Moral Injury

Moral Injury: How Collective Injustice Harms Us All

The distressing onslaught on our sensibilities remains unabated.

Posted April 3, 2017 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

When social trust is destroyed, it is replaced with the settled expectancy of harm, exploitation, and humiliation from others. —Jonathan Shay

Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations. —Lutz et al., 2009

[Moral injury is a] disruption in an individual’s sense of personal morality and capacity to behave in a just manner. —Drescher et al., 2011

What is "moral injury"?

"Moral injury" (Shay, 2014) is a term used by psychiatrist Jonathan Shay to describe how warriors faced with committing or witnessing morally problematic acts in the course of duty suffer harm related to conflict with their values. This may happen because of orders from above, as a matter of personal decision, or both.

I'm going to review the concept of moral injury and discuss "collective moral injury" — a speculation about the effect of ongoing, unrelenting moral injury on the body politic. To a large extent, in spite of being vocal on social media, we are often passive witnesses to what is going on. For example, if you are a human rights supporter, moral bruising may be a daily occurrence.

While moral injury has mainly been used to discuss reactions to combat not covered under PTSD, the concept has broader applications. Doctors, human rights workers, humanitarian workers, first responders, therapists, survivors (of abuse, of political violence, of torture, of forced migration) and so on are regularly confronted with terrible moral situations in addition to direct and indirect stress.

Less dramatic than the extremes, we confront ordinary moral and ethical dilemmas every day. Walking past a homeless person, perhaps, and wanting to help but deciding not to... having a friend whose child is having problems, but not saying anything, for example.

Avoidance is a decent short-term strategy when we feel or actually have less control, but over a longer period it can become chronic emotional numbing, decreasing empathy and the ability to be open with others. I suspect moral numbing, if you will, can lead to a state of dehumanization, with ill-effects for all. Demoralization can be an adaptive response but can lead to burnout and other problems.

Exposure to stress is also thought to lead to post-traumatic growth (Westphal & Bonanno, 2007), or growth following adversity. Moral strain can provoke positive reactions, leading to greater motivation to seek change, and moral, spiritual and emotional development. This appears to be more likely if one experiences guilt, rather than shame, as discussed below. Adaptive self-deception, and attitudes such as belief in a just world, are thought to be associated with better outcomes during stressful circumstances.

Why collective moral injury is routine

What happens when shared moral dilemmas stimulate us daily, and it just isn't possible to get used to it or ignore it completely? Given Trump's attention-grabbing style and disruptive, seemingly capricious approach, it's easy to be knocked off balance by the constant emotional roller-coaster, not to mention all the threatening possibilities always on the table. In the news, social media, blogs, in casual personal and professional discussions... if it isn't explicit, it's still in the air all the time, unspoken, a hairsbreadth away from awareness. In addition to causing stress from threat, the state of the world is a constant moral strain. It is visible in protests rife with moral outrage, glaring injustice, racist and fascist fervor, general divisiveness, and the distortion of fact for fiction which only serves to increase uncertainty and undermine trust and safety.

There are, of course, struggles taking place around the globe constantly. As you are reading this, people are committing genocide, refugees suffer in numbers previously unheard of, consequences of lost healthcare coverage loom, glaring social and economic inequality lead not just to disparities in opportunity but ruined lives and violence, corporate greed and favoritism trump fairness, constant disasters and terrorism take place, climate change escalates, and there is a general decay of basic human decency.

Are there clear indications that our leaders are dropping the ball, creating betray of basic rights? Betrayal by leaders is a feature of moral injury highlighted by Jonathan Shay (below). Are our leaders failing to maintain a society that provides structure, safety and trust? Is this a violation of a solemn promise, a social compact between government and the people?

In America, for years now, there has been partisan fighting and nepotistic agendas crippling our representative political system. Our system, meant to limit the damage done by incompetent or malicious leaders, is being tested from within, by questionable leadership by Trump and and his administration, satirical often comedic characterizations of same, and infighting within both parties in addition to their inability to collaborate. Our system is being tested from outside by the specter of interfering foreign governments, most notably from alleged election manipulation by, and disturbing ties with, Russia.

How has conceptualizing PTSD paved the way for social change?

Of course, it is easy to see how all of these factors are collectively traumatizing. Over the past four decades, our culture has become intimately familiar with trauma. As with moral injury, post-traumatic stress disorder was first recognized out of necessity following the Vietnam war, but not until much preventable harm (a moral transgression) had been perpetrated. Before PTSD was introduced as a diagnostic category in 1973, such negative effects of combat were poorly understood, and often interpreted as being a form of weakness, stigma and shame. Aside from terms like "fog of war," battle fatigue, and shell shock, a telling former term for PTSD was "Lack of Moral Fiber."

Once veterans' PTSD broke into the public conscious (and conscience), it was easier to see in other areas — rape and domestic violence, traumatic events like illness, death and accidents, child abuse, torture and human rights violations, natural and man-made disasters and terrorism, secondary traumatic stress reactions, developmental trauma ("complex PTSD"), racism, gender inequality and related bias, homicide and other forms of perpetrated violence, and so on.

Conceptualizing traumatic stress opened the door for addressing suffering which had previously been brushed under the rug. This paved the way for recognition, repair and prevention... though we have only scratched the surface in spite of great progress. War always has a trickle-down effect, in every basic sphere of human life.

Is moral injury following in the footsteps of PTSD?

Will the moral injury take a parallel path to PTSD and raise awareness of moral injury in other spheres? Should moral injury follow suit? Will we survive if we fail to appreciate the widespread role of moral injury, and the damage done by avoiding dealing with the causes of collective moral injury? Easy to see that these issues have been present for all of human history. While violence and death is overall declining across recorded human history, the stakes of losing control are higher than ever before due to the destructive capacity unleashed by technological advancement, which counterbalances the promise of the same advances.

Human destructive instincts, aggression, competition, are balanced out by innate moral instincts, social, religious and political institutions, to keep extinction in check. What has changed recently is the already noted constant bombardment with information and, crucially, the spread of belief in basic human rights. Following WWII and the Holocaust, Eleanor Roosevelt in 1948 led the charge for the UN to create the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; an important step forward in raising awareness and establishing moral standards. Recognizing moral transgression is required for moral injury (see below), as well as for moral repair.

Nowadays, many folks I know are in a state of continual moral injury, as well as persistent traumatic distress. Of course, I am in a skewed sample because the majority of my friends and colleagues are striving to offer help to others on individual and collective levels, and because I live in a liberal, progressive city and mainly move in politically progressive circles.

I also know folks who don't share my particular views, but they may share a similar sense of moral injury. It may be organized around a different set of moral beliefs but the sense of indignation is familiar. Obviously, this doesn't do much to build bridges, unfortunately.

A detailed discussion of moral injury

In his original use of the term, Shay discussed what happens when leaders place warriors in morally tenuous circumstances. He notes three steps in moral injury in his formulation:

- "A betrayal of what's right"

- "By someone who holds legitimate authority (e.g. a military leader)"

- "In a high stakes situation"

By contrast, Lutz et al. (2009) describe moral injury from a different perspective, emphasizing the personal impact of the soldier making a difficult decision, one which is:

- An act of transgression "that severely and abruptly contradicts" a person's expectations about moral conduct

- The person "must be (or become) aware of the discrepancy between his or her morals and the experience

- Which "causes cognitive dissonance and inner conflict"

Regardless of whether the moral injury arises from leadership or oneself, moral injury may happen when we either witness or directly participate in immoral acts (potentially including hearing accounts of moral violations), when we do not prevent moral transgressions from taking place, and when we experience reactions which we find inappropriate in response to a moral transgression.

Drescher et al. (2011) conducted a preliminary research survey to see if the concept of moral injury was considered an appropriate and useful addition. Is the concept of moral injury considered valid? Is it necessary to have an additional concept, or is the prevailing construct of PTSD sufficient?

They interviewed 23 healthcare and religious professionals with long experience working with the miltary. They found unanimous agreement that the concept of moral injury is needed, and that the concept of PTSD was insufficient to capture the full scope of combat-related issues. Participants suggested changes to improve the existing working definition and language use currently in place in the moral injury literature. Regardless, whether traumatic or morally injuries, destructive events of human origin — as contrasted with natural events — have a greater negative impact.

In illustrating moral injury, Shay shares the story of a sniper in a recent war. The sniper is there to protect his fellow Marines, who are being picked off by an enemy sniper. He sights the enemy sniper, and finds that the sniper has a baby in a sling, possibly as a human shield. According to the accepted rules of war, he is directed to take the shot, knowing he will be killing both the man and the baby. He does, and sees the bullet find its mark.

From the point of view of moral betrayal from leadership, the soldier has been placed in a position by his command which puts him in a position where he must take action which violates his moral code not to kill civilians, moreover not to kill children. Yet the rules of engagement, which he is obligated to follow, tell him he must kill the sniper regardless, in order to protect his fellow soldiers (which is also morally correct). From the point of view of individual autonomy, the soldier has a choice: he can take the shot and violate the moral code of not killing innocents, or he can fail to take the shot, and violate the moral code of protecting his brothers in arms.

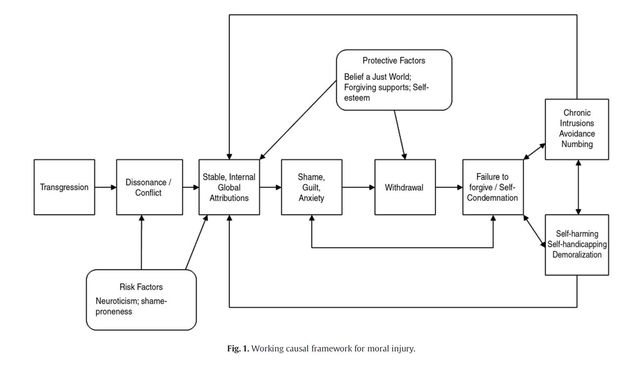

Regardless, moral injury can take over when the affected individual experiences it as global, interally-generated, and stable over time, leading to powerfully destructive feelings of shame. Interestingly, Litz et al. note that unlike shame, guilt tends to be more useful, associated with less self-punishment and more likely to move us toward taking positive steps to address whatever it is we feel guilty about. Guilt tends to mobilize us to act, whereas shame is more likely to lead to inaction and concealment.

In the absence of support and repair, shame leads self-imposed isolation, further increasing feelings of shame. Protective factors include belief in a just world, forgiving supports, and good self-esteem, while risk factors include a neurotic personality style and bias toward shaming oneself. The cycle looks like this:

Moral injury and PTSD fit well together

Notably, moral injury, while sharing some features of PTSD, differs in many important ways. First, moral injury is not considered pathological, but a normal human response to moral transgression. Second, the core cause of traumatic reactions relates to fear, horror and hopelessness, while with moral injury the core emotions are guilt, shame and anger. They share the tendency to relive the event and to want to avoid thinking about it, but while PTSD is characterized by over-activation of the nervous system, moral injury is not. While the primary concern in PTSD is safety, the primary concern in moral injury is trust. It is easy to see how they are complementary in understanding human responses to man-made distressing events.

Parting thoughts

Taken together, collective trauma and collective moral injury present a challenge for our species. On a broad societal level, the damage is self-inflicted. It is unclear how much of this is by choice, whether out of evil, human nature, calculated ethical decisions weighing difficult risks and benefits, or from unconscious factors which elude collective repair. We may be at a crossroads — can we come together, fulfilling the vision of universal human rights, or will we continue to inch closer to the precipice? Do we need to move the doomsday clock closer and closer to midnight in order for sanity to kick in, or are we a lost cause?

Having an orientation toward compassion and human rights can help but the adoption of such philosophies across many cultural and religious groups happens at the proverbial snail's pace. Moving in that direction doesn't address the issues which come up in the meantime, when some are not on the same page, and aren't playing by those rules (even when they say they are). One person's moral outrage may be another person's moral rectitude. This leads to a justification for aggression out of necessity, inevitably perpetuating the cycle. We can't place all the responsibility on our leaders. Getting up to date information is useful, but right now it's hard to tell what is actually happening, though strong opinions abound. It's a good idea to stay as resilient as possible.

References

Lutz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, Lebowitz L, Nash WP, Silva C, Maguen S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review 29, 695-706.

Drescher K, Foy DW, Kelly C, Leshner A, Schutz K, Litz B. (2011). An exploration of the viability and usefulness of the construct of moral injury in war veterans. Traumatology 17(1) 8-13.

Shay J. (2014). Moral Injury. Psychoanalytic Psychology. Vol. 31, No. 2, 182-191.

Westphal M & Bonanno G, (2017). Posttraumatic growth and resilience to trauma: different sides of the same coin or different coins? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 56(3), 417-427.