Big Ben’s bongs could sound different after tower repairs

The distinctive bongs of Big Ben could be altered after refurbishment, experts have said.

Britain’s best-loved bell will soon fall silent for several months as part of a three year £29 million revamp, to repair the Elizabeth Tower and clock.

Officials have warned that the tower clock is in such a ‘chronic state’ that it may fail if work is not carried out urgently.

But experts at the University of Leicester, who have recently carried out laser vibration mapping to find out how the 13.5 tonne bell produces its characteristic sound, say that renovation work could alter the frequency of soundwaves, and length of the bong.

Removing accumulated soot or making new repairs to the crack in the bell may change its tone, while plans to renovate the structure of the tower, which include refitting the frame which holds the bell, could impact how long the bong travels for.

Big Ben has also never been tuned, so restorers may take the opportunity to make the bell sound closer to what was originally intended, although there are no plans to tune the bell as present. When it was originally fitted by Whitechapel Bell Foundry the clapper was too large, causing a crack to appear and leading to its peculiar dissonant sound. Consequently, it has not rung true since 1859.

Amy Stubbs, General Manager of the Advanced Structural Dynamics Evaluation Centre at Leicester University said: “The sound of Big Ben is entirely unique and made up a number of different frequencies, all of which make it quite easy to identify when you hear it on the news, or the radio. We all know the sound intimately.

“If you make any changes to a bell then that will alter its sound, for example the crack is having an effect on the way it vibrates, which is why is has a dissonant sound, unlike say that of St Paul’s Cathedral.

“It wasn’t tuned, even when it was new, so if they do any tuning or take any metal off then the sound could change. If it’s very dirty they may remove the soot.

“And if they are rebuilding the belfry then that could change the constraint that the bell moves in and so that could potentially have an impact. If you change the pressure of hitting the bell then it will vibrate in a different way, and perhaps change how long it rings for.

“It’s likely to be very small difference in frequencies, maybe just a fraction of a hertz, which could be imperceptible to the human ear.”

The bell already has an unexpectedly high sound for such a large casting, which experts believe was the result of an amateur designing its shape.

It will be the third time that the chime has not rung out over London for 150 years, having previously stopped for nine months of repairs in 1976 and six weeks in 2007.

Restorers want to repair the clock and fix cracks in its water-damaged masonry, cast-iron roof and belfry and the frame which holds the bells.

The refit could see the clock faces stripped of the black and gold paint that was applied in the 1980s to return them to their Victorian appearance, of green and gold paint.

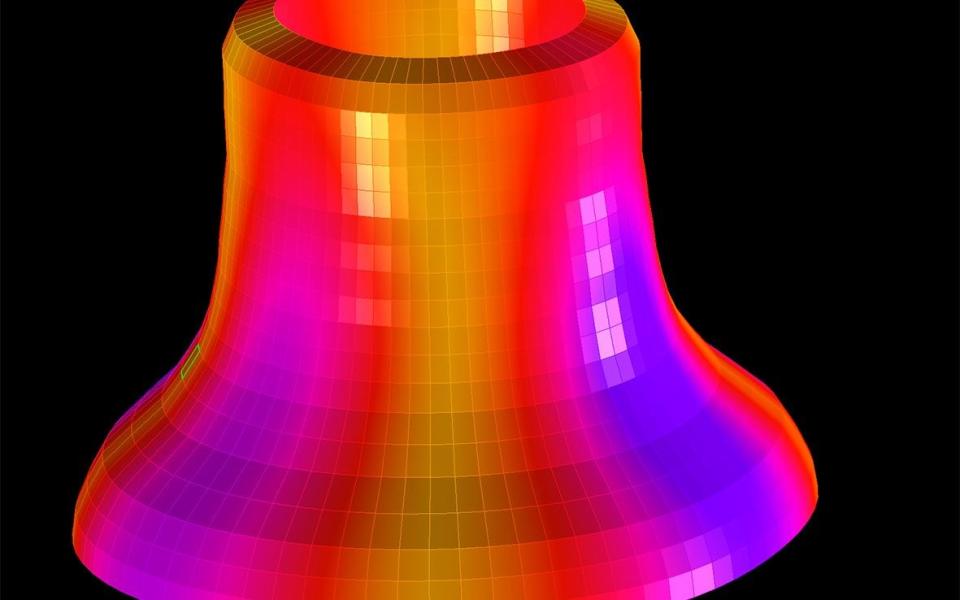

To find out the frequencies which produce Big Ben’s sound, the Leicester team used a measurement technique called ‘laser Doppler vibrometry,’ which involved creating a 3D computer model of the bell and then using lasers to map the vibrations in the metal of the bell as it chimed.

They measured four of Big Ben’s chimes, taking place at 9AM, 10AM, 11AM and 12 noon.

Martin Cockrill, a Technical Specialist from the Department of Engineering at the University of Leicester, who leads ASDEC's measurement team said: “You cannot just glue sensors to a national treasure such as Big Ben. Our ability to do the whole thing quickly without touching the bell was key to the whole project.

“Aside from the technical aspects one of the most challenging parts of the job was carrying all of our equipment up the 334 steps of the spiral staircase to the belfry.

“Then to get everything set up before the first chime, we were literally working against the clock.”

The findings of the mapping project will be revealed during a BBC documentary entitled ‘Sound Waves: The Symphony of Physics’, which will be broadcast at 9:00PM on Thursday 2 March on BBC4 and is hosted by Dr Helen Czerski.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News