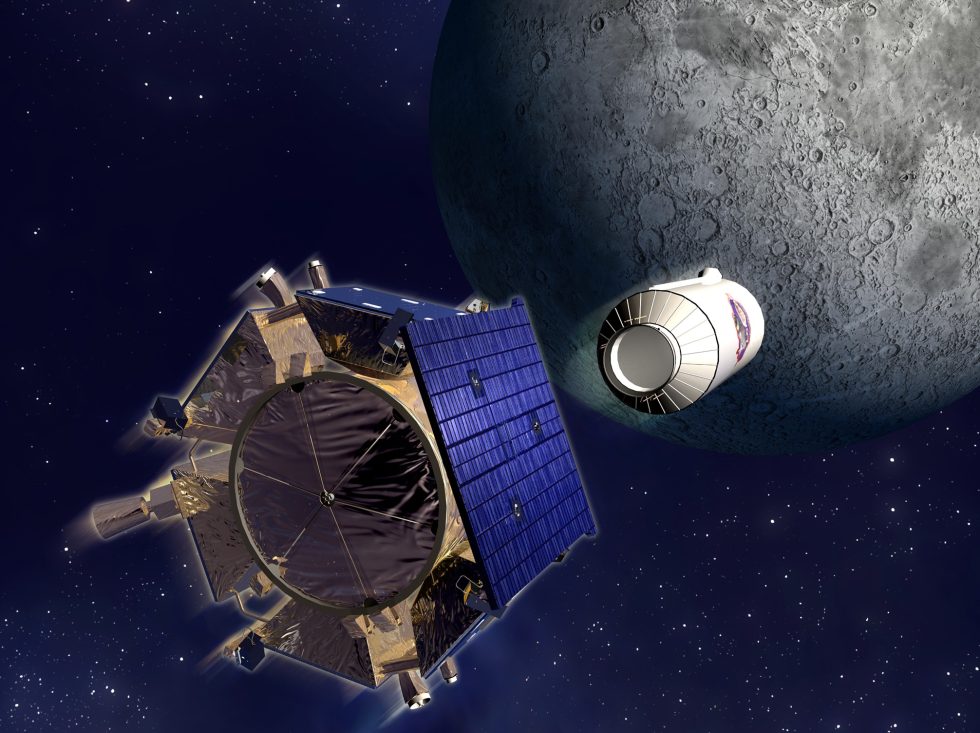

It was time for the spent rocket to die. So the 2,000kg Centaur upper stage, about the size of a yellow school bus, detached from its spacecraft and began falling toward the Moon six years ago. Soon lunar gravity took hold, tugging the Centaur ever faster toward the Moon’s inky black South Pole. An hour after separation, the rocket slammed into terra incognita at 9,000kph (or roughly 5,600mph).

Named for a mythical creature with the upper body of a human and lower body of a horse, the empty Centaur burrowed several meters into a crater that had not seen the Sun’s light for billions of years. The impact kicked a plume of Moon dust as high as 20 km into space. The detached spacecraft followed just minutes later, sampling the plume. “We knew within hours that we had measured something really interesting,” recalled Anthony Colaprete, the mission’s principal investigator.

Interesting indeed. After more than a decade of speculation and intriguing findings, the Centaur had blasted up grains of pure ice. It provided dazzling confirmation that a world once thought entirely barren and desiccated harbors the most valuable commodity for human exploration—water. Yet even as Colaprete and other scientists announced their findings in the fall of 2009, NASA’s lunar program was dying.

The Constellation plan to return humans to the Moon had by then become bloated and fallen desperately behind schedule. Less than four months after the Centaur slammed into the Moon in October 2009, the White House formally canceled Constellation. Ironically, almost from the very moment scientists found a compelling reason to go back, NASA had forsaken the Moon.

Yet the ever-shadowed poles of the Moon, some of the coldest places in the Solar System, are nonetheless some of its hottest frontiers yet again. Since the Centaur impact, a number of US companies started drawing business plans to unlock the Moon’s water ice for everything from powering spacecraft with liquid hydrogen and oxygen to accessing a wealth of rare metals or building a space-based solar power network.

America’s largest rocket company, United Launch Alliance, has noticed. With an eye on its future, the company is doing critical research on storing and transferring hydrogen and oxygen propellants in space. Many European countries, as well as China and Russia, have also made clear their interest. And just last month, the US Congress signaled its approval, too, by legalizing the mining of lunar resources. More than five years after abandoning it, the space industry appears headed for the Moon all over again.

“We’ve been there before”

NASA turned away from the Moon at the very place where America’s Apollo journeys began. In April 2010, President Obama visited Kennedy Space Center in Florida to deliver his single space policy speech. As Buzz Aldrin looked on, Obama said of the Moon, “I just have to say pretty bluntly here, we’ve been there before. Buzz has been there before.”

-

President Barack Obama delivered his only space policy speech at NASA's Kennedy Space Center on Thursday, April 15, 2010. This gallery highlights some of the key figures present at the speech.Bill Ingalls/NASA

-

As the President disembarks from Air Force One, Buzz Aldrin is at the top of the stairs. Obama later referred to Aldrin during his speech.Bill Ingalls/NASA

-

NASA Deputy Administrator Lori Garver shakes hands with the president.Bill Ingalls/NASA

-

President Obama, left, Air Force Col. Lee Rosen, Commander, 45th Launch Group, center, and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk talk during a tour of the commercial rocket processing facility of Space Exploration Technologies, known as SpaceX.Bill Ingalls/NASA

-

Obama and Musk continue their tour of SpaceX facilities at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.Bill Ingalls/NASA

-

The president shakes hands with NASA Administrator Charles Bolden. In an interview this year, Bolden said he never discussed Mars with the president.Bill Ingalls/NASA

-

President Barack Obama delivers his space policy speech at the Operations and Checkout Building at NASA Kennedy Space Center.Bill Ingalls/NASA

-

A wider view of the historic hangar.Bill Ingalls/NASA

With this one line, Obama had transformed the Moon into a taboo subject within the halls of the NASA administration in Washington DC. Instead of the Moon, Obama said, NASA would send astronauts to an asteroid and then, one day, Mars.

Why the policy shift? NASA had just sponsored an influential report by Norman Augustine and others that found its big-rocket Moon program was unaffordable. Additionally, Constellation and its Moon-first ambitions were launched by a Republican president, George W. Bush. Earlier this year, during an interview with NASA Administrator Charles Bolden, Ars asked the four-time astronaut if he had ever spoken with the president about the abrupt policy change. “No,” said Bolden, who was appointed by Obama. “I have never talked to him about that. To me, it’s really not important.”

Since the 2010 speech, NASA has pushed to meet the president’s new goals. Engineers designed plans to visit an asteroid, but that initiative lacked the funds to fly astronauts deep into space. Then engineers planned to grapple a house-sized asteroid and drag it back to the vicinity of the Moon for astronauts to explore it. But even that proved too challenging, so the plan now is to grab a small boulder from an asteroid and bring that back to the Moon. Technically, this meets the president’s goal of “visiting” an asteroid.

As for Mars, yes, the agency says it is going there in the 2030s. This is its “Journey to Mars.” But the agency has yet to outline a clear roadmap for how to do this, nor has it said how much Mars will cost. Critics have said an agency with no plan is going nowhere, and others contend it hasn’t presented Congress with a budget because it doesn’t want to give legislators “sticker shock.”

reader comments

222