While the US government is giving ISPs free rein to track their customers’ Internet usage for purposes of serving personalized advertisements, some Internet users are determined to fill their browsing history with junk so ISPs can’t discover their real browsing habits.

Scripts and browser extensions might be able to fill your Web history with random searches and site visits. But will this actually fool an ISP that scans your Web traffic and shares it with advertising networks?

Electronic Frontier Foundation Senior Staff Technologist Jeremy Gillula is skeptical but hopes he’s wrong. “I'd love to be proven wrong about this,” he told Ars. “I'd want to see solid research showing how well such a noise-creation system works on a large scale before I trust it."

Steve Smith of Cambridge, Massachusetts contacted Ars and Gillula after our recent article about how the US Senate vote to eliminate ISP privacy rules affects users and what Internet users can do to hide their browsing history. He's a subscriber to this browser pollution approach.

“Perhaps more constructively than using a VPN or Tor, fill up your monthly bandwidth allotment with data pollution,” Smith wrote to us. “You’re already paying for the bandwidth, so use it all if your ISP is going to sell your private data. This has the dual benefits of obscuring your actual browsing habits, and, if enough people adopt this practice, discouraging ISPs from selling private data.

"I’ve written a Python class to do this for my household—it crawls for links it finds using random word searches—and have shared the code,” he continued. Smith's code is available on GitHub. Internet users often have to worry about data caps, but Smith set the default rate to use 50GB a month, or about five percent of a 1TB data cap.

Smith’s “ISP Data Pollution” project isn’t the only such effort. For instance, there’s a project called “RuinMyHistory” that opens a popup window that cycles through different websites and a browser plugin called Noiszy designed to “create meaningless Web data” by visiting various websites.

Browsing data sensitive even if surrounded by noise

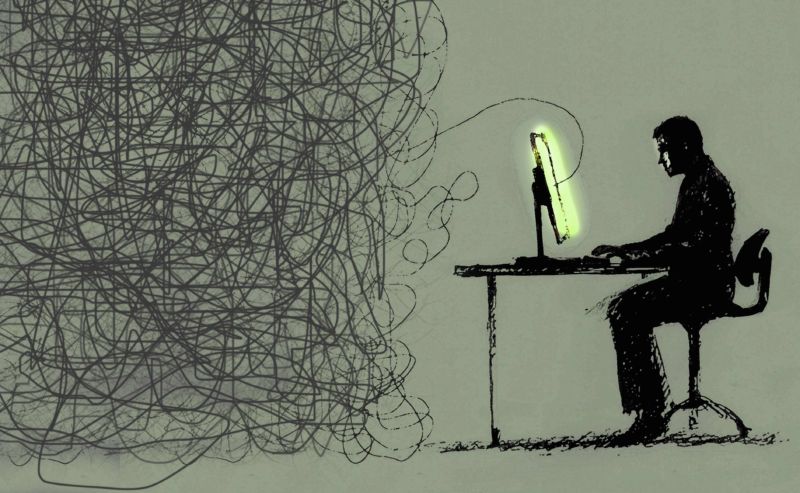

A big challenge for attempts to pollute browsing history is that computers are extremely good at finding patterns, even when the data you want to hide is surrounded by a huge number of random data points. This is the kind of problem that "big data" systems are built to solve.

Gillula believes that data pollution systems may not be sophisticated enough to fool ISPs.

“In the end, it turns into a game of statistical cat-and-mouse between you and your ISP: Can they figure out how to separate the signal from the noise?” Gillula wrote in the e-mail thread with Ars and Smith. “I think ISPs will have a lot more resources (money and smart engineers who will be paid a lot) to try to figure out how to do that—way more resources than any individual or small open source project will.”

Browser noise also doesn’t eliminate the existence of sensitive browsing.

“Some information is sensitive even if it's surrounded by noise,” Gillula wrote. “Imagine if hackers targeted your ISP, your browsing history was leaked, and it showed you visiting specific controversial websites (Democratic websites when you live in a Republican town or vice versa, or maybe looking for a divorce lawyer). Even if that was surrounded by noise, it would be very hard to get the sort of noise that would give you plausible deniability.”

This type of browser pollution system “might work for a bit,” but “if it becomes widespread then ISPs will start throwing resources at solving it,” Gillula wrote.

The Senate vote—which was followed by the House of Representatives taking the same action—eliminates rules that would have required home Internet and mobile broadband providers to get consumers' opt-in consent before using, sharing, or selling their Web browsing history and app usage history. President Donald Trump is expected to sign off on the Senate and House action, killing the rules before they can be implemented.

ISPs want to become bigger players in the online advertising market dominated by companies like Google and Facebook, which face less strict “opt-out” rules than the opt-in rule that would have applied to ISPs.

The idea of browsing history pollution goes back a lot longer than the current debate. Gillula pointed to a 2009 research paper titled “Noise injection for search privacy protection,” which focused on privacy from search engines rather than privacy from ISPs. The ISP Data Pollution project is also similar to an older project that focuses on fooling search engine tracking: a browser extension called TrackMeNot was created years ago for Firefox and Chrome and “periodically issues randomized search-queries to popular search engines, e.g., AOL, Yahoo!, Google, and Bing.” Security expert Bruce Schneier said this browser extension wouldn’t achieve the desired goal back in 2006 for reasons similar to those brought up by Gillula today.

Undermining ISPs’ attempts to violate privacy “just feels good”

Smith agreed with Gillula that creating browser noise “isn’t a full solution, and that counters are possible,” but he remains optimistic that it can be an important tool for preserving user privacy alongside initiatives like HTTPS Everywhere and other privacy-protecting technologies.

“Though it's possible for an ISP to train a machine learning classifier to detect data pollution traffic generated by this initial version, the ISPs have three big technical disadvantages: no customer-specific uncorrupted ‘truth’ data set to train with, our ability to make the random HTTP GET requests indistinguishable from our browsers, and the ease of adding more randomness,” Smith wrote.

Since first contacting us, Smith said he has already “hardened this data pollution code by adding a decent blacklist and using phantomjs to mimic realistic browser traffic.” Even before the current privacy debate, Smith developed a MacOS firewall for blocking trackers, adware, malicious scripts, and other threats.

"Though data pollution isn't a full solution, it can be a highly effective component—one that forces the opponent to devote enormous and likely futile resources to defeat,” Smith wrote. “Plus, however much I hate wasting bandwidth, it just feels good to actively undermine attempts to profit by violating my family's personal information without consent.”

Reader Comments (155)

View comments on forumLoading comments...