A year after the EU deal with Turkey to stem the flow of migrants into Europe, Hungary is doubling down protection of its border.Syrian refugee family at the Kelebija transit camp, March 23,2017.Krystian Maj/Press Association. All rights reserved.

The western gaze needs fresh victims and apparently it sees in me one of those new victims. How do I know this? I read it in the newspaper, in the Wall Street Journal, no less. Here is what the WSJ said about me on August 24, 2016:

In Istanbul, Nil Mutluer grabbed her 3-year-old daughter and raced with a suitcase toward Turkey’s coast. The former sociology-department chair at the city’s Nisantasi University narrowly escaped the nation’s looming dragnet. “Authorities had already begun questioning colleagues at the airports,” said Dr. Mutluer, a Western-leaning liberal who took a ferry to Greece en route to an academic post in Berlin.

A striking beginning for a newspaper story isn't it? An academic single mother escapes with only one suitcase and her three years old daughter, via Greece to boot! Touching too – exactly the sort of human interest story of victimisation that the western gaze seems to demand from its news outlets.

A couple of months after that story was published, the Turkish correspondent of another major European news outlet, herself a Turkish citizen, contacted me. Having finally discovered what has been happening to Academics for Peace since the beginning of the year, she told me that she had interviewed a number of other academics who had left Turkey and that she would like to include my story in her article as well.

I agreed on one condition. I asked her to keep my visit to Greece before coming to Germany out of her article – not because it was something that I particularly wanted to hide, but because I thought that it was irrelevant. The only possible relevance was that Syrian refugees also sought to reach Europe via Greece, but though politically persecuted in Turkey, I was and am not a refugee and that was not the reason why I chose to make a stop in Greece, before going to Germany. "But going to Europe via Greece is what makes your story different from the others" she protested. "But it is irrelevant" I protested back. In the end, her article was published and, thanks to my adamant refusal, this time my story was not in it.

Yes, the western gaze needs new victims, but am I that victim? Well, I am a 'scholar at risk', that much is true enough. Although I have been active in various feminist and human rights circles and have been working on issues regarding democratization for almost two decades, I have officially gained that status thanks to one modest political act in a whole lifetime: I joined over a thousand other colleagues – Academics for Peace – in signing a peace petition, "We will not be a Party to This Crime", which called on the Turkish state to cease its accelerating violence in the Kurdish provinces and respect domestic and international laws.

Our action was peaceful, but President Erdogan's response to it was disproportionately heavy-handed. In no less than five public speeches targeting us, he accused us of making terrorist propaganda and betraying the country. Taking their clue from Erdogan's speeches, pro-governmental newspapers published our photos and our names without bothering to disguise their threats of vengeance for what they considered to be an 'act of treason' on our part. One ultra-nationalist mafia leader voiced his desire to take a shower in our blood. Public prosecutors started criminal investigations against all the signatories of the petition, and four of our friends, who were unfortunate enough to read at a press-conference a joint press-release expressing our commitment to demanding peace, had to spend more than a month in pre-trial detention.

The governmental regulatory body of higher education in Turkey, the so-called Higher Education Council pushed the universities to open disciplinary investigations against the signatories. Most university administrations did what they were told, and some universities summarily dismissed those faculty members who signed the peace petition. My university was one of them, and I was fired from my position as the head of the Sociology Department of Nisantasi University in February 2016.

That's how I have found myself in Berlin, at Humboldt University's Diversity and Social Conflict Department as a Philipp Schwartz Fellow – a fellowship awarded to 'Scholars at Risk.' Meanwhile not only academics but also a growing number of journalists, artists, human rights activists and, in fact, anyone who dared to criticize the government's policies in the Kurdish provinces or the rising authoritarianism in Turkey, found themselves at the receiving end of governmental persecution, stigmatization and imprisonment.

Potential refugee status

Since I moved to Germany, I have had many encounters with German and European institutions and the media. On most occasions, I have received direct support and solidarity from colleagues and representatives in various institutions and organizations. Nevertheless there were also quite a number of encounters where I felt that the western gaze required me as a victimized subject of its own choice – a subject who is heard only when she talks about the ordeals she has been put through by her persecutor, namely Erdoğan; a subject who is seen only when she exemplifies, in her very person, the authoritarian straitjacket that Erdoğan has been imposing on Turkey. This was what the western gaze wanted to see and wanted me to show. Quite often I felt as if I were selected as a potential refugee for the sole purpose of voicing/showing what the mainstream western institutions and media wanted to hear/to see. Europe needs me as a victim to assure itself that it is indeed 'the saviour' that it has imagined itself to be.

This feeling returns me to the debates in postcolonial studies over recent decades around the agency of the speaker. Can the non-European speak in her own voice? If she does, can she be heard? What I feel now is that I represent the gendered embodied subject that those debates are centered around; that Europe needs me as a victim to assure itself that it is indeed 'the saviour' that it has imagined itself to be. I am also needed to reconstruct its modern gendered, ethnicized 'secular' values in this new era when the dice are being cast anew.

The role of Turkey in reconstructing Europeanness

The time-honored method of reconstructing western values is through a binary opposition between the secular and civilized West versus fundamentalist and barbaric East. The question is whether the modern mindset shaped by and around binary oppositions between ethnic, gendered, religious, or class identities, can affirm the superiority of Western values over Eastern ones without sounding politically incorrect? In today’s world, from the mouth of an un-hyphenated and mainstream European citizen, an affirmation of the superiority of western values over eastern ones does indeed sound too Islamophobic, too ethnocentric, even racist. It would be, however, a different and politically less incorrect matter if the members of a community of educated intellectuals, journalists, academics, dissidents of all colors coming in from the East and rapidly constituting a new diaspora in the heartlands of Europe – were to voice it.

That’s why the task of boosting European self-confidence as a secular and civilized saviour of humanity is assigned not to the real refugees who run for their lives from the war-torn regions of the world to reach Europe in millions, only to find out that they are unwelcome. Instead, the role of rebuilding that familiar/superior sense of a Europeanness that offers relief to a ‘special’ group of non-European intellectuals, is given to that special community that are relieved. In this sense, I am part of what can be called a group of special refugees, who are chosen by the western gaze as its ideal victims. Moreover, this 'victim-savior' imagery conceals the complex motives of western actors engaged in the war in Syria to pursue their own economic and political agenda. This 'victim-savior' imagery conceals the complex motives of western actors engaged in the war in Syria to pursue their own economic and political agenda.

This, more or less, is what I think was at play in the many interviews I gave and seminars I participated in, after I came to Europe. Readers, listeners and interviewers were more interested in the fact that our freedom of expression was violated by the Turkish government than the content of what we wanted to express to the government freely without interference. Apparently, the fact that we are "western leaning" educated victims and that our persecutor, president Erdoğan, is an authoritarian politician from an Islamicist background are a necessary and sufficient explanation for what is going on in Turkey. However, such binary presentations are always exclusionary and they only serve to cover up what one is simply not interested in seeing.

In our case, what this binary presentation of Turkey’s authoritarian Islamist leader against secular, western-leaning dissidents serves to conceal is the complicity of the secular Turkish nationalists in the Islamist AKP government's violent policies in the Kurdish regions. It also blurs EU's and European governments' own complicity in continuing to support the AKP and Erdoğan even long after he took a manifestly authoritarian turn and, as a result, the human rights situation in Turkey deteriorated further.

Reading Turkey

Reading Turkey through the binary opposition between the West and the East keeps the true dynamics of power of Turkish politics out of the focus of the western gaze. This results in misjudging the character of Erdoğan's power as well as misperceiving the secular-westernist bloc (the Ataturkists or Kemalists) as a monolithic and homogenous group. Yet, Turkish nationalism and the anti-Kurdish sentiments associated with it often serve as a discursive common ground, on which the West, as represented by Ataturk's old secular Turkey, and the East, as represented by Erdogan's new Islamic dictatorship in the making, form uneasy but effective alliances, at various levels. Erdoğan plays the Kurdish card to mobilize the Turkish nationalist sentiments prevalent not only in the Islamic but also secular sections of the society, against the democratic opposition to his dictatorial ambitions.

In the European media these alliances are often treated as uninteresting, if not unimportant small prints which no one has the wish or motivation to read – if, that is, they are covered at all.

In reality, in understanding what is going on in Turkey under Erdoğan, it is crucial to note that the main opposition party representing the western-leaning secular values of Ataturk's Turkey, the CHP (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, Republican People's Party), voted last year with the Islamist AKP to revoke the legislative immunity of the Members of the Parliament which resulted, as predicted, in the eventual imprisonment of 13 deputies of the pro-Kurdish opposition party HDP (Halklarin Demokrasi Partisi, Peoples' Democracy Party), including its two spokespersons. Similarly, after Erdoğan parted company with the Gulenists[1] following the latter group’s corruption allegations against himself and key names in the government in December 2013 he looked for a new partner to run the state bureaucracy and approached the so called 'Ergenekon'[2] group known as defenders of the 'deep state'.

This new realignment is extremely important for the course of Erdoğan’s politics because Ergenekon defenders who are known for their ultranationalist and secularist convictions are today in charge of the security operations in the Kurdish regions of the country where under extended curfews countless cases of human rights violations, including violations of the right to life and to property are taking place without the scrutiny of the Western gaze. These facts are not less important than the ordeals that we, as Academics for Peace, had to go through simply because it was the security operations in the Kurdish regions and the resulting human rights violations that prompted us, the Academics for Peace, to come up with our peace petition in the first place.

Teaching Europeans

In an article published on July 26, 2016 in Al-Jazeera, Hamid Dabashi describes the way that European thinkers selectively fail to hear some sectors of non-Europeans in the following words:

Why should Europeans not be able to read, even when we write in the language they understand? They cannot read because they (as “Europeans,” caught in the snare of an exhausted but self-nostalgic metaphor) are assimilating what they read back into that snare and into what they already know – and are thus incapable of projecting it forward into something they may not know and yet might be able to learn.

I agree with Dabashi that the mainstream of the European media and institutions do suffer from a similar disability in “reading" Turkey. By keeping their focus solely on Erdoğan and his dictatorial ambitions, and by assimilating what they see into what they already know, namely the time-honored binary dichotomy between the secular West and Islamic East, they fail to appreciate how Erdoğan plays the Kurdish card to mobilize the Turkish nationalist sentiments prevalent not only in the Islamic but also secular sections of the society, against the democratic opposition to his dictatorial ambitions.

As a matter of fact, the Turkish state has always been quite agile in using arguments of national security to crush struggles for democratization by leftists, feminists, liberals, LGBTIs and intellectuals: but Erdoğan 's latest attack on HDP has carried this long tradition of authoritarianism to new heights.

A peace too far

HDP is in fact, an alliance of a number of left-wing political movements active mostly in the non-Kurdish western regions of Turkey within the Kurdish political movement. It was formed during the so-called peace process, when the country welcomed a ceasefire and the end of political violence. After a campaign staunchly opposing Erdoğan's dictatorial ambitions and promising a human rights based and pluralistic democracy, HDP succeeded in passing the 10% electoral threshold and getting 13% of votes in the June 7, 2016 elections. As a result, Erdoğan's AKP lost its absolute majority in the parliament. Instead of opting to form a coalition with one of the other political parties in the parliament however, Erdoğan decided to repeat the elections and played a key role in breaking the peace process with the PKK (Partiya Karkeren Kurdistan, The Kurdistan Worker's Party) in a rupture that led to the most recent bout of political violence in Turkey.

Amidst escalating clashes with the PKK in the Kurdish regions of the country, frequent suicide bombings by such terrorist organizations as ISIS, and TAK (a radical splinter group of the PKK) in various urban centers of Turkey which claimed hundreds of life, and an intense defamation campaign stigmatizing HDP as a supporter of terrorism and violence, Erdoğan's AKP managed to froth up fresh anti-Kurdish sentiment in society. When the elections were indeed "renewed" on November 1, 2016 through Erdoğan’s manipulations, the AKP won back its absolute majority in the Parliament, while the HDP votes fell to 11%. The new AKP government launched the security operations mentioned above in the course of which hundreds of civilians were injured or killed, and entire towns were, literally, demolished. Could Erdoğan implement these violent policies in the Kurdish regions, without the active support, or at least, silent complicity of at least some of the secular segments of the society?

Would any of this have happened, if the HDP had not struck a clear, staunchly democratic stance against Erdoğan's dictatorial ambitions, or if the PKK had simply continued to resist responding to Erdoğan's provocations in the Kurdish region? Could Erdoğan implement these violent policies in the Kurdish regions, without the active support, or at least, silent complicity of at least some of the secular segments of the society? The answers to these questions are of key importance for a truthful understanding of what is going on in Turkey.

Europe’s Kurdish issue

Unfortunately, however, neither these questions, nor the cycle of violence which has befallen the Kurdish regions of Turkey since the June 7, 2016 elections has become as visible to the western gaze, as the personal hardships that we, the Academics for Peace, have had to suffer as a result of our call to the Turkish Government, to break that insane cycle of violence.

As an academic active in human rights and feminist circles, I have participated in many advocacy missions at various EU-platforms, as well as in a number of European states in the last decade. And in the last three or four years I have experienced first hand the difficulty that many European human rights activists too have been experiencing, namely the difficulty of getting European officials to take an active interest in the detorioration of the human rights situation in Turkey, particularly in the Kurdish regions of the country.

Turkish and Syrian Kurds try to tear down border fence at Suruc in Sanliurfa province, September, 2014. Tens of thousands of Syrian Kurds fled into Turkey after an onslaught by the jihadist Islamic State (IS) group. Many wanted to return to protect their homes. Depo Photos/Press Association. All rights re-served.But the Kurdish issue is not just limited to Turkey, and taking an active interest in it requires the European mainstream media to follow closely all the actors involved in the war encompassing the whole region. It also requires them to share responsibility for the millions of the real refugees that that war generates. When we think about the European weapons used in that war, as well as the shady refugee deal that was struck with Erdoğan to keep the real victims of that war, namely the Syrian refugees, outside European borders, it is hardly surprising that the readers of the European mainstream media are so reluctant to look in the direction we are trying to point out.

'There is a crack in everything/ That's how the light gets in'

Let me draw to my conclusion. First, the carriers of the western gaze are not only Europeans. As I mentioned earlier, there are also Turkish journalists who want to use the position of a victim with a muted voice. But more importantly, there are also European journalists and institutions who keep a critical distance from the western gaze and position themselves as equals when they come face to face with this “special” group of non-European intellectuals. When they stand in solidarity with the latter, they think not in lieu of them but with them, they respect that special group’s agency and they do not impose predetermined frames, restricting what the members of this special group want to express. “I cannot help thinking that it could be us, who had to go through what you have gone through.”

The words of a German TV documentarist I met epitomizes this mindset: "We are obviously different, you and us" he said to me after an interview, "but there are so many similarities between our everyday lives and our worldviews that I cannot help thinking that it could be us, who had to go through what you have gone through. What difference does this experience make in your lives? What do you think are the visible and invisible reasons of all this? It is very important to hear that from you..." When I asked him why that is so important he answered: "How else can we think of the next step (to remedy these wrongs)?"

This approach of recognizing and respecting the differences and commonalities between one’s own and others' knowledge, of listening and thinking through both and attempting to move forward towards a new thinking and action resonates with what Walter D. Mignolo calls "border thinking." Mignolo develops this concept in conjunction with what Abdelkebir Khatibi's calls "an other thinking." According to Mignolo Khatibi, "an other thinking is a way of thinking without the other... (and) based on spatial confrontations between different concepts of history."[3] For Mignolo, Khatibi's "an other thinking" is possible when local histories and particular power relations are taken into consideration. For him, border thinking not only aims to understand the knowledge from the subaltern point of view but also closes the gap between opposite knowledges. He explains border thinking as:

the moments in which the imaginary world system cracks. Border thinking is still within the imaginary of the modern world system but repressed by the dominance of hermeneutics and epistemology as the keywords controlling the conceptualisation of knowledge.[4]

Thinking through bodies of knowledge presented against one another, together with one another, and doing so critically cracks the world presented by the binaries. It is these cracks that make "an other thinking possible." Instead of watching and attaching meanings to policies, actors and approaches effecting our lives that stay within the framework of the knowledge we know, these cracks allow us to actively intervene in them. Thinking through bodies of knowledge presented against one another, together with one another, and doing so critically cracks the world presented by the binaries.

The European mainstream may well have a tendency to give a muted voice to the members of the new diasporas to preserve modern European values. It may also have the power to make its own knowledge more visible. Yet, there are also European media, European academics and European institutions, who pursue truth through the cracks, who resist being trapped in the triangle of victim - persecutor - saviour. Some of them are already engaged in border thinking, and some of them are open to think with us, and to produce the new with us, when they confront us.

Instead of just categorizing and positioning us, the members of the new diaspora, as ‘others’, they recognize us as human beings with a full voice. They understand what we mean when we say: I am here, I have a voice, I am not your historical constellation. As Leonard Cohen said in Anthem: "There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in" and they are the cracks which allow the light into the western gaze.

Coming soon: a new project to challenge censorship in Turkey. Sign up here.

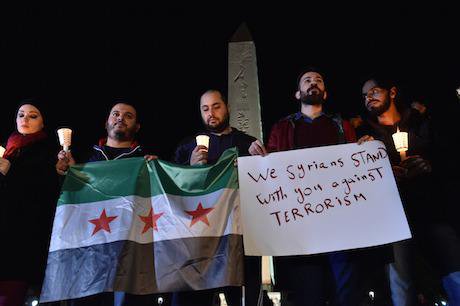

Syrian refugees hold candles, a flag and a placard in solidarity with the victims of a suicide bomb attack in the Sultanahmet district of central Istanbul, Turkey, January, 2016. Peter Kneffel/Press Association. All rights reserved.

An earlier French version of this article will be published in Mouvements (Special Issue, "Turquie autoritaire, Turquie contestataire", Summer 2017).

[1] Gulen movement is a religious and social movement in Turkey with strong transnational ties. Especially after 1980 coup it gained power in state bureaucracy and until late 2013 it had a strong alliance with the AKP governments.After being declared as the culprit of the failed coup of July 15th, 2016 by the AKP government, there has been a huge purge against its members or indeed anyone who is suspected to be a member.

[2] Ergenekon is said to be an extra-legal ultranationalist Gladio-type organization closely associated with what is sometimes called the "deep state." The so-called Ergenekon trials are a group of trials in which hundreds of military officers, journalists and opposition lawmakers were accused of being members of this organization and of plotting a coup against the legitimate government of the Republic of Turkey.

[3] Mignolo, Walter D. (2000) Local Histories / Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges and Border Thinking, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 67.

[4] Mignolo, 2000: 23.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.