In the first few weeks of the Trump administration, I reread The Handmaid’s Tale.

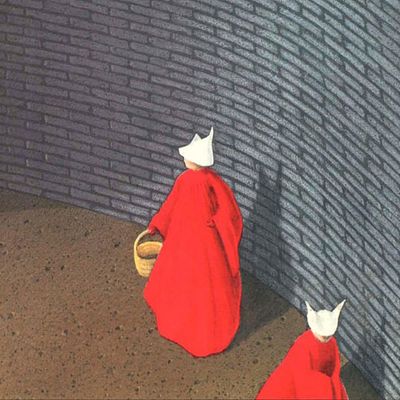

It had been almost exactly 30 years since I’d last visited Margaret Atwood’s fictional feminist dystopia, but I’d been thinking a lot about it. The book, like its authoritarian forerunner 1984, has recently returned to best-seller lists, only in part because a television adaptation is scheduled to air on Hulu in April. It will star Elisabeth Moss in the role of Offred, the heroine whose life, body, husband, daughter, and original name have been stolen from her in the futuristic, religiously ordered Republic of Gilead.

“We never wanted the show to be this relevant,” Moss has said of the television adaptation, which was written, green-lit, and already in production before Donald J. Trump was elected president. Before an Oklahoma lawmaker described women as “hosts” while defending his bill that would require women seeking abortions to gain written permission from the father of the child; before a Texas woman reporting abuse at the hands of her boyfriend was detained by immigration forces in the courtroom reserved for domestic-violence cases; before a report was released showing that violence and threats directed at abortion clinics are at their highest in 20 years; before Mitch McConnell silenced Elizabeth Warren while she read a letter by Coretta Scott King on the Senate floor; before a secretary of Education who has said she sees education as a means “to advance God’s kingdom” was confirmed; and before the First Lady of the United States opened her husband’s rally in Florida with the Lord’s Prayer. And these examples are just from the span of days during which I was rereading the book.

But the decision to bring The Handmaid’s Tale to screen, in advance of our present political circumstances, did not require some sort of mystical clairvoyance. The Handmaid’s Tale was born of, and now has been revivified in, a period of anti-feminist backlash — a response to the gains of women that certainly affected the 2016 election, but which had been playing out long before.

Margaret Atwood, who is Canadian, published The Handmaid’s Tale, set in what we’re to understand was formerly the state of Massachusetts, in 1985. Atwood has said that one of her rules for writing it was that she “couldn’t put anything into the novel that human beings hadn’t actually done” and it is bracing to understand as an adult — as I didn’t, really, on my first read — that everything in the book, from public executions and forced births and separation of mothers from children, to the public shaming and banishment and physical punishment of non-conforming women, has historical roots in America, from slavery to Salem.

The years in which Atwood was writing her book were the ones in which conservative politics had joined forces with religious fundamentalism to elect Ronald Reagan, and the cultural attitudes toward the women’s movement of the late-20th century had chilled into a frozen tundra of anti-feminist sentiment. The messages of the 1980s, many of which would be collected in Susan Faludi’s 1992 book Backlash, were often about the perceived costs of women’s liberation: the dropping birthrate, the miserable and loveless career women, single mothers of color as welfare queens, men under attack.

Women, as they always have, participated in and sometimes led the cultural repudiation of feminism, either as public crusaders in the mode of conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, whose efforts to block the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment had finally succeeded in 1982, or as apathetic eye-rollers eager to differentiate themselves from the now-embarrassing caricature of feminist agitation.

Atwood nods to the merely apathetic in the book: Offred (whose Gileadean name indicates her possession by the “Commander” whose children she’s meant to bear) grew up feeling ambivalent about the radical feminism of her mother, an activist whose face is shown at the handmaids’ reeducation center as an example of an “Unwoman.” Offred recalls how her mother used to tell her, “You’re just a backlash … You young people don’t appreciate things … You don’t know what we had to go through, just to get you where you are.” The unwillingness of the next generation to defend the feminist legacy is part of what led to its undoing.

“There were marches,” recalls Offred of the time of the overthrow of women. “But they were smaller than you might have thought.” She did not attend them. As Mary McCarthy, in her aggressively lukewarm New York Times review of The Handmaid’s Tale, wrote at the time, “We are meant to conclude that such unwillingness, multiplied, may be fatal to a free society.”

McCarthy’s review itself is redolent of backlash sentiment, not unsurprising from a writer whose antipathy toward second-wave feminism (which her 1963 novel The Group, to some small extent, helped to define) was no secret. McCarthy writes that she simply can’t be shocked or frightened by the The Handmaid’s Tale because she feels “no shiver of recognition” reading of a future in which “a standoff will have been achieved vis-a-vis the Russians, and our own country will be ruled by right-wingers and religious fundamentalists, with males restored to the traditional role of warriors and us females to our ‘place.’ … [T]he book just does not tell me what there is in our present mores that I ought to watch out for.”

McCarthy’s inability to find the warning signs of Atwood’s fictional future around her, five years into a Reagan administration, is symptomatic of the attitudes that undergird backlash sentiment: that expansion of rights and opportunity for women are now so established that they are in no realistic danger of rollback. Therefore, those who continue to lodge complaints about the distance still to be traveled can be cast as greedy, whiny, spoilt children.

“American women today are the luckiest, most privileged women in the history of the world,” Phyllis Schlafly told me six weeks before she died, in response to a question I asked her about resurgent interest in passing the ERA. I thought of Schlafly a lot while rereading The Handmaid’s Tale, in part because one of its characters — the barren wife of Offred’s “Commander” — was, in the pre-Gilead United States, an anti-feminist crusader who gave speeches “about the sanctity of the home, about how women should stay home” while leading a public professional life herself, a clear reference to Schlafly. But I also thought of her because she gave me that interview, in which she explained that contemporary women in the United States have every advantage they could ever want, about two hours before Donald Trump accepted his party’s nomination for the presidency, at a Republican National Convention where the fevered calls about his female opponent were “Lock her up!” and “Trump that bitch!”

As it happens, Schlafly’s niece, Suzanne Venker, has this month published a book that argues that contemporary women have become “too much like men … too competitive … too masculine,” and that in women’s personal lives “it’s liberating to be a beta!” Claiming to be a wrong-headed alpha woman during the day, she retrained herself, as Venker’s book details, to approach her husband with practically Gileadean deference “by not arguing with him … by being more service-oriented.”

Venker’s book, like the Hulu adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale, was in the works before the election, and I suspect that it might have had quite a different reception under President Hillary Alpha Rodham. After all, a Clinton presidency would have offered the illusion of female dominance in a world in which the vast majority of political, economic, social, and professional power still remains in the hands of white men. That illusion would have led many of her opponents to unmatched fury at being governed by that woman, and many of her supporters to not notice the degree to which voting and reproductive rights have been eroded in states and cities around the country.

But this is where Margaret Atwood’s prescient mid-’80s nightmare and our current one differ. Because, so far, the marches have not been small. In fact, the Women’s March was the largest one-day political demonstration in the nation’s history. Consider that in 1913, 8,000 women marched on Washington the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration to demand the vote; in 1970, 20,000 women took to the streets to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. On January 21, somewhere between 3.2 and 5.2 million people participated in women’s marches in states and cities around the country. That’s not an increase simply in line with population growth; proportionally, nearly 50 times more Americans demonstrated on behalf of women in January than did in 1970.

The anti-feminist backlash, rather than moving in as a slow tide during a Clinton administration, instead crashed our shores in the form of Donald Trump, making it impossible for anyone not to notice. This cartoonish embodiment of angry white male bias has shocked many awake, and even while it’s true that they were roused too late to make a different choice on Election Day, the wake-up call has provoked a startlingly robust and energetic response among those who not so long ago were too cool for activism.

And while there are limits on the impact of grassroots resistance, no matter how big the marches, it’s also inarguable that the resistance is having an impact: Trump’s first pick for Labor secretary, Andrew Puzder, withdrew in part because charges that he physically assaulted his wife would have made him un-confirmable. Anti-abortion laws are passing in plenty of states, but so is paid-leave legislation. We may have failed to elect a woman president, but women judges have granted stays to Trump’s Muslim ban; women lawyers rushed to airports to help stranded immigrants; young women have led protests; and a woman senator was the only one to vote against all but two of Trump’s cabinet appointees (so far). And recall that even while Donald Trump touts his electoral victory as confirmation that his revanchist movement against progressive inclusivity is a winner, he lost the popular vote by a margin of nearly 3 million votes.

And yet there’s no question that reading about Atwood’s imagined dystopia is far scarier today than it was, I suspect, for adults living in 1985, perhaps in part because the anger at those stubbornly standing in the way of white male dominance is even more intense. In Texas last week, during testimony from a young University of Texas student who is also an intern at NARAL, an anti-abortion legislator became so enraged that he shattered the glass table on which he was pounding his gavel. If Atwood had written such a ridiculously apt metaphor, it wouldn’t have been believable.