness to deal with some things directly that are critical. And in some ways, I just became discouraged with the lack of productivity.”

From a tax overhaul to immigration reform, Hanna watched as House Republican leaders failed to follow through on promises to tackle the biggest challenges, instead “voting against Obamacare 63 times where there are so many other things to do.” He became particularly distressed with the GOP’s handling of women’s issues. Attempts to add provisions excluding immigrants and Native Americans from the Violence Against Women Act, he said, were “immoral.” And when party leaders set out to target Planned Parenthood last year, Hanna wanted no part of it. “I didn’t come here to go after women’s healthcare,” he told me.

In October, Hanna caught flak for becoming the second House Republican—after Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy—to acknowledge there was a political motive to go after Hillary Clinton behind the GOP’s Benghazi Select Committee. But unlike the embattled majority leader, he defended his comments. “The vast majority of people have said to me, ‘You shouldn’t have said that,’” he said. “But almost no one has said I was wrong.”

Hanna said the blowback from his remarks played no role in his decision to retire this year instead of serving another couple of terms, as he originally planned. Nor, he said, did the prospect of facing a primary challenge from the right for a second straight election. What was a factor, he conceded, was the possibility that he’d have to run on the same Republican ticket as Donald Trump or Ted Cruz. “You want to be proud of the people that lead your party,” Hanna said. “You don’t want to feel ashamed or uncomfortable, and the language and tone and tenor is so mean-spirited and often just plain callous it’s hard to be a party to it.”

Ultimately, the frustration just grew to be too much, not only with the campaign but with the GOP as a whole. “I can’t be a party to a lot of what I see here, and my discomfort with our agenda has grown,” he explained. “I just decided it was time to go home.”

Scott Rigell

Scott Rigell remembers quite well why he first decided to run for Congress in the middle of 2009, and it was very similar to the rationales for many of the 87 Republicans who swept into office the following year: He wanted to wrest control of the House from the Democrats and stop President Obama’s heavy-spending agenda. “It was to take the gavel from then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi,” he told me. “It was very specific to me that I was trying to be part of flipping the House. It was a top-of-mind awareness to me, and it’s what got me up at 5 or 6 every morning for 17 months seeking the office.”

Rigell, 55, owned car dealerships in southeast Virginia. He had been involved in politics as a Republican donor, but he had never run for or held public office before. Rigell initially balked when a former House member from the area, Thelma Drake, urged him to challenge Representative Glenn Nye, a Democrat. His business was having too much trouble, he said, and the auto industry was “imploding.” About a week later, however, he attended a fundraiser for Bob McDonnell, then a rising Republican star running for governor. Mike Huckabee, fresh off his 2008 presidential run, was the key speaker. Rigell says he remembers Huckabee’s words almost verbatim. “Are you unhappy with your own party?” the ex-Arkansas governor asked the crowd. Rigell was. “Are you dissatisfied with the direction of your country?” Huckabee asked. Rigell was. “Then he said, ‘Well, our country is worth fighting for and sacrificing for,’” Rigell recalled. “It was a wave of emotion that hit me at that moment.”

Rigell talked to his wife, Teri. “I’ve got to know I was willing to do this,” he told her. And so he ran.

Although Rigell ran for many of the same reasons as his 2010 colleagues, he developed a maverick streak soon after arriving. As conservatives united against tax increases Obama demanded as part of any fiscal deal, Rigell publicly repudiated Grover Norquist and the activist’s anti-tax pledge that he signed during the campaign. He said he didn’t really understand it at the time, and he came to dispute Norquist’s arguments that the budget should be balanced with spending cuts alone. “I’ll debate Grover Norquist anywhere anytime on that matter,” Rigell said. In subsequent years, Rigell also made it a personal policy never to refer to the Affordable Care Act as Obamacare, an attempt to avoid denigrating the president out of respect for the many African American voters in his district.

Like several of his colleagues, Rigell complained about the many time-wasting procedural and political votes the House takes and the difficulty of getting things done. And under the term limits he imposed on himself in 2010, he could have run another three times before retiring. But he said his reason for leaving Congress was not so much frustration as it was a sense that he had accomplished what he set out to do. Republicans may not have repealed the healthcare law or overhauled entitlement programs, but if nothing else, the House GOP class of 2010 has succeeded in stymying Obama’s legislative agenda and reversing the trajectory of federal spending.

Rigell recalled a moment in a Republican conference meeting when the new House speaker, Paul Ryan, boasted that the GOP now had its largest majority since 1938. That’s why Rigell had run, to “flip the House.” Suddenly, he said, “here’s this exit ramp that’s coming into focus.” He said he debated for a while whether to retire now or to redouble his efforts to increase his influence in the House over the next few terms.

“I started calling up my wife Teri in Virginia Beach and saying, ‘Teri, I think I’m supposed to come home,’” Rigell said. “And she’d say, ‘I think you’re right.’”

Reid Ribble

It was the beginning of October, 2013. The government was shut down in a budget impasse over Obamacare, and Reid Ribble was part of a group of 10 lawmakers who had been negotiating secretly on what would have been a fiscal Hail Mary pass—a deal that would not only reopen the government but would set the nation on a path to shave trillions off the deficit over the next decade. The group spanned the political divide: five Democrats and five Republicans, including members of the Progressive Caucus, the conservative Republican Study Committee, and what would later become the hard-right House Freedom Caucus. Inside the room, the lawmakers had reached an ambitious agreement to save $5.2 trillion, more even than the Simpson-Bowles Commission or the “grand bargain” that Obama had tried to strike with then-Speaker John Boehner. Republicans were consenting to “revenue enhancements”—Beltway code for tax hikes—while Democrats had agreed to increase the retirement age and make changing to the way cost-of-living-adjustments to Social Security benefits are calculated.

Then it came time to go public with the deal, and the whole thing fell apart. Out of the 10 members in the room, just three would agree to put their names on the agreement, Ribble recalled. “It became a moot point,” he said.

For the small businessman from Wisconsin, that failure was an object lesson in political polarization and the courage it saps out of Congress. And it was exactly what people had warned him would happen when he arrived. “What I didn’t expect was that I would hear repeatedly, ‘Yeah you’re right. I agree with this. That’s what we’ve got to do, but I’m not going to sign legislation to do that,’” Ribble said. “Getting an agreement in private is no different as having no agreement at all.”

Ultimately, Ribble’s frustrations extend from the White House, where he criticizes Obama for a refusal to engage with Republicans, back to the Capitol, where he says the once-hallowed congressional committee process is in dire need of reform. The new speaker, Paul Ryan, is a fellow Badger and a close friend of Ribble’s who has vowed to re-empower committees and pursue a bolder agenda. Ryan urged Ribble to stay in the House for another two years, but Ribble said his family was calling him home. In particular, he talks about his 12-year-old grandson, who was just seven when Ribble first ran. As Ribble prepared to return to D.C. from this past winter break, the 12-year-old broke down in tears at the airport. “It was a bit of a gut-check moment. It’s not like he was a 4-year-old telling me this. He’s 12,” Ribble explained. “My family was pretty emphatic that now was the right time.”

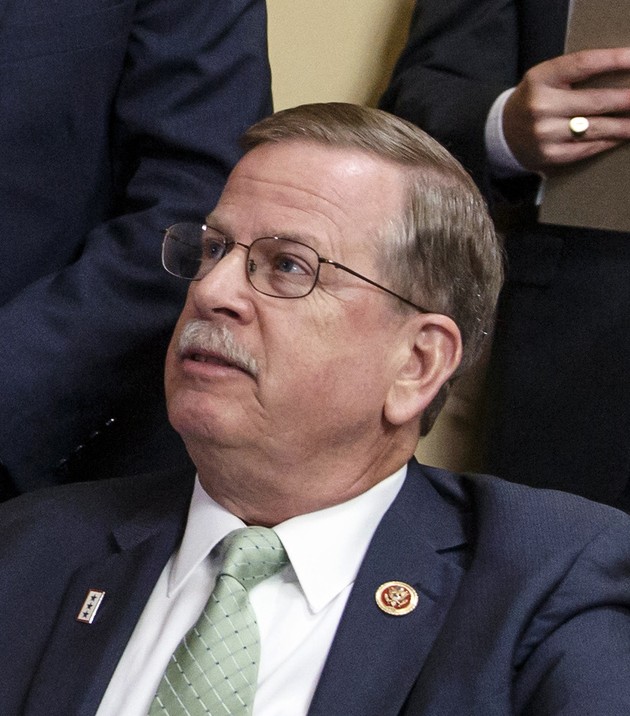

Rich Nugent

“I found that I probably wasn’t designed to be a legislator,” Rich Nugent told me toward the end of a half-hour interview. Unlike the three other Republicans I spoke to, Nugent had actually run for, and won, elective office several times before he arrived in Congress five years ago. But those were all for sheriff in Hernando County, on the west coast of Florida. And that was a role that suited him. “You could identify a problem, you staffed the problem, you came up with a solution, and you’d implement it,” Nugent said. “Here obviously you don’t have that kind of control or input.”

A case in point was Nugent’s top legislative priority: a bill he authored to improve mental-health treatment in the criminal-justice system, particularly for veterans. But by the beginning of his second year in the House, he realized that he had no chance of advancing the bill because he wasn’t on the right committee, and he didn't have the seniority or the political savvy to muscle it through. After years of trying, he finally deferred to a colleague on the House Judiciary Committee, who might actually get the legislation signed into law—and will surely get the credit for it if he does. “That’s frustrating,” Nugent conceded. “It was like, ‘Ok. I get it now.’ And I don’t play that game very well. There are some folks that do it very well. I don’t. I know my limitations.”

As far as influence with the party leadership, Nugent’s fate was sealed a year ago, when he shocked his colleagues and family alike by voting against Speaker John Boehner’s reelection on the floor of the House. Nugent had certainly been a conservative member, even joining the Tea Party Caucus when it formed, but he was not a rabble-rouser or a vocal Boehner critic. He decided on his vote the night before, after discussing his problems with the speaker about his management of the House and coming away disappointed. Nugent was one of 25 Republicans who voted against Boehner, but because he was one of only two who served on the Rules Committee—a panel known as “the speaker’s committee” because of its requirement of loyalty—he was quickly punished along with a fellow Floridian, Daniel Webster. A staffer told him not to show up to the committee’s meeting that evening.

“I knew absolutely that I would be removed from that committee just because it was the ‘speaker’s committee,’ Nugent said. “But at some point in time you’ve got to stand up and say, ‘Hey listen.’” He said he knew Boehner had no choice but to boot him, and that he actually respected the speaker for doing it.

Assessing the record of the GOP class of 2010, Nugent said its members accomplished more than they’re given credit for. While the president has claimed credit for bringing down the deficit over the past few years, he pointed out that Republicans in Congress were the ones forcing the spending restraint. At the same time, he said, there was disappointment. “Obviously, I had higher expectations,” Nugent said.

When Nugent ran for Congress, he told his constituents he would serve a maximum of 10 years, or five terms. He’s leaving after three. “I didn’t make it,” he said.