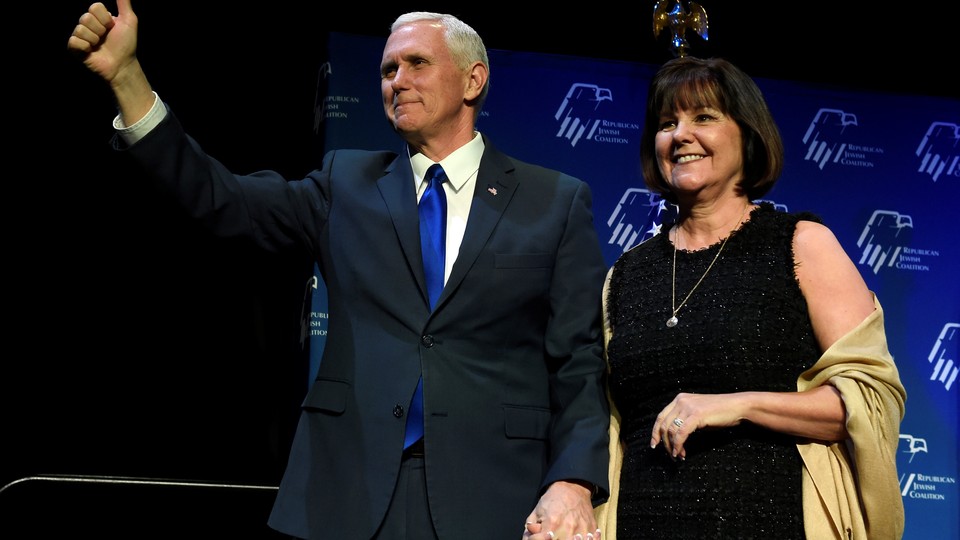

How Mike Pence's Marriage Became Fodder for the Culture Wars

Outrage over the vice president's approach to marriage reveals how deeply gender divides American culture.

The Washington Post ran a profile of Karen Pence, the wife of Vice President Mike Pence, on Wednesday. The piece talks about the closeness of the Pences’ relationship, and cites something Pence told The Hill in 2002: Unless his wife is there, he never eats alone with another woman or attends an event where alcohol is being served. (It’s unclear whether, 15 years later, this remains Pence’s practice.) It’s not in the Post piece, but here’s the original quote from 2002: “‘If there's alcohol being served and people are being loose, I want to have the best-looking brunette in the room standing next to me,’ Pence said.”

Some folks—mostly journalists and entertainers on Twitter—have reacted with surprise, anger, and sarcasm to the Pence family rule. Socially liberal or non-religious people may see Pence’s practice as misogynistic or bizarre. For a lot of conservative religious people, though, this set-up probably sounds normal, or even wise. The dust-up shows how radically notions of gender divide American culture.

Pence is not the first contemporary public figure to set these kinds of boundaries around his marriage. He seems to be following a version of the so-called Billy Graham rule, named for the famous evangelist who established similar guidelines for the pastors working in his ministry. In his autobiography, Graham notes that he and his colleagues worried about the temptations of sexual immorality that come from long days on the road and a lot of time away from family. They resolved to “avoid any situation that would even have the appearance of compromise or suspicion.” From that day on, Graham said, he “did not travel, meet, or eat alone with a woman other than my wife.” It was a way of following Paul’s advice to Timothy in the Bible, Graham wrote: to “flee … youthful lusts.”

The Hill article gives more context on how the Pences were thinking about this, at least back in 2002. Pence told the paper he often refused dinner or cocktail invitations from male colleagues, too: “It’s about building a zone around your marriage,” he said. “I don’t think it’s a predatory town, but I think you can inadvertently send the wrong message by being in [certain] situations.”

The 2002 article notes that Pence arrived in Congress a half decade after the 1994 “Republican revolution,” when Newt Gingrich was the speaker of the House. Several congressional marriages, including Gingrich’s, encountered difficulty that year. Pence seemed wary of this. “I’ve lost more elections than I’ve won,” he said. “I’ve seen friends lose their families. I’d rather lose an election.” He even said he gets fingers wagged in his face by concerned Indianans. “Little old ladies come and say, ‘Honey, whatever you need to do, keep your family together,’” he told The Hill.

These comments show that the Pences have a distinctively conservative approach toward family, sex, and gender. This is by no means the way that all Christians, or even all evangelical Christians like the Pences, navigate married life. But traditional religious people from other backgrounds may practice something similar. Many Orthodox Jews follow the laws of yichud, which prohibit unmarried men and women from being alone in a closed room together. Some Muslim men and women also refuse to be together alone if they’re not married. These practices all have different histories and origins, but they’re rooted in the same belief: The sanctity of marriage should be protected, and sexual immorality should be guarded against at all costs.

That idea might seem disorienting to more socially progressive Americans. For one thing, it shows a deep awareness of gender and sexuality: The implication is that temptations to flirt or cheat are present in everyday interactions.

Some journalists on Twitter quickly pointed out that Pence’s rules may function, in practice, to perpetuate professional and political disadvantages against women. If men in power can meet alone with other men but not women, they’ll just keep doing the business of being powerful in an all-male world. And it parallels critiques of the Billy Graham Rule that’ve been leveled within the evangelical community, as well, where it’s also been blamed for subjecting professional relationships to the logic of a sexually permissive society.

Other critics connected these views to Pence’s stance on LGBT issues. When he was governor of Indiana, he presided over a controversial religious-freedom bill that, LGBT advocates claimed, would have allowed business owners to discriminate against them. Pence’s marriage rules implicitly suggest there’s a temptation in being alone with women, but not in being alone with men, which is not the experience of a lot of people, including LGBT Christians.

But it’s also true that these aren’t just rules by, for, and about Mike Pence. This is how he and his wife, together, have chosen to navigate their marriage. That some people are so quick to be angered—and others are totally unsurprised—shows how divided America has become about the fundamental claim embedded in the Pence family rule: that understandings of gender should guide the boundaries around people’s everyday interactions, and protecting a marriage should take precedence over all else, even if the way of doing it seems strange to some, and imposes costs on others.