Keenan Barazi called home recently with a request many parents of college students hear this time of year: Can I go to Mexico with my friends for spring break?

In Barazi’s case, his mom said no.

Born and raised in Houston, Barazi is a Muslim whose father emigrated from Syria and has been a US citizen for nearly four decades. Barazi’s mom said she couldn’t deal with the fear that her son might be singled out for extra inspection or, worse, detained when he tried to re-enter the United States.

So Barazi, 22, joined the ranks of American Muslims whose ability to travel is restricted not by official Trump administration policy, but because they’re scared of what might happen when they land in US airports.

Even as federal judges block President Donald Trump’s latest executive order, a parallel travel ban is still in effect. This one is self-imposed and even broader than the president’s, eroding the freedom of movement for citizens and non-citizens alike as Muslims decide it’s safer to cancel trips than to risk being held at the border or forced to answer invasive questions before they can go home.

“Just because you’re an American doesn’t mean you can’t be discriminated against.”

That was the calculation of Barazi’s mother, Marguerite O’Connell, who said she felt awful telling her son he shouldn’t join his friends in Puerto Vallarta just because of his name and religion.

“My first instinct was, ‘You’re going to get detained. They’re going to mess with you.’ His first thing was, ‘Mom, they can’t detain me. I’m an American and, besides, I look super white,’” O’Connell said. “It’s very hard on a mom to have to say to her American-born Houston child, ‘Just because you’re an American doesn’t mean you can’t be discriminated against.’”

Muslims who are sitting out foreign travel for now say the court rulings against the executive orders, however heartening, are only temporary and so far haven’t guaranteed smooth passage for all Muslims, whether or not the travelers have roots in the six countries named in Trump’s order.

The fears might sound overblown except that nearly every week, a nightmare airport story involving a US citizen who’s perceived to be Muslim is splashed across social media. Muslims figure that if it’s happened to Olympic medalist Ibtihaj Muhammad, non-Muslim NASA scientist Sidd Bikkannavar, and, on two separate occasions, to Muhammad Ali Jr., what’s to stop immigration officials from questioning them?

Tuktom Albdair, 18, is a high school senior from Dearborn Heights, Michigan, an Arab and Muslim enclave where so many students are dealing with this issue that she started reporting on it for her school paper. She eventually had to turn over the story to another student, since the subject hit so close to home that it became a conflict of interest, she said.

Albdair’s family, all US citizens who were born in Iraq, canceled a trip to Australia, where they’d planned to visit a sick relative and do some sightseeing. Albdair said it stings that her trip was scrapped while her non-Muslim friends are packing for theirs, but she handles it by smiling, wishing her classmates a good time, and working extra hard toward her dream of a career with enough political influence to change what she views as unjust scrutiny of ordinary Muslims.

“At the airport, they’re going to look at me and say, ‘You have an Arabic, foreign name, and you look foreign because you wear a scarf,’” she said. “It’s not a matter of them letting me in — they’ll let me in, I’m an American citizen — but it’s the trouble I have to go through to get back in. It’s not worth my time to spend hours at the airport just to explain, yes, I am an American citizen, yes, I am allowed back in. All of that just to go home.”

fucking terrifying email from my school advising students from Muslim countries not to go home for spring break.… https://t.co/wL2C7CzM7p

Traveling in and out of the country has been an ordeal for Muslims since the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, but immigration attorneys say the current government-backed hostility toward Islam and the erratic interpretation of policies make traveling while Muslim even more of a crapshoot than it already was.

Immigration and border protection agents have wide berth to decide who gets extra inspection upon arrival. They have the right to confiscate cell phones, laptops and other electronics, even from US citizens and permanent residents. Muslim advocacy groups have issued checklists for Muslim travelers, with advice such as deleting all social media apps from devices and carrying the phone number of an attorney.

A 21-year-old Muslim student who’s a senior at Columbia University in New York said his family had decided against traveling to Pakistan during spring break mainly because they didn’t want to risk having their belongings seized. He asked not to be identified by name because he didn’t want his speaking out on a politically sensitive issue to hurt his chances of finding a job after graduation.

“The problem wasn’t that we thought we’d be banned,” said the student, a US citizen. “But it’s just the thought of having stuff confiscated from us, being held in the airport for six hours. We’ve heard stories on social media or on the news about people being held up because either they’re Muslim, they look Muslim, they have a foreign-sounding name. We opted not to travel.”

He said it’s important for US Muslims and their non-Muslim supporters to realize that a court ruling against an executive order doesn’t spell the end of Muslims’ travel problems.

“The legislation doesn’t just have this effect that can be turned off and on by the courts,” he said. “It has far-reaching consequences on the psychological state of Muslim immigrants and citizens.”

Apart from the hassle, American Muslims said, there’s the indignity, the feeling of being a second-class citizen in your country. They acknowledge that the decision to stay home is not ideal and leaves them in sort of a catch-22: avoid the government’s possible restriction on travel by preemptively restricting travel.

“In theory, I can travel, but do I want to risk it and not be able to come back just because someone at the border doesn’t like me?”

Sana Mustafa, 25, came to the United States from Syria through a six-week State Department program in 2013. While she was in the US, Syrian authorities detained her father back home. She applied for political asylum because it had become too dangerous for her to return.

Now Mustafa lives in New York, has a green card through the asylum process, and works as a consultant to nonprofit groups that focus on refugee issues. She should be able to travel abroad with no problem, yet she will not take a gamble by leaving the country right now. She’d thought about applying for overseas jobs — not anymore. She used to look for fellowships and conferences abroad; that’s stopped, too.

“In theory, I can travel, but do I want to risk it and not be able to come back just because someone at the border doesn’t like me?” Mustafa said.

Trump’s efforts to reduce Muslim travel to the United States — and the ensuing repercussions for citizens and visa holders — are only the latest blow to Muslims’ basic right of mobility.

Many Muslims have described the feeling of living in a shrinking world as anti-Muslim hostility seeps into the mainstream, finds political cover, and ends up disrupting ordinary lives. Some women who wear headscarves are skipping the gym or no longer feel comfortable grocery shopping alone for fear of attack. Families will plan weekend getaways only to find that homeowners on sites such as Airbnb won’t rent to them based on their names or appearances.

One school of thought is to push back and travel anyway, with Muslims turning their Caribbean cruises or honeymoons in Paris into small acts of defiance. On the domestic front, several new startups are helping travelers navigate Muslim-friendly territory in the United States, pointing them to halal restaurants and hotels near mosques.

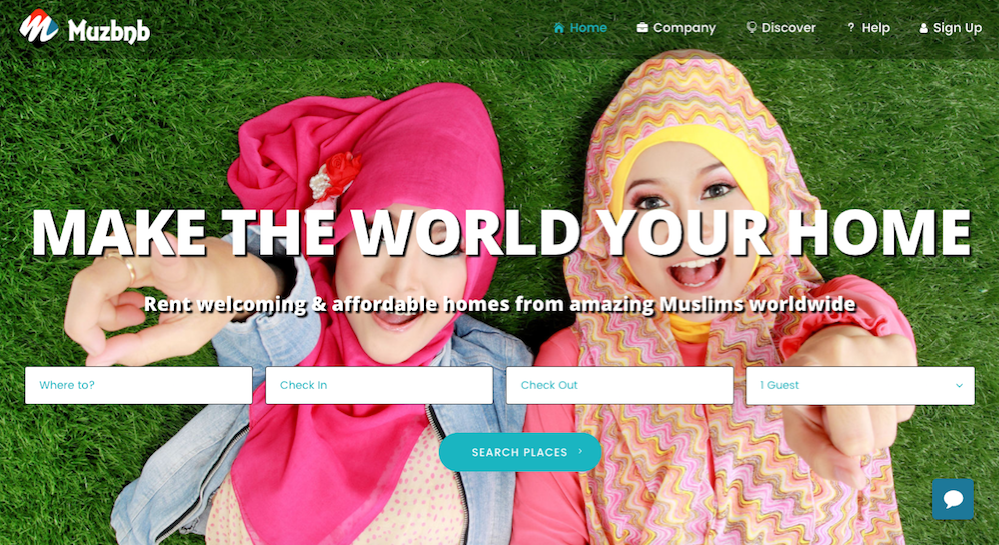

Among the most anticipated is Muzbnb, a Muslim spin on the Airbnb model, but one that makes sure that a Mohamed or a Fatima isn’t turned away when they try to rent a cabin for a ski trip. The site is expected to launch in June, just in time for the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, said Muzbnb CEO Hadi Shakuur, who’s based in Washington.

“It’s ironic that we started a travel company and then the travel ban started, but that’s also part of our intention in doing this, pushing back against some of the vitriol Muslims have been receiving,” Shakuur said. “In the Islamic community, travel and exploration and adventure are part of our tradition and we want to revive that.”

The big test of US-based Muslims’ comfort with traveling abroad will come this summer, during the time of the hajj pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia and the Eid holidays, typically a period of leisure travel as families reunite for feasts and shopping trips.

For now, spring break is showing that Muslims are still thinking hard about whether they should risk leaving, and nerves aren’t likely to settle until a final court ruling on Trump’s orders and a letup in the viral stories about airport drama.

O’Connell, Barazi’s mother, said her son missed out on Mexico but ended up skiing with some friends in Denver, a compromise that eased her heart but not her head.

“Maybe he could’ve gone. But it’s the fear,” she said. “Why do I have to have a conversation with my children about their names? Why does that affect how they’re going to be treated in an airport?”