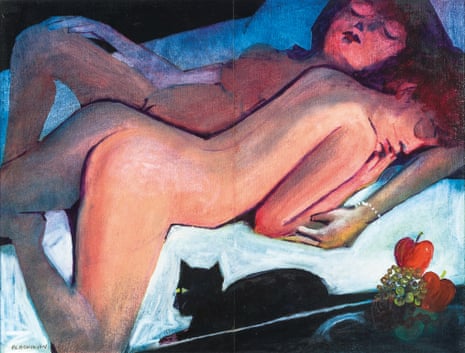

Charles Blackman’s 1980 painting of Women Lovers depicts two women, naked and asleep, serenely sprawled across the canvas. It is Gauguinesque in style, languorous rather than lascivious, more symbolist than sexual. But the mysterious powers-that-be at Facebook this week blocked the image for its “adult content” when it was posted by a Melbourne auction house as an advert for an art sale.

There is no denying that the painting does feature one small smudge of a nipple poking into the air, and a pair of creamy buttocks; and yes, there is a pussy in the picture, but it’s hard to fathom quite what all the fuss is about.

The stupidity of a social media platform that mistakes a painting for pornography doesn’t deserve our righteous indignation, but we should certainly be concerned with what this reveals about the way women’s bodies are being assessed by algorithms. Just as we have got to grips with the dominant “male gaze” that subjects and contorts the female form, we must now contend with the “machine gaze” – more censorious than an overprotective dad and as relentless as the Terminator.

Facebook, to be fair, has not been entirely relentless. Capitulating from its original stance on the image, the company acknowledged that its policy prohibits “photos of actual nude people” but allows for “paintings or sculptures” of nudity. Despite this exemption, things still managed to go tits-up early last year, when the social network deleted an image of Copenhagen’s Little Mermaid statue.

In one respect, this sort of error is easily made by a machine incapable of distinguishing between a statue and a person. But there is something foolish in the exemption made for artworks, as though art were dignified by abstract beauty and separable from basic erotic impulses. When the late John Berger compared two sitters, one “a model for a famous painting by Ingres and the other a model for a photograph in a girlie magazine”, their expressions, he observed, were “remarkably similar”. It doesn’t take an art critic to notice the eroticism of an artwork, but perhaps it takes more than a machine to understand precisely what constitutes “adult content”.

In the meantime, Facebook lumbers on, clumsily censoring images of breast-feeding mums, deleting Pulitzer-prize-winning photographs of the Vietnam war, and omitting illustrations to articles on mammograms. And we, in turn, fulminate over social media filters that are incapable of discerning context, connotation and intention.

That sounds like a lot to expect from an app, but the idea that an algorithm is innocent, unmotivated by malice and absolved of responsibility because it is incapable of human understanding, is also a kind of naivety. The formulas by which Facebook evaluates the adult content of images are not authorless. There is an architect behind every interface.

Wikipedia’s co-founder, Jimmy Wales, concedes that the average wiki-entry editor is typically “a 26-year-old geeky male with a PhD”. Recent Wikipedia initiatives to attract a broader constituency of editors are underwritten by the acknowledgment that content depends on content-makers. But Facebook is a different beast, the wiring beneath its boards shadowy. Who are the web wizards automating the formulas by which Facebook decides what makes an image innocent or improper? This is not to rail at the restrictions that preserve Facebook profiles from a parade of penises, but it is to say that the process by which our bodies are increasingly inspected by machines warrants our own inspection in turn.

How is it that human bodies – particularly women’s bodies – have become data to be filed and catalogued, permitted or prohibited? The two women in Blackman’s portrait sleep undisturbed. But at the base of the torso of one, there are two black brushstrokes, the slightest suggestion of a pudendal cleft. How strange to imagine a machine scanning those lines and assessing them against a data bank of others, similar and dissimilar. The algorithm is learning about us, stratifying our bodies and our sex, mapping out and narrowing down the ways it thinks we exist and are. So when will we click the “dislike” button?